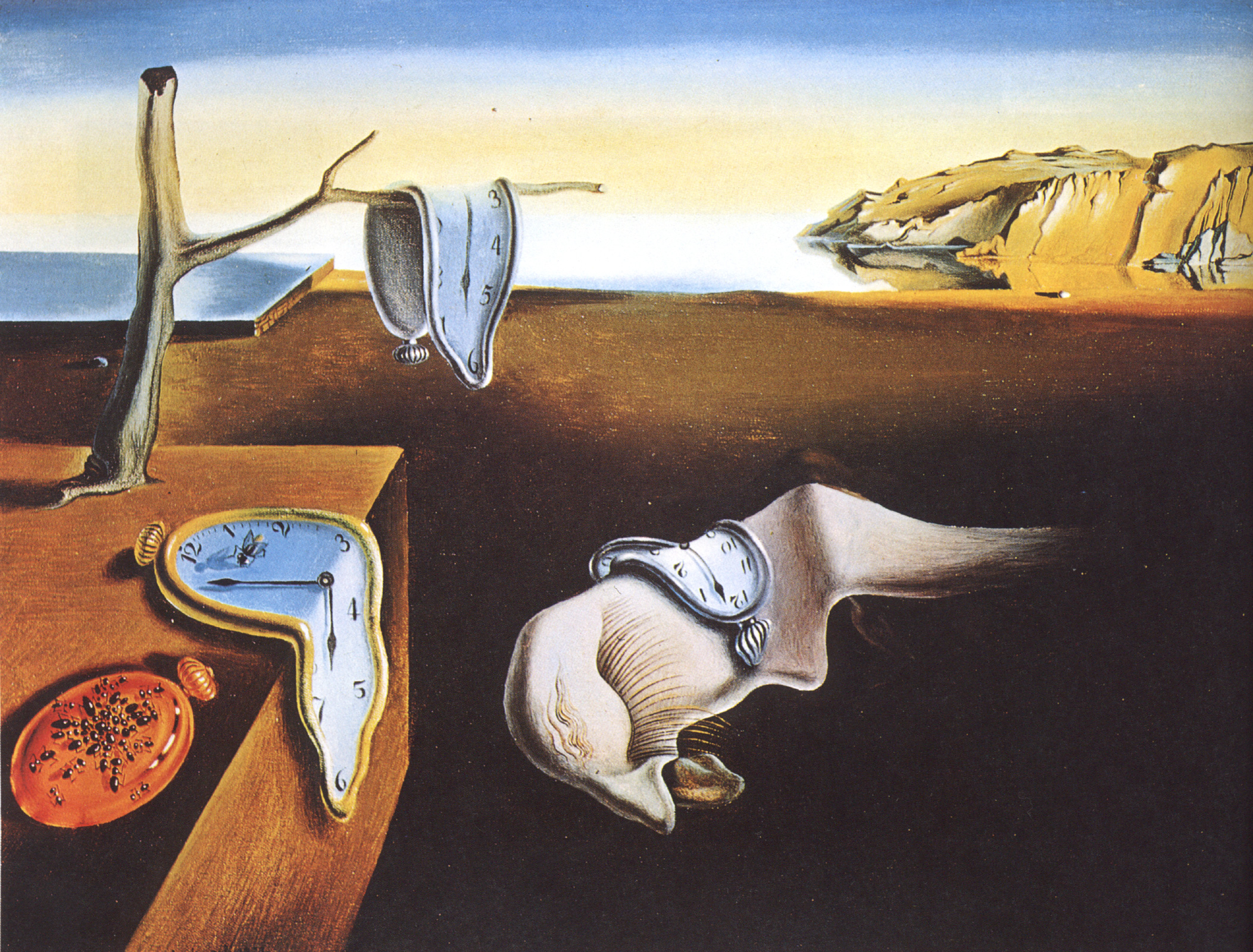

When the names of French poet Paul Éluard and German artist Max Ernst arise, one subject always follows: that of their years-long ménage à trois — or rather, “marriage à trois,” as a New York Times article by Annette Grant once put it. It started in 1921, Grant writes, when the Surrealist movement’s co-founder André Breton put on an exhibition for Ernst in Paris. “Éluard and his Russian wife, Gala, were fascinated by the show and arranged to meet Ernst in the Austrian Alps and later in Germany. Ernst, Éluard and Gala quickly became inseparable. The artist and the poet started a lifelong series of collaborations on books even as Ernst and Gala started an affair.”

