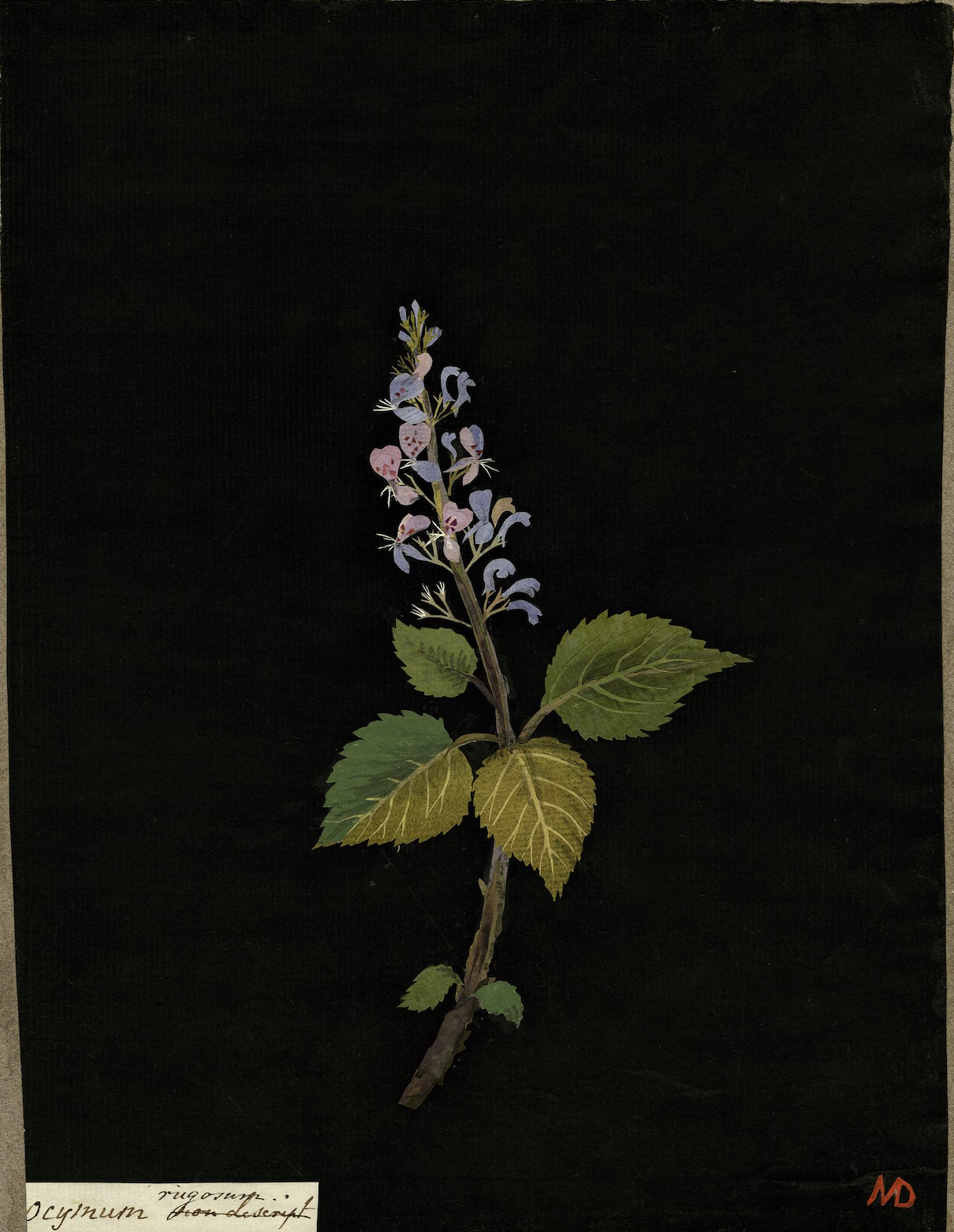

A picture is worth 1000 words, especially when you are a late-19th or early-20th century horticulturist eager to protect intellectual property rights to newly cultivated varieties of fruit.

Or an artistically gifted woman of the same era, looking for a steady, respectable source of income.

