Once upon a time, books served as the de facto refuge of the “physically weak” child. For animation legend, Hayao Miyazaki, above, they offered an escape from the grimmer realities of post-World War II Japan.

Many of the 50 favorites he selected for a 2010 exhibition honoring publisher Iwanami Shoten’s “Boy’s Books” series are time-tested Western classics.

Loners and orphans–The Little Prince, The Secret Garden–figure prominently, as do talking animals (The Wind in the Willows, Winnie-the-Pooh, The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle).

And while it may be a commonly-held publishing belief that boys won’t read stories about girls, the young Miyazaki seemed to have no such bias, ranking Heidi and Laura Ingalls Wilder right alongside Tom Sawyer and Treasure Island’s pirates.

Several of the titles that made the cut were ones he could only have encountered as a grown up, including 1967’s From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler and When Marnie Was There, the latter eventually serving as source material for a Studio Ghibli movie, as did Miyazaki’s top pick, Mary Norton’s The Borrowers.

We invite you to take a nostalgic stroll through Miyazaki’s best-loved children’s books. Readers, how many have you read?

Hayao Miyazaki’s Top 50 Children’s Books

- The Borrowers — Mary Norton

- The Little Prince — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

- Children of Noisy Village — Astrid Lindgren

- When Marnie Was There — Joan G. Robinson

- Swallows and Amazons — Arthur Ransome

- The Flying Classroom — Erich Kästner

- There Were Five of Us — Karel Poláček

- What the Neighbours Did, and Other Stories — Ann Philippa Pearce

- Hans Brinker, or The Silver Skates — Mary Mapes Dodge

- The Secret Garden — Frances Hodgson Burnett

- Eagle of The Ninth — Rosemary Sutcliff

- The Treasure of the Nibelungs — Gustav Schalk

- The Three Musketeers — Alexandre Dumas, père

- A Wizard of Earthsea — Ursula K. Le Guin

- Les Princes du Vent — Michel-Aime Baudouy

- The Flambards Series — K. M. Peyton

- Souvenirs entomologiques — Jean Henri Fabre

- The Long Winter — Laura Ingalls Wilder

- A Norwegian Farm — Marie Hamsun

- Heidi — Johanna Spyri

- The Adventures of Tom Sawyer — Mark Twain

- Little Lord Fauntleroy — Frances Hodgson Burnett

- Tistou of the Green Thumbs — Maurice Druon

- The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes — Arthur Conan Doyle

- From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler — E. L. Konigsburg

- The Otterbury Incident — Cecil Day-Lewis

- Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland — Lewis Carroll

- The Little Bookroom — Eleanor Farjeon

- The Forest is Alive or Twelve Months — Samuil Yakovlevich Marshak

- The Restaurant of Many Orders — Kenji Miyazawa

- Winnie-the-Pooh — A. A. Milne

- Nihon Ryōiki – Kyokai

- Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio — Pu Songling

- Nine Fairy Tales: And One More Thrown in For Good Measure — Karel Čapek

- The Man Who Has Planted Welsh Onions — Kim So-un

- Robinson Crusoe — Daniel Defoe

- The Hobbit — J. R. R. Tolkien

- Journey to the West — Wu Cheng’en

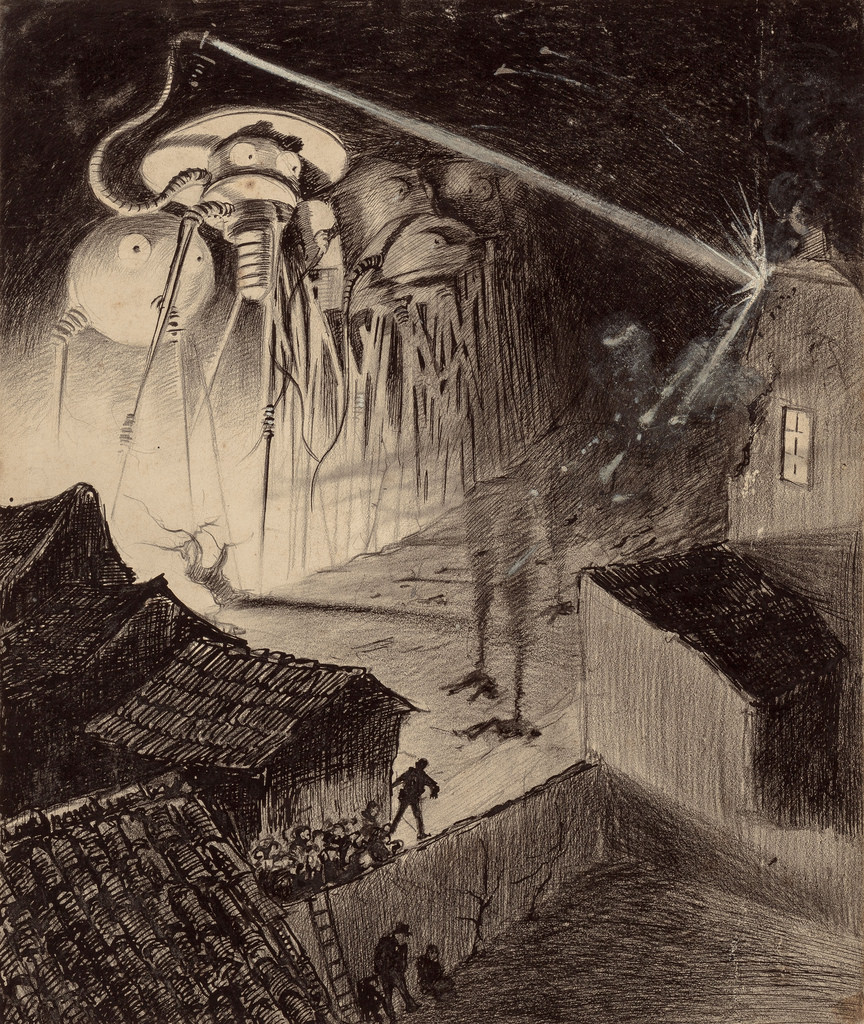

- Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea — Jules Verne

- The Adventures of the Little Onion — Gianni Rodari

- Treasure Island — Robert Louis Stevenson

- The Ship that Flew — Hilda Winifred Lewis

- The Wind in the Willows — Kenneth Grahame

- The Little Humpbacked Horse — Pyotr Pavlovich Yershov (Ershoff)

- The Little White Horse — Elizabeth Goudge

- The Rose and the Ring — William Makepeace Thackeray

- The Radium Woman — Eleanor Doorly

- City Neighbor, The Story of Jane Addams — Clara Ingram Judson

- Ivan the Fool — Leo Tolstoy

- The Voyages of Doctor Dolittle — Hugh Lofting

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Enter an Archive of 7,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized & Free to Read Online

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She’ll be appearing onstage in New York City this June as one of the clowns in Paul David Young’s Faust 3. Follow her @AyunHalliday.