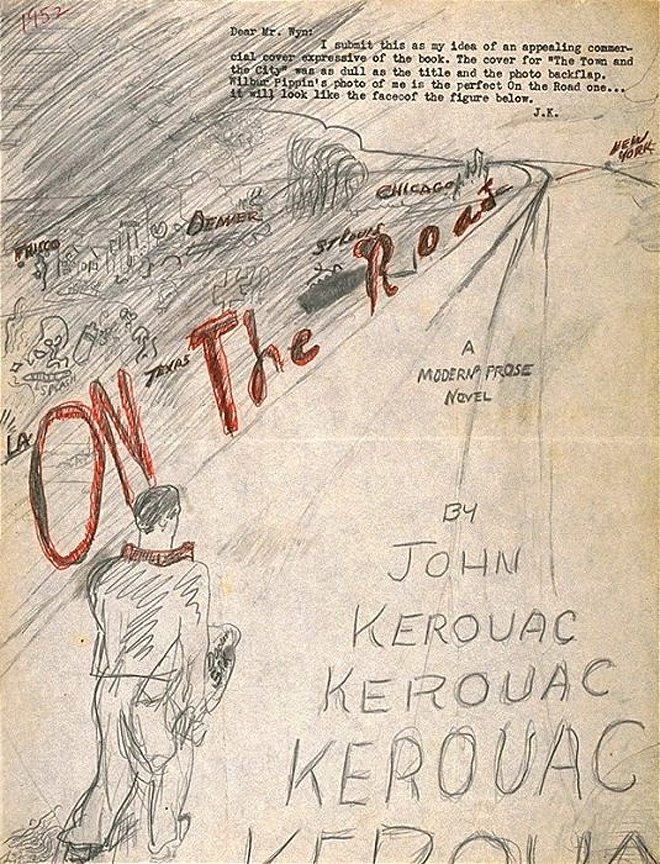

This arrangement “eventually propelled the trio on a journey from Cologne to Paris to Saigon,” which constitutes quite a story in its own right. But on pure artistic value, no result of the encounter between Éluard and Ernst has remained as fascinating as Les Malheurs des immortels, the book on which they collaborated in 1922.