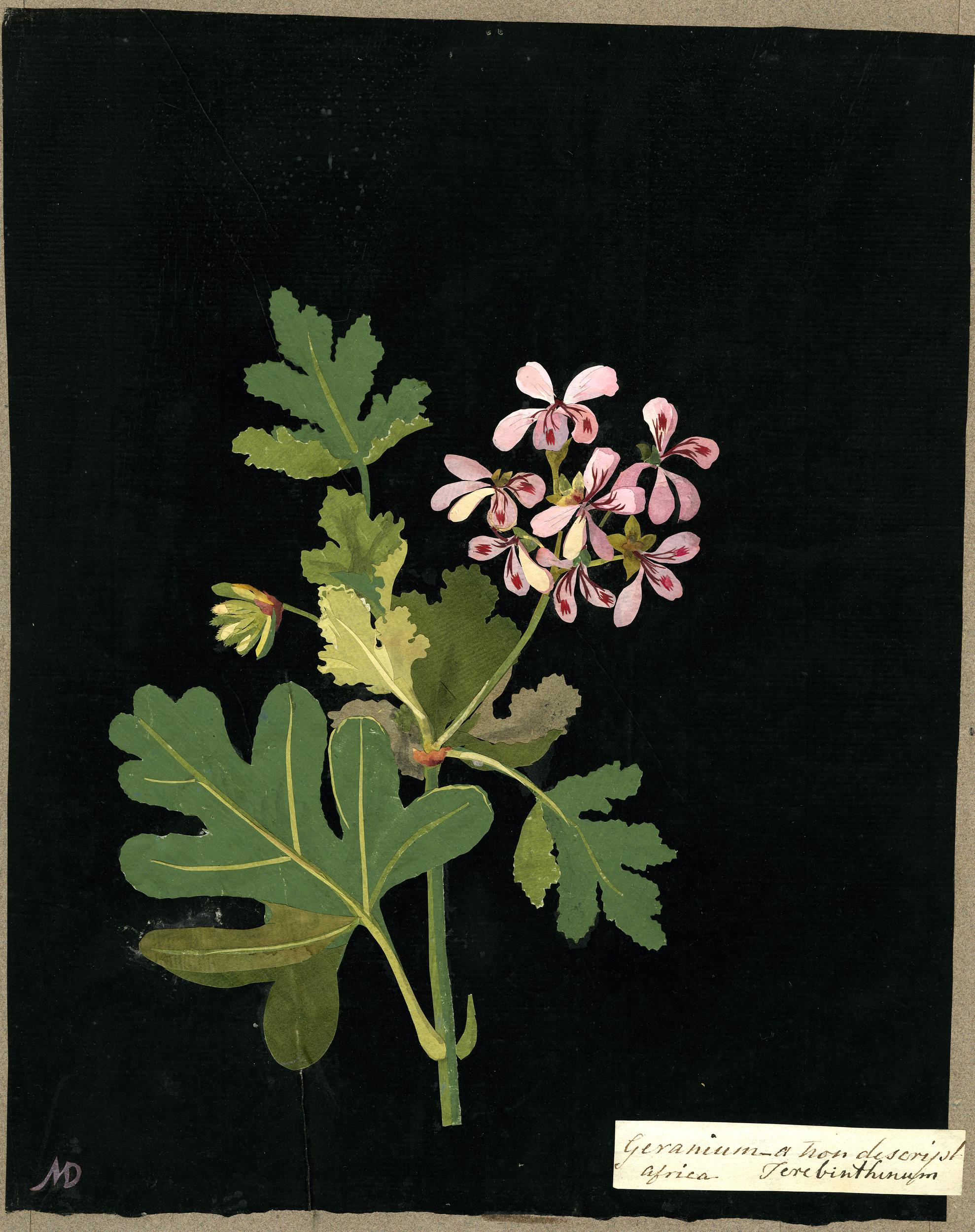

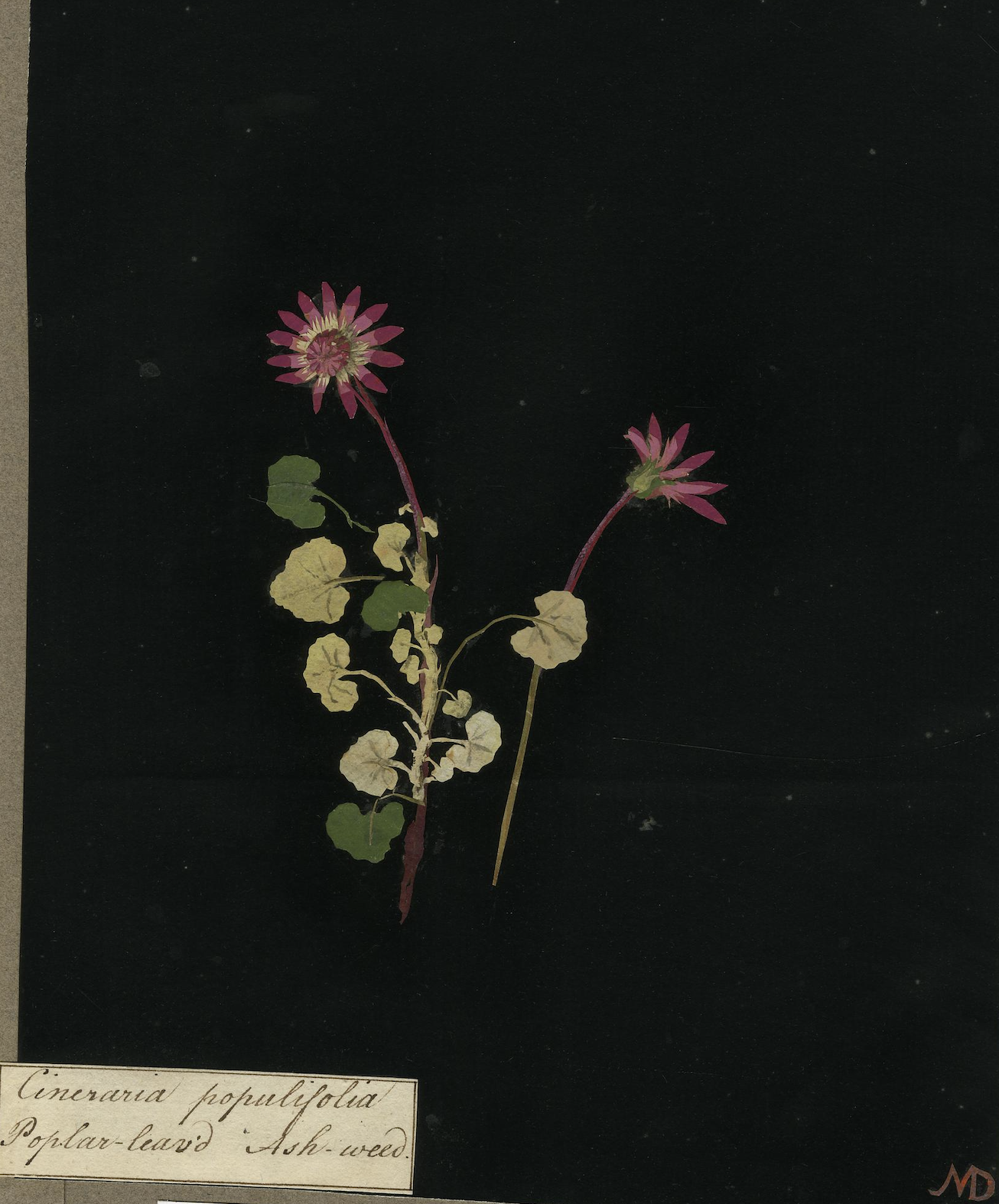

In 1886, long before color photography was a viable option, the US Department of Agriculture engaged approximately 21, mostly female illustrators to create realistic renderings of hundreds of fruit varieties for lithographic reproduction in USDA articles, reports, and bulletins.