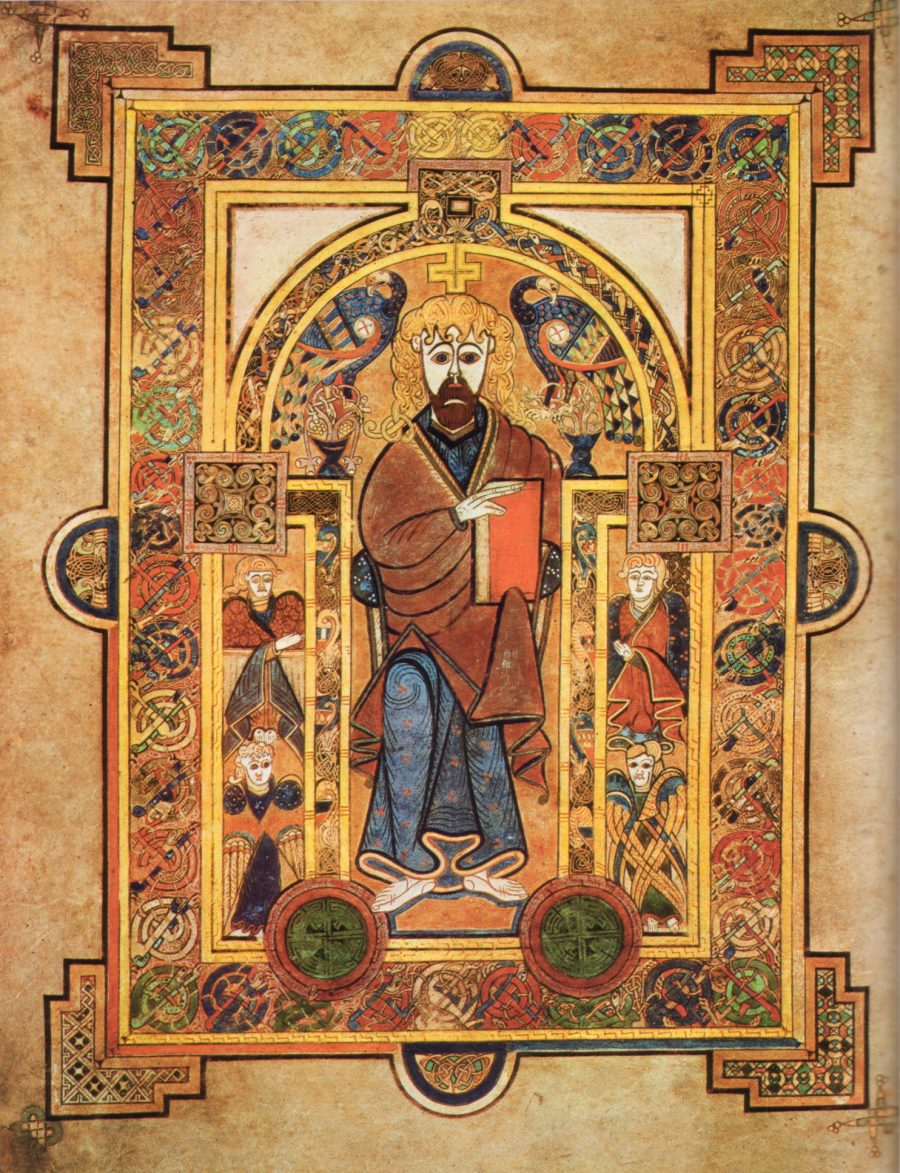

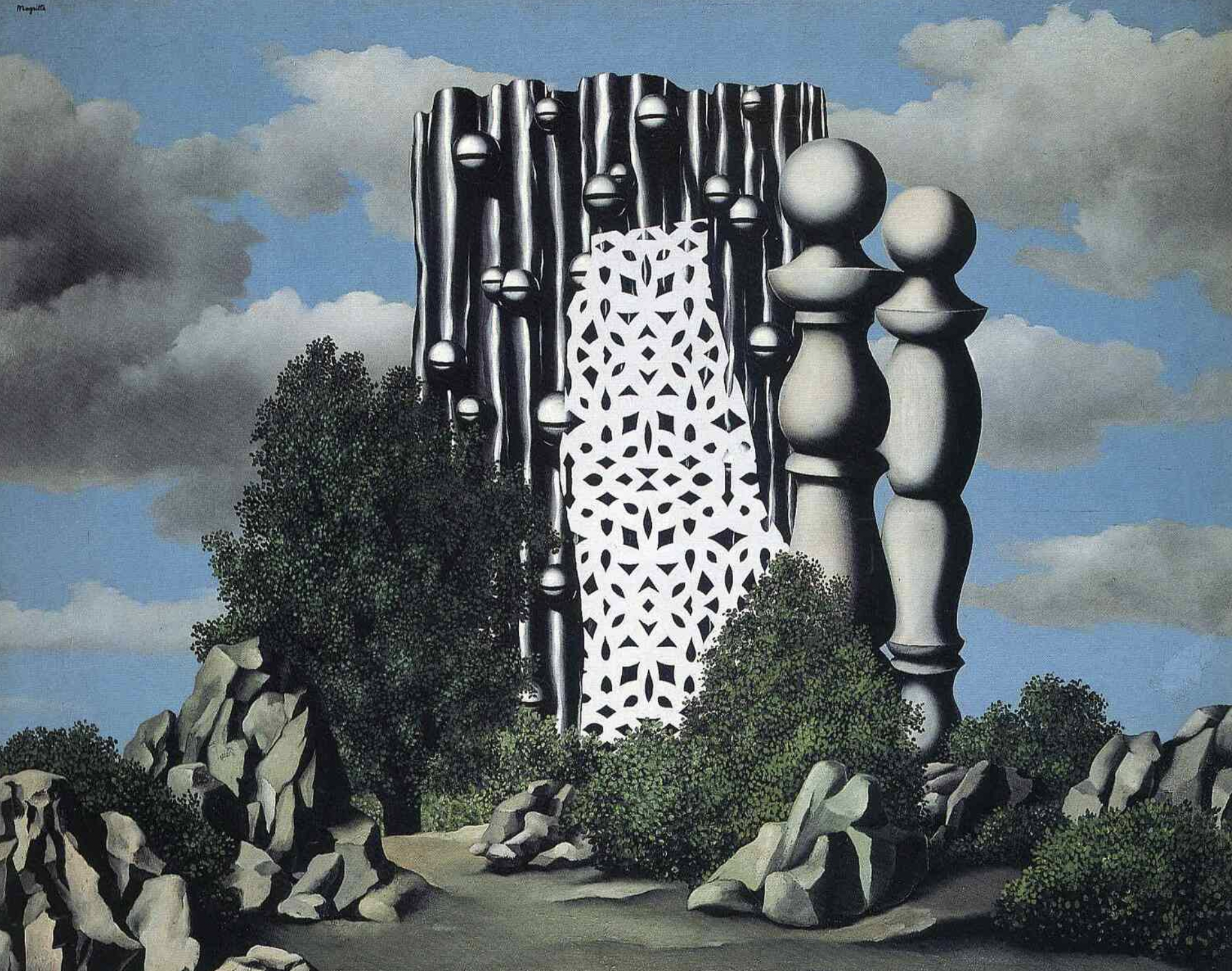

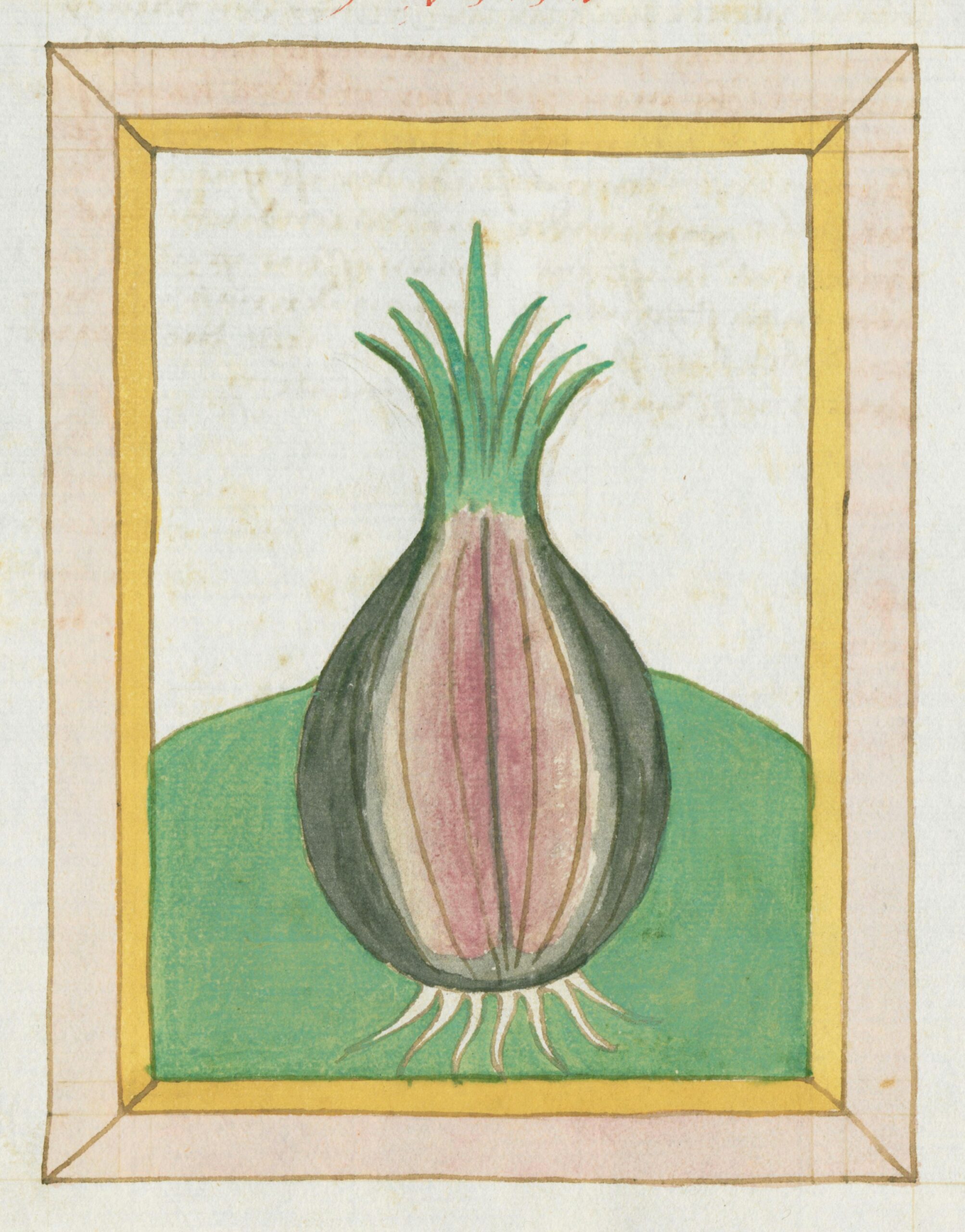

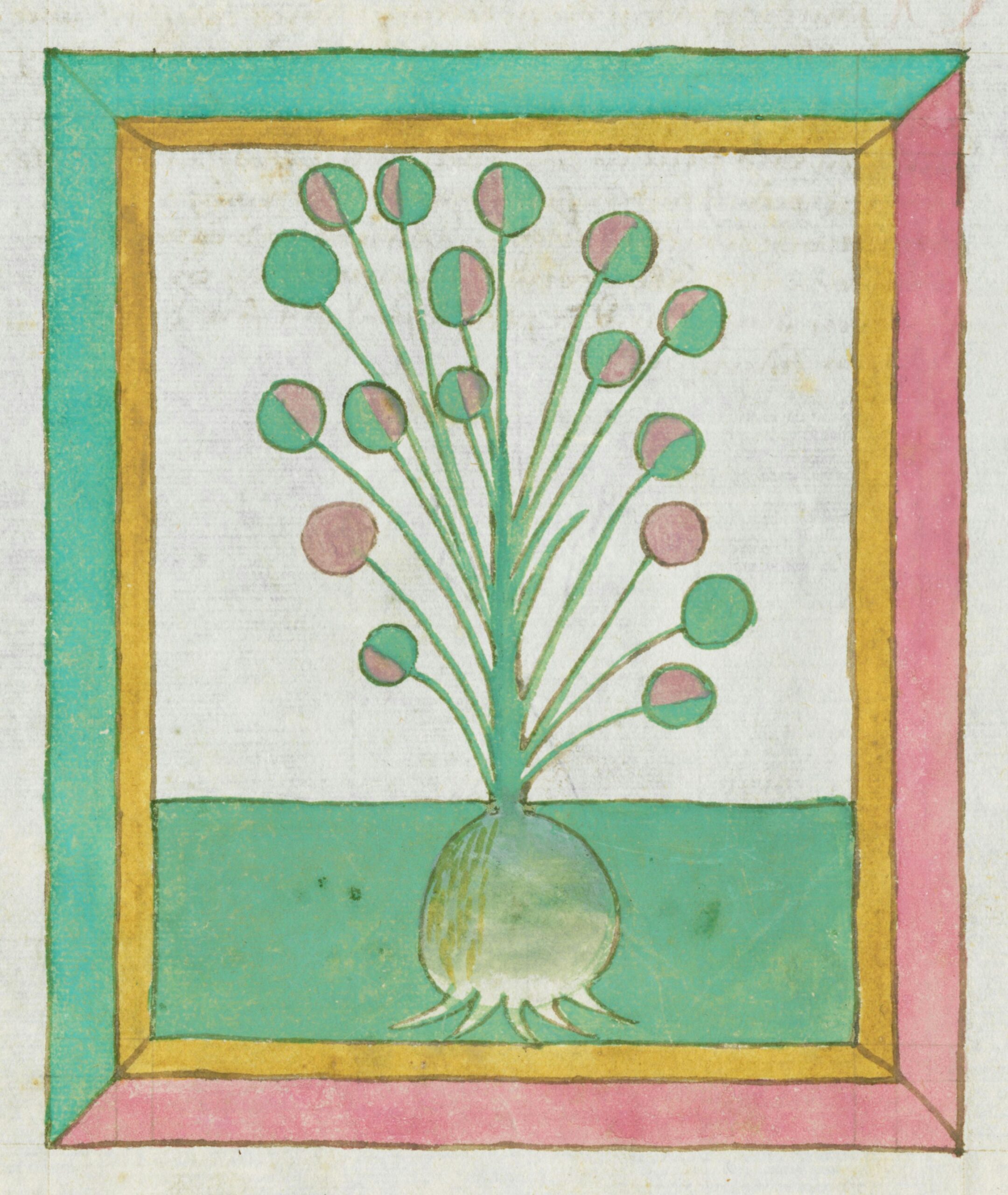

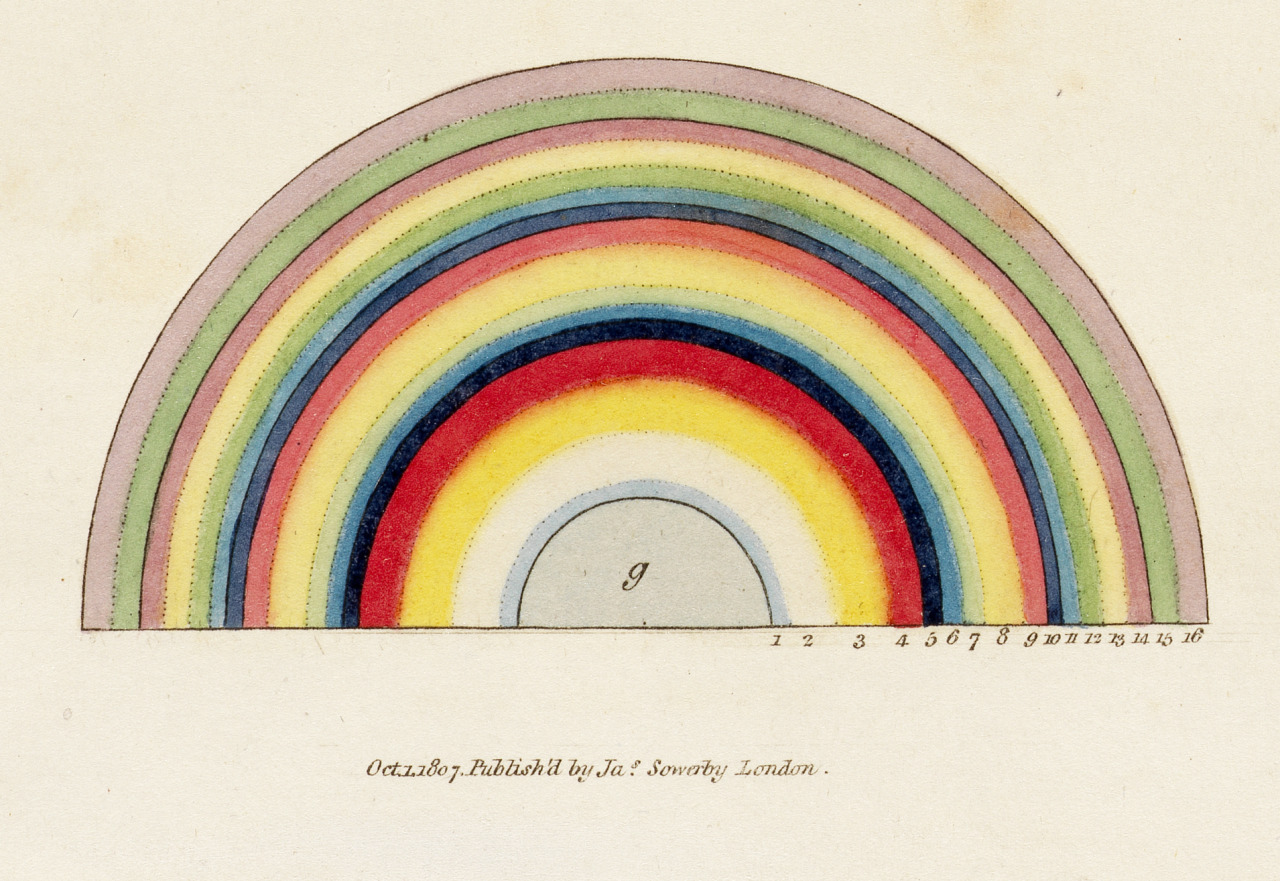

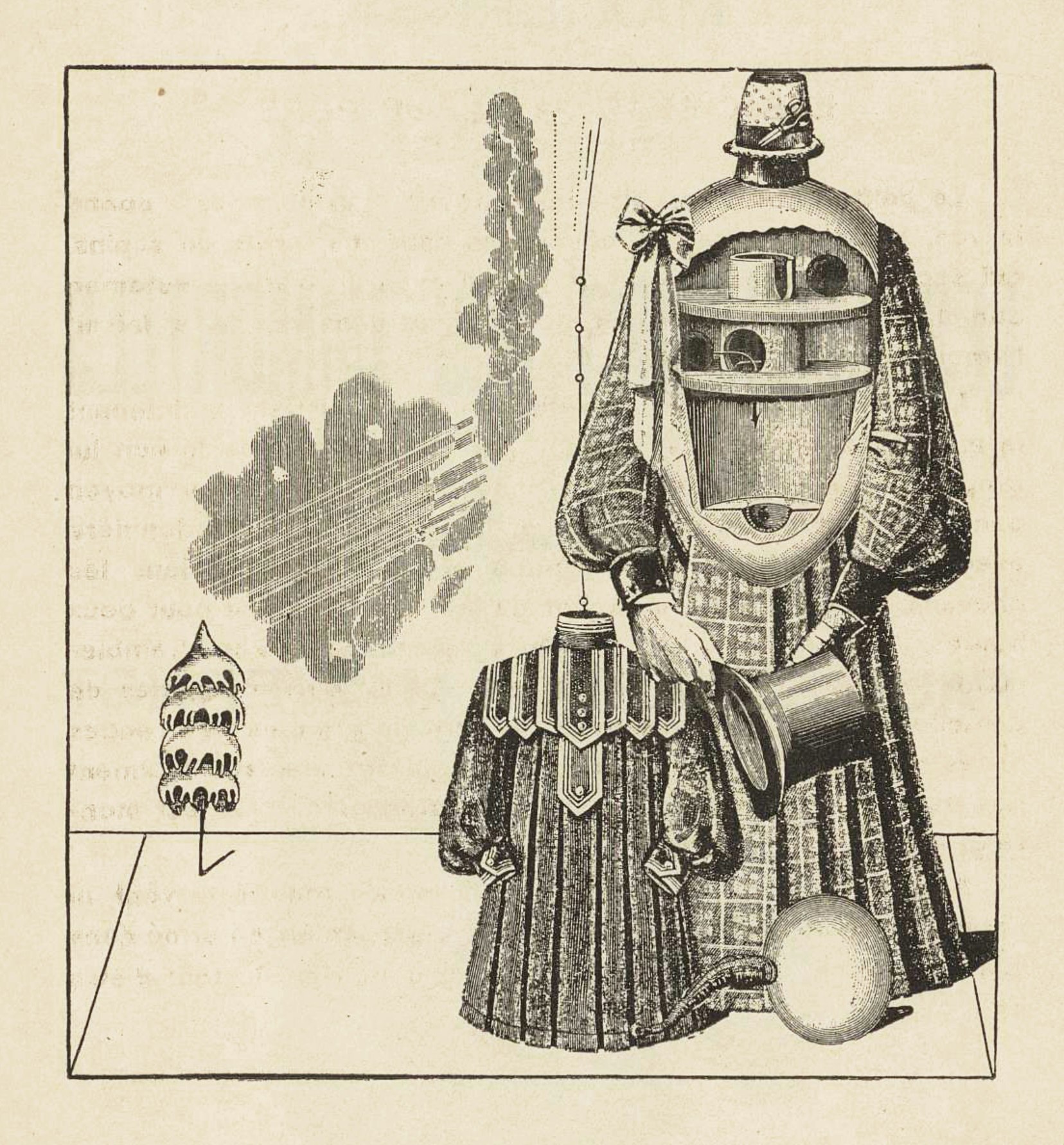

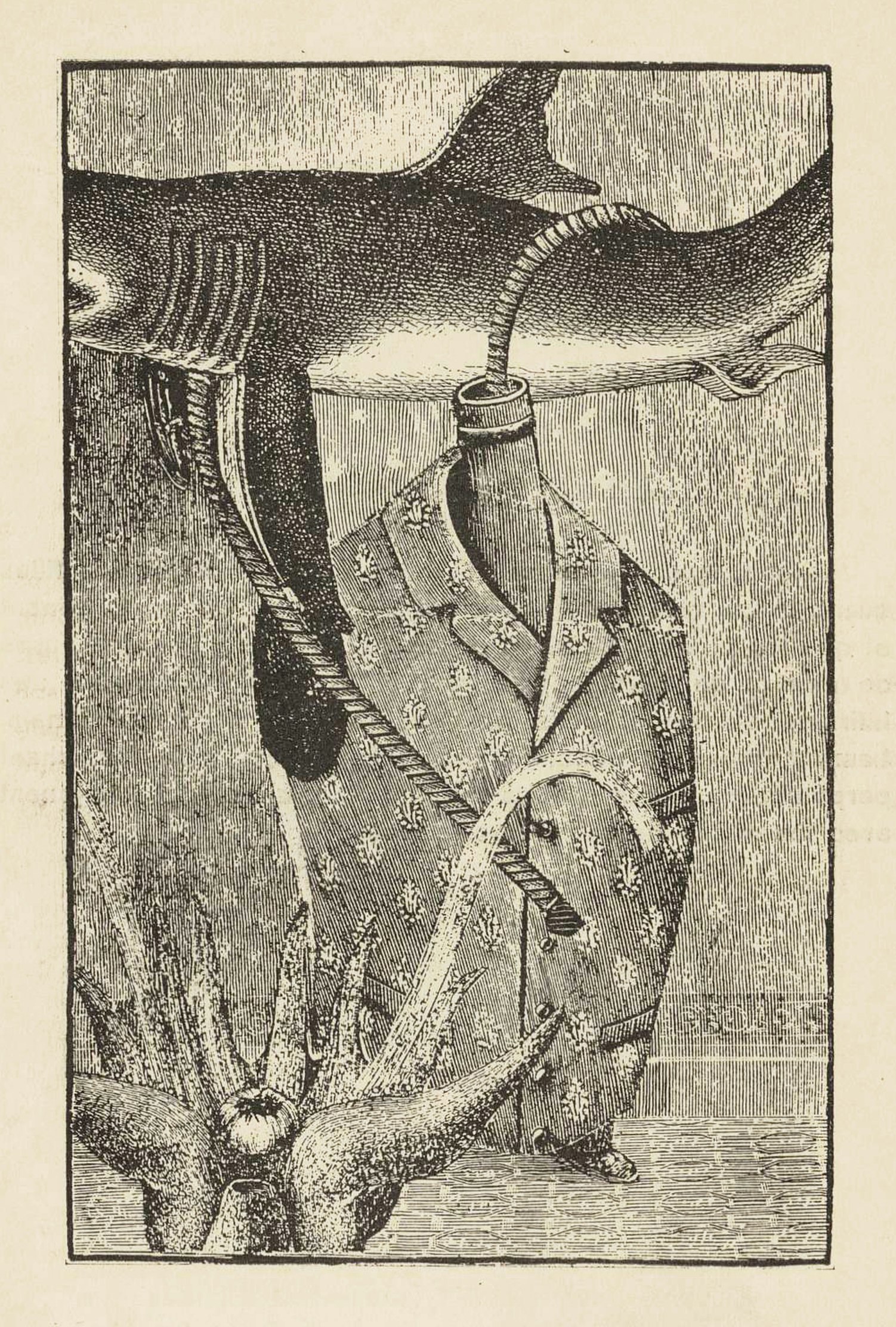

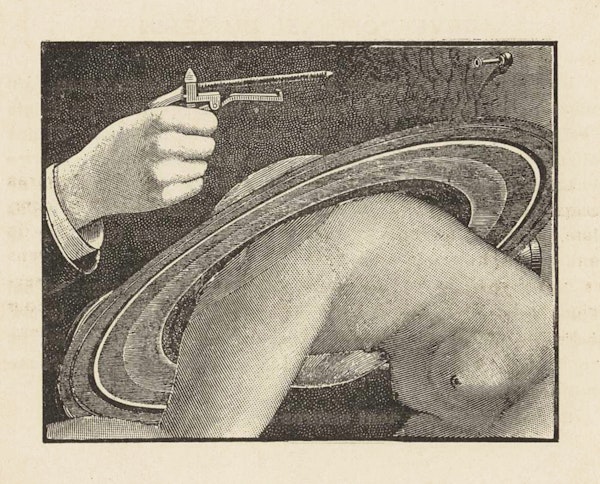