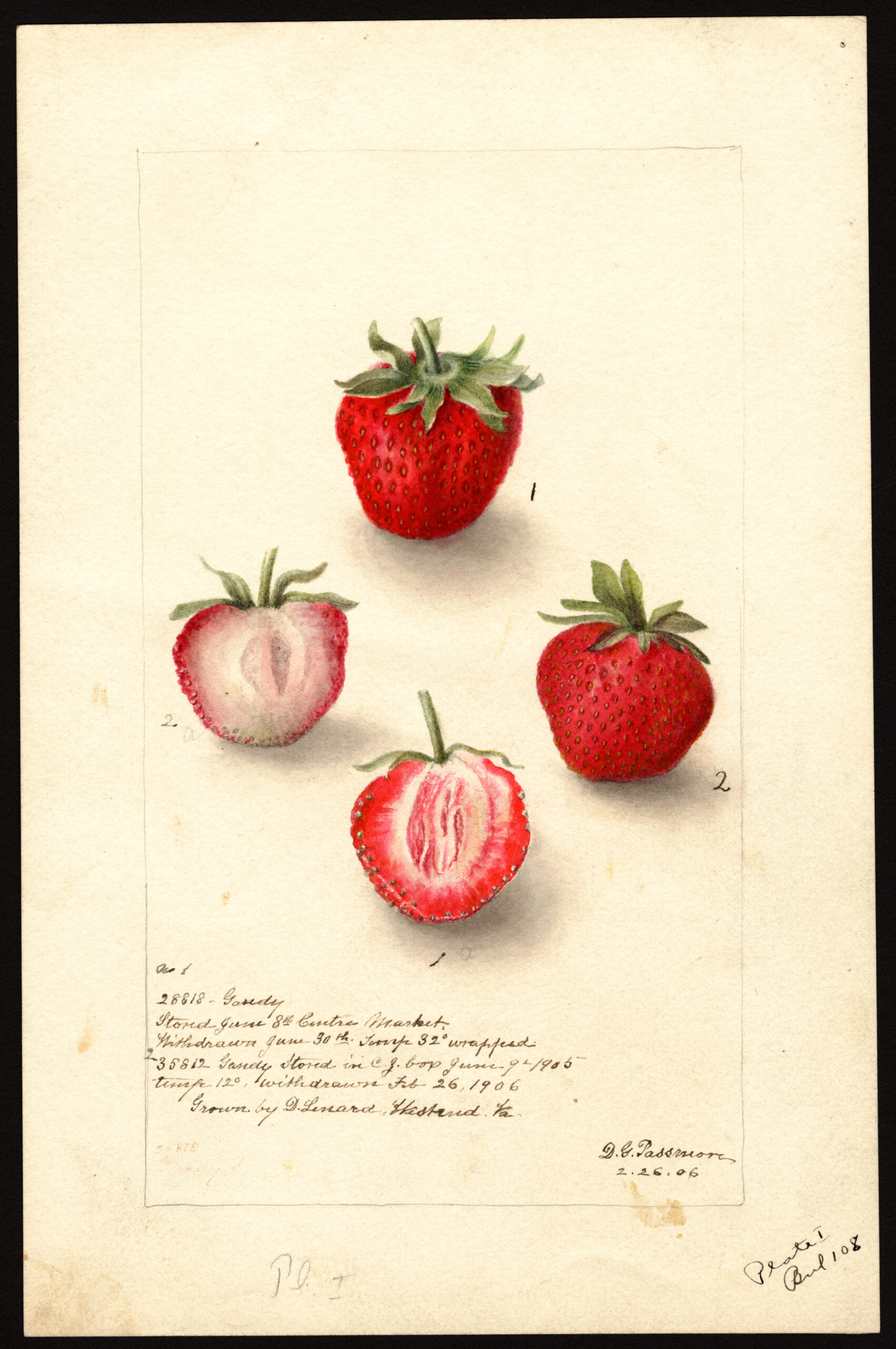

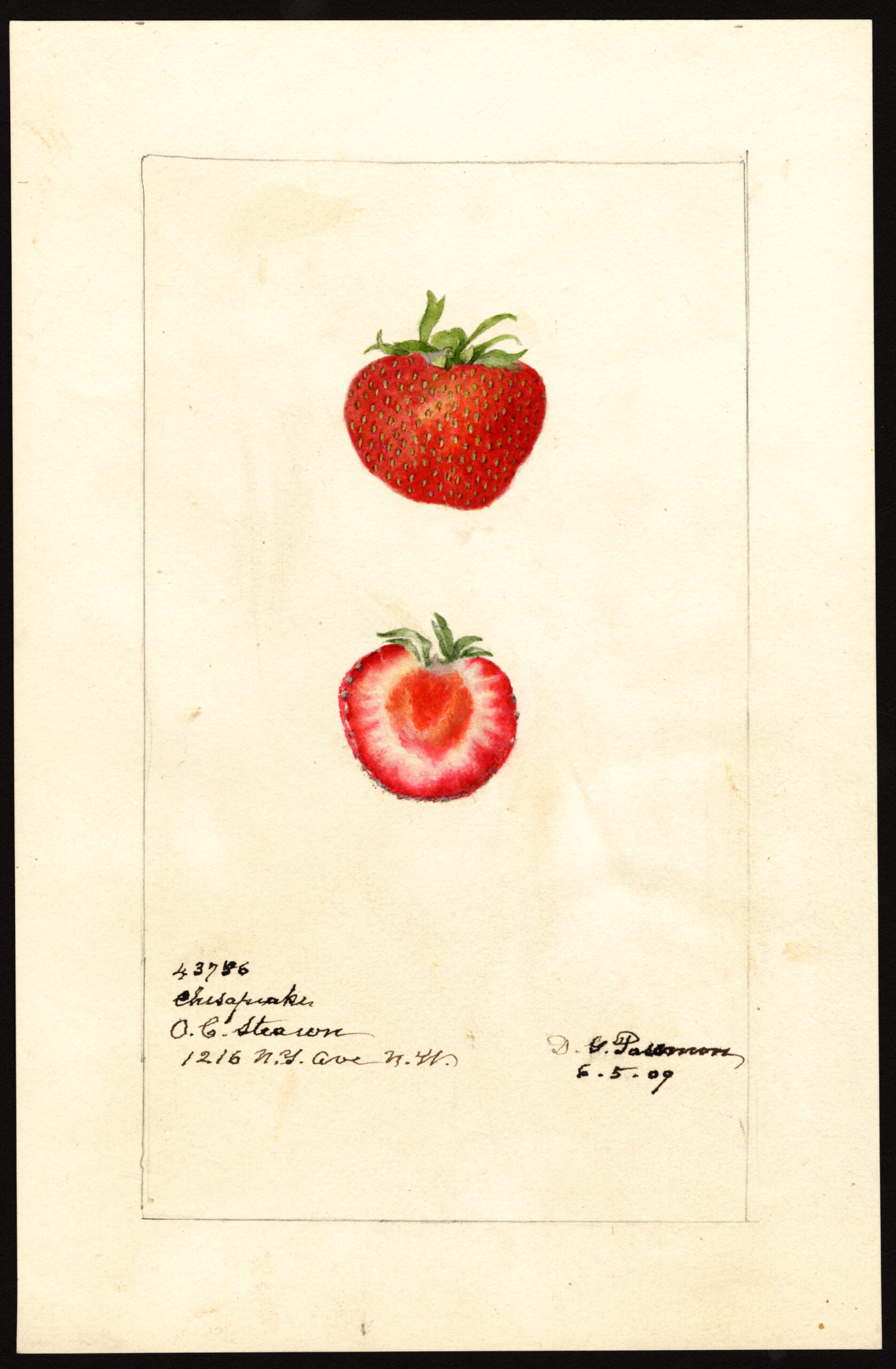

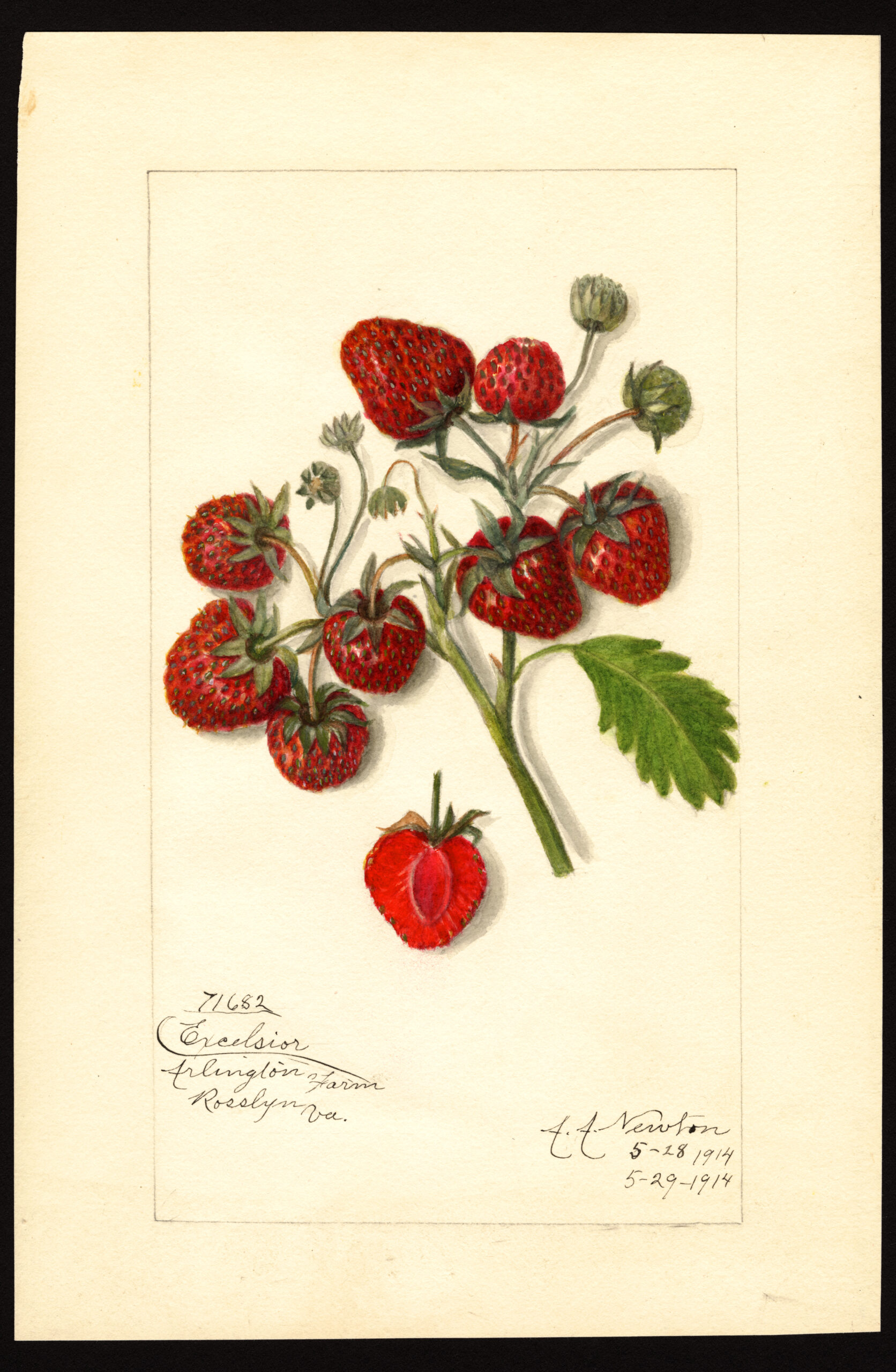

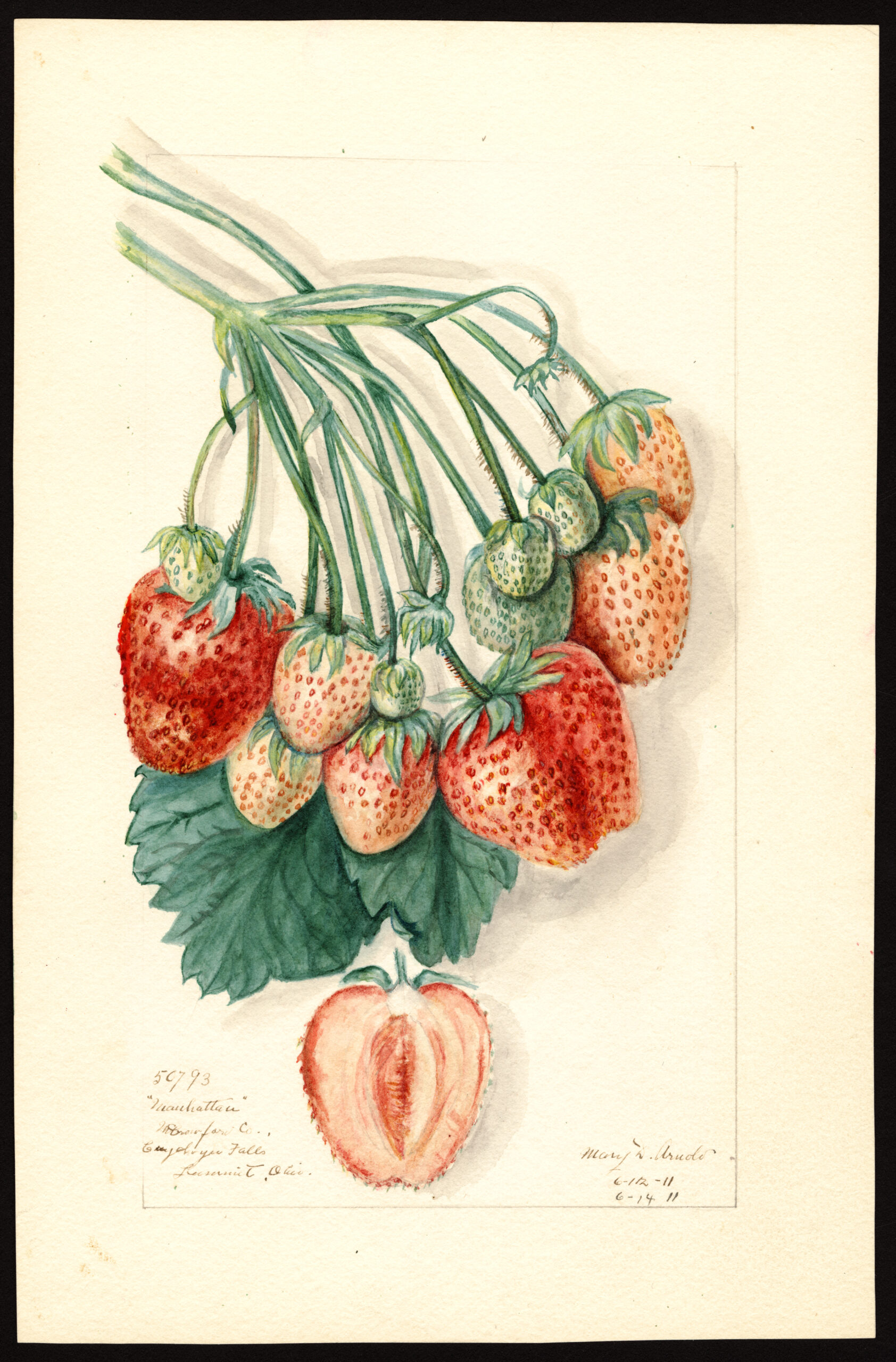

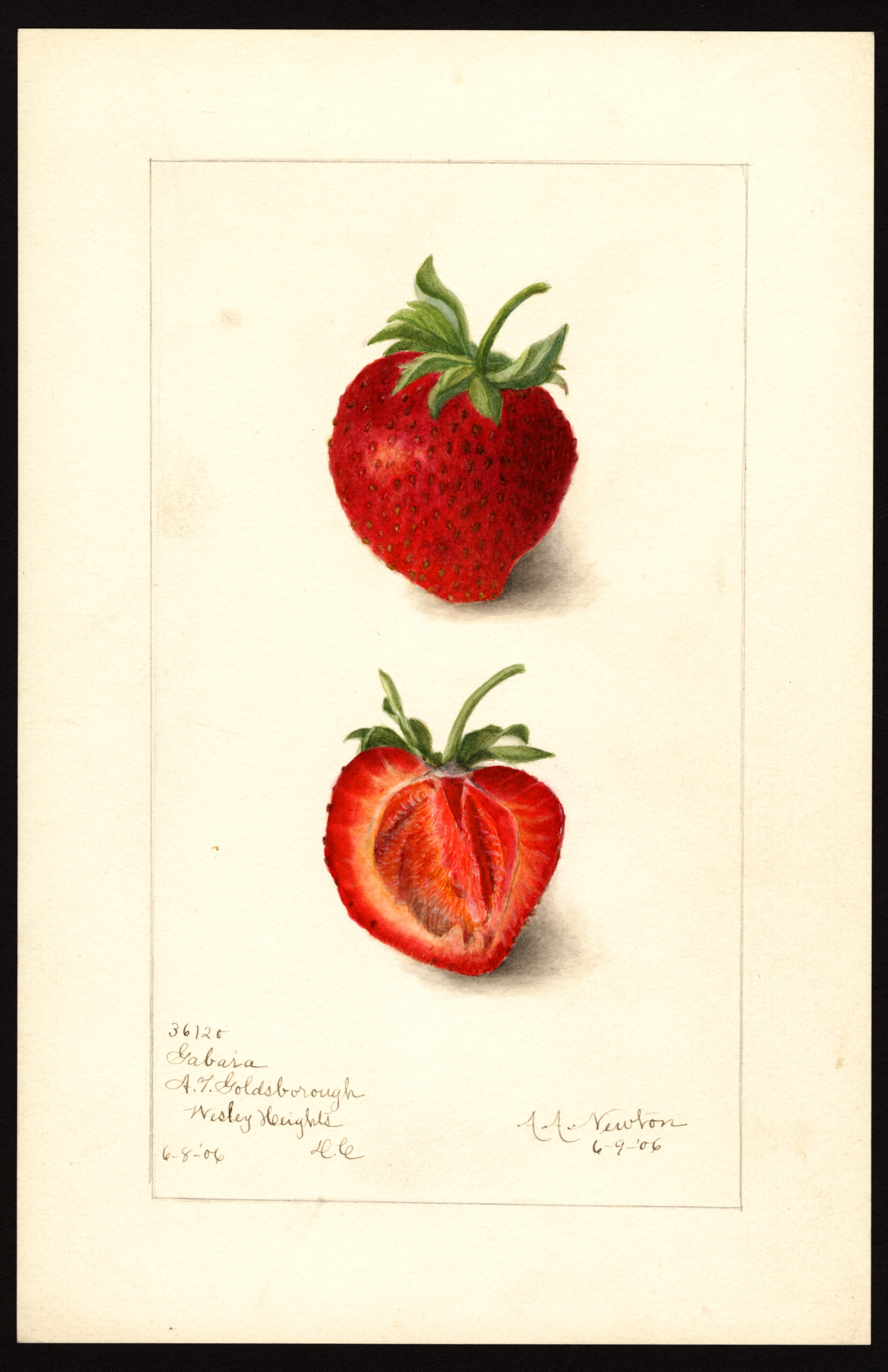

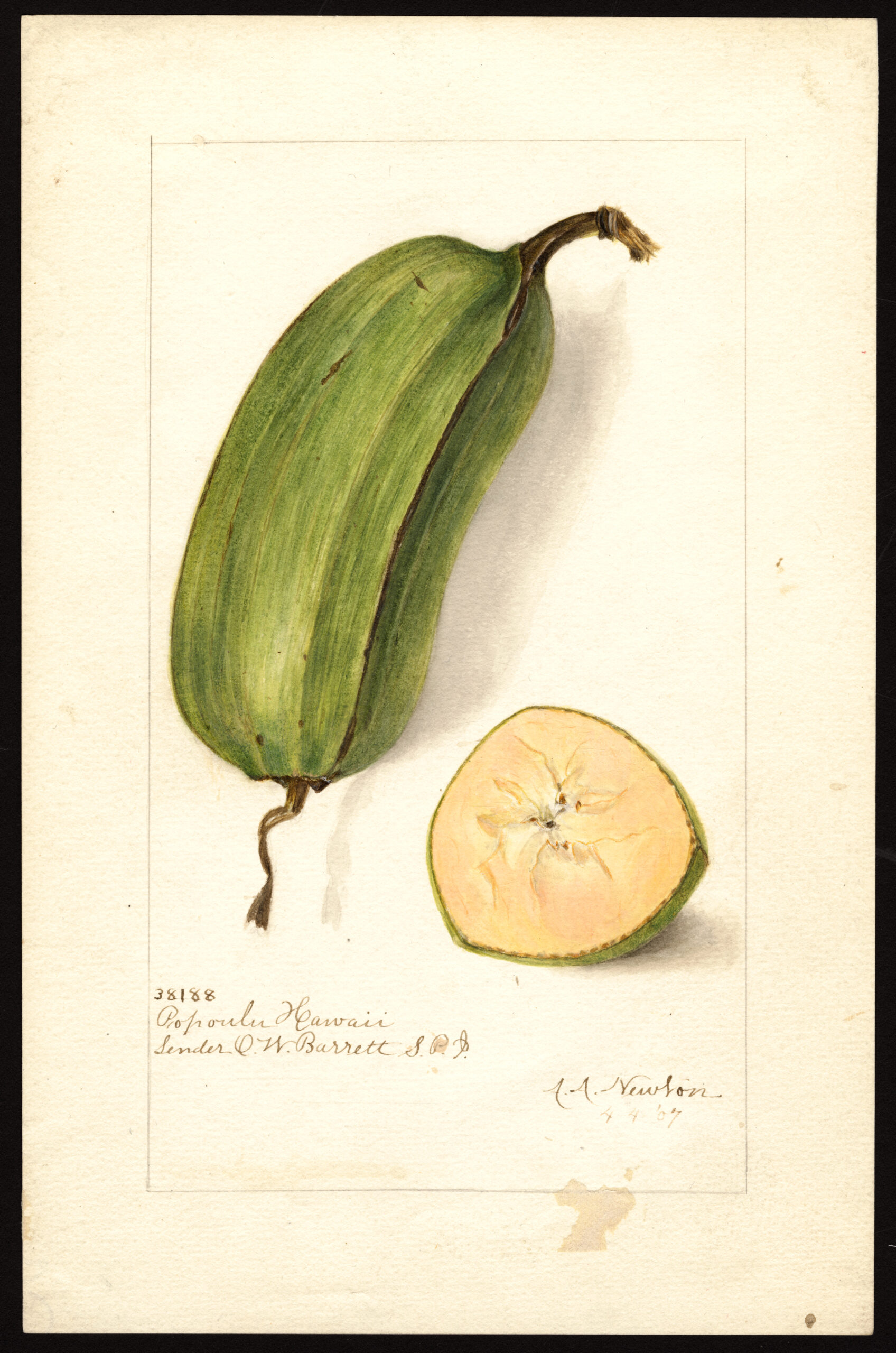

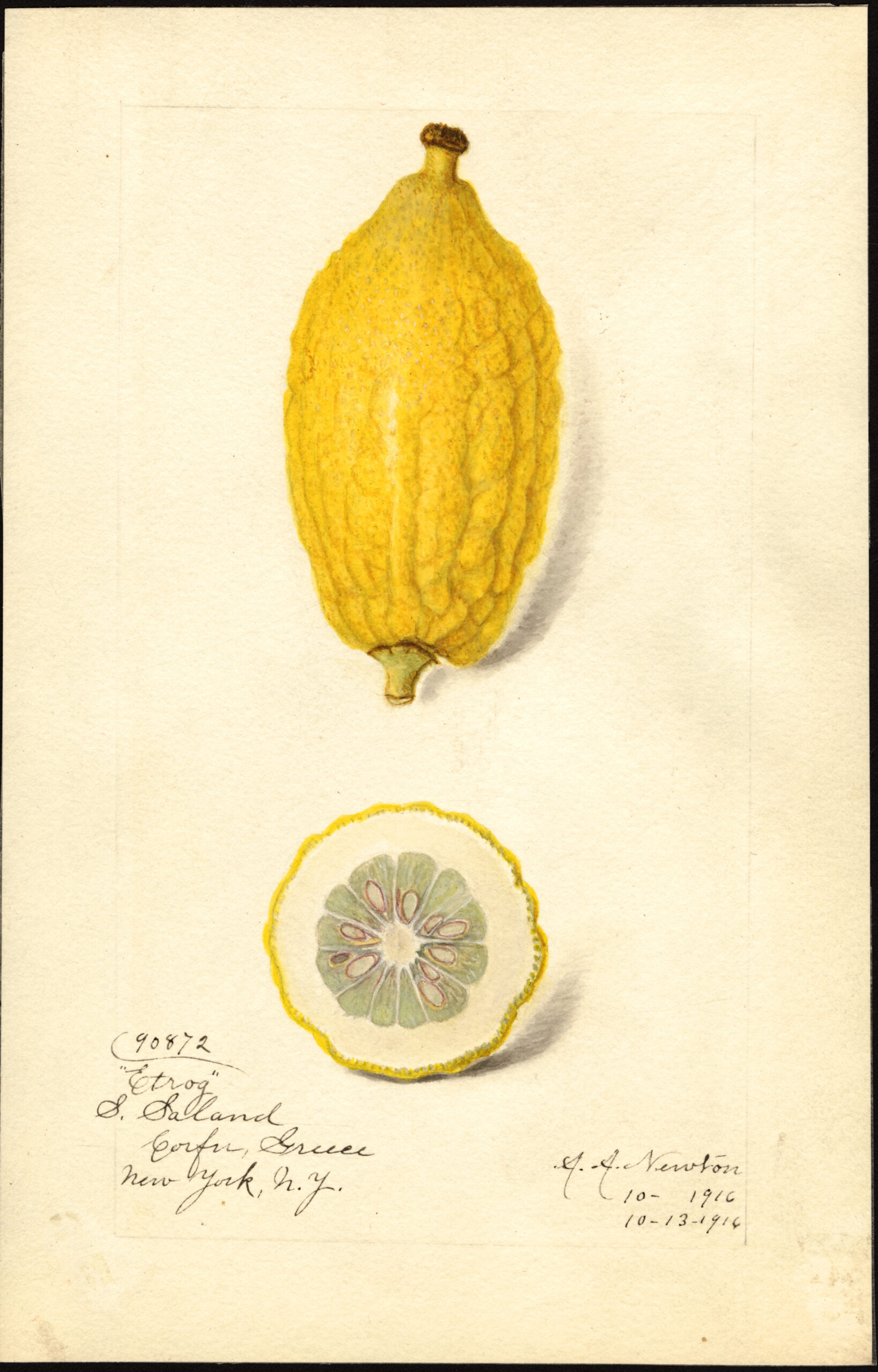

According to the Division of Pomology’s first chief, Henry E. Van Deman, the artists’ mandate was to capture “the natural size, shape, and color of both the exterior and interior of the fruit, with the leaves and twigs characteristic of each.”

If a specimen was going bad, the artist was under strict orders to represent the damage faithfully — no prettying things up.