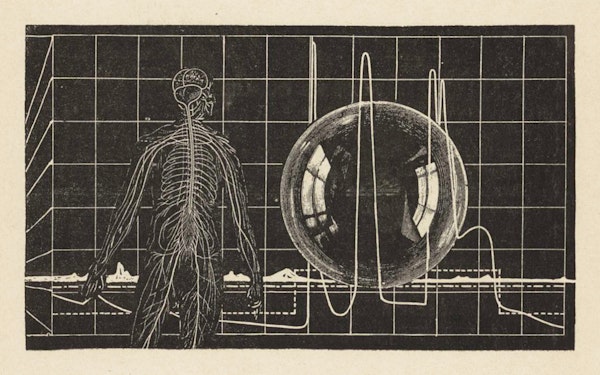

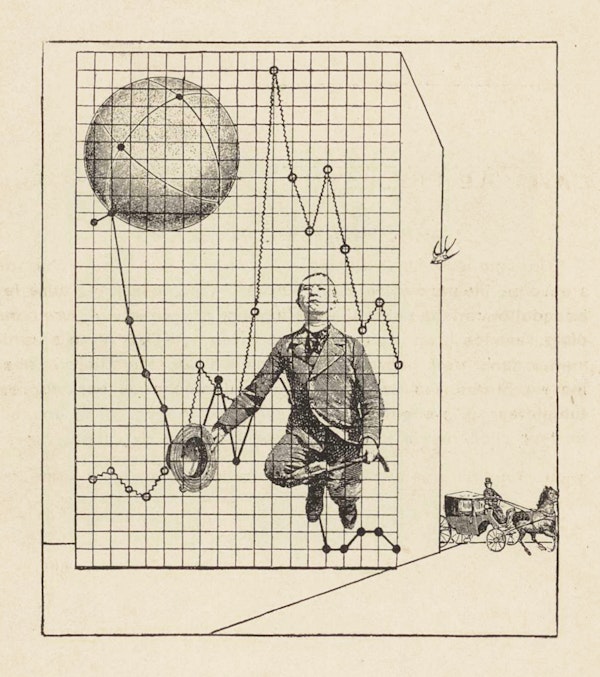

“It appears that Ernst, still in Germany at that stage, created the images first: twenty-one collages composed of engravings cut out of nineteenth-century magazines and catalogues,” writes Daisy Sainsbury at The Public Domain Review. Unlike in the Dada works known at the time, “the artist is careful to disguise the images’ composite nature. He blends each section into a seamless, coherent whole.”

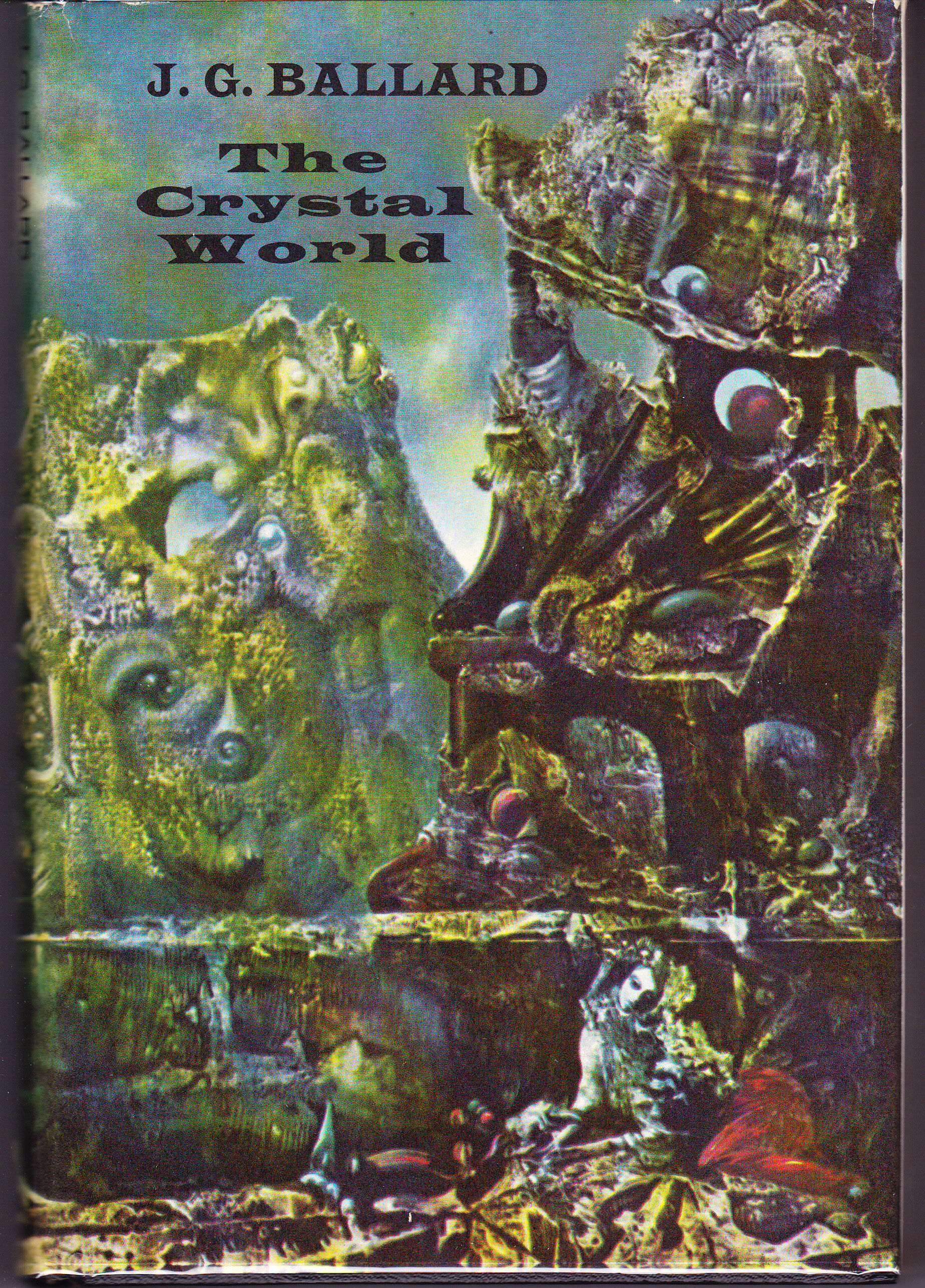

“Ernst and Éluard then worked together on twenty prose poems to accompany the illustrations, sending fragments of text to each other to revise or supplement.” The result, which predates by two years Breton’s Manifeste du surréalisme, “represents a proto-Surrealist experiment par excellence.” In the text, phrases like “Le petit est malade, le petit va mourir” recall “children’s nursery rhymes, with a sing-song quality stripped of sense”; in the images, “a caged bird, an upturned crocodile, and a webbed foot transformed through collage into the ultimate symbol of human frivolity, a fan, evoke the classification systems of modern science (and religion before that) as well as their potential misuse in human hands.”

It’s worth putting all this in its historical context, a Europe after the First World War in which modern life no longer made quite as much sense as it once seemed. The often-inexplicable responses of cultural figures involved in movements like Surrealism — in their work or in their lives — were attempts at hitting the reset button, to use an anachronistic metaphor. Not that, a century later, humanity has made much progress in coming to grips with our place in a world of rapidly evolving technology and large-scale geopolitics. Or at least we might feel that way while reading Les Malheurs des immortels, available online at the Internet Archive and the University of Iowa’s digital Dada collection, and regarding these textual-visual constructions as deeply strange as anything designed by our artificial-intelligence engines today.

Related Content:

An Introduction to Surrealism: The Big Aesthetic Ideas Presented in Three Videos

A Brief, Visual Introduction to Surrealism: A Primer by Doctor Who Star Peter Capaldi

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.