As Alice Tangerini, staff illustrator and curator for botanical art in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History writes, “botanical illustrators and their works serve the scientist, depict(ing) what a botanist describes, acting as the proofreader for the scientific description:”

Digital photography, although increasingly used, cannot make judgements about the intricacies of portraying the plant parts a scientist may wish to emphasize and a camera cannot reconstruct a lifelike botanical specimen from dried, pressed material… the thought process mediating that decision of every aspect of the illustration lives in the head of the illustrator.

…the illustrator also has an eye for the aesthetics of botanical illustration, knowing that a drawing must capture the interest of the viewer to be a viable form of communication. Attention to accuracy is important, but excellence of style and technique used is also primary for an illustration to endure as a work of art and science.

Primary contributors Deborah Griscom Passmore, Mary Daisy Arnold, Amanda Almira Newton and their colleagues established norms for botanical illustration with their paintings for the USDA’s Pomological Watercolor Collection, simultaneously providing much-needed visual evidence for cultivators wishing to establish claims to their varietals.

(Fruit breeders’ rights were formally protected with the establishment of the Plant Patent Act of 1930, which decreed that anyone who “invented or discovered and asexually reproduced any distinct and new variety of plant” could receive a patent.)

The collection’s 7,497 watercolors of realistically-rendered fruits capture both the commonplace and the exotic in mouthwatering detail.

Both aesthetically and as a scientific database, the Pomological Watercolor Collection is the berries — specifically, Gandy, Chesapeake, Excelsior, Manhattan, and Gabara to namecheck but a few types of Fragaria, aka strawberries, preserved therein.

Other fruits remain lesser known on our shores. The USDA sponsored global expeditions specifically to gather specimens such as the ones below.

Queen Victoria reportedly offered knighthood to any traveler presenting her a mangosteen — still a rare treat in the west. They were banned in the U.S. until 2007 in the interest of protecting local agriculture from the threat of stowaway Asian fruit flies.

The thick, square-ended Popoulu banana would never be mistaken for a Chiquita from the outside. According to The World of Bananas in Hawai’i: Then and Now, its lineage dates back tens of thousands of years to the Vanuatu archipelago.

If you celebrate the harvest festival Sukkot, you likely encountered an etrog within the last month. The notoriously fiddly crop has been cultivated domestically since 1980, when a yeshiva student in Brooklyn, seeking to keep costs down and ensure that kosher protocols were maintained, convinced a third-generation California citrus grower by the name of Fitzgerald to give it a go.

Explore and download hi-res images from the Pomological Watercolor Collection here.

Related Content

A Collection of Vintage Fruit Crate Labels Offers a Voluptuous Vision of the Sunshine State

Via Aeon

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.