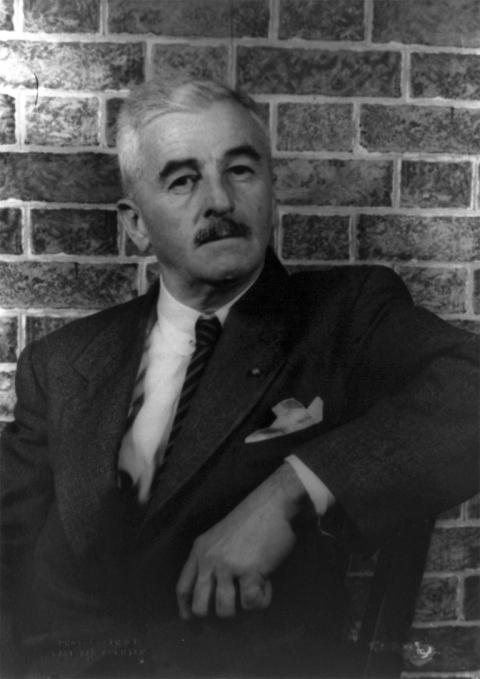

William Faulkner wrote his seventh novel As I Lay Dying in the last months of 1929, almost immediately after another stream-of-consciousness masterpiece, The Sound and the Fury. Like the Shakespearean title of that work, As I Lay Dying’s title, which comes from Homer’s Odyssey, indicates the literary ambitions of its author. Only thirty-two at the time of its writing, Faulkner composed the novel in eight weeks (six by his accounting) while working nights at the University of Mississippi’s power plant, deciding in advance that he would stake his entire reputation as a writer on the book: “Before I ever put pen to paper and set down the first words, I knew what the last word would be… Before I began I said, I am going to write a book by which, at a pinch, I can stand or fall if I never touch ink again.” His passionate conviction is evident in the original manuscript—the first and only draft—which reveals “an ease in creation unlike his other novels.”

Perhaps the most narratively straightforward of William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha novels—set in a fictional Mississippi region based on his own home county of Lafayette— As I Lay Dying tells the story of the Bundrens, a poor white family on a perilous journey to honor their matriarch Addie’s request for a burial in the town of Jefferson. Despite the seeming simplicity of its plot, the book’s style is incredibly complex, told from the perspective of fifteen different characters in rough-hewn country dialect and arresting lyrical fugues. It is the novel’s “coarse language and dialect,” that is “exactly Faulkner’s project,” writes Tin House editor Rob Spillman: “Faulkner, a Mississippi high school dropout, made it his mission to capture the emotional lives of the rural poor, unflinchingly writing about race, gender, sexuality, and power.” Through the power of his language and—in the words of Robert Penn Warren—the “range of effect, philosophical weight, originality of style, variety of characterization, humor, and tragic intensity,” the Southern novelist elevated his humble subjects to truly mythic status.

Thanks to HarperCollins, you can listen to Faulkner himself read from his masterpiece: .au file (4.4 Mb), .gsm file (0.9 Mb), .ra file (0.5 Mb). You’ll have to listen carefully to hear the author’s soft southern drawl, which gets lost at times in the poor quality recording. As you do, follow along with the text in Google Books. Faulkner reads from the twelfth chapter, told by Darl, Addie’s second oldest son, a sensitive, poetic thinker who narrates nineteen of the novel’s 59 chapters (and who James Franco plays in his film adaptation of the book). In this passage, Darl observes his mother’s death, and each family member’s immediate reaction, from sister Dewey Dell’s dramatic expressions of grief, to older brother Cash’s taciturn response and father Anse’s tragic-comic insensitivity: “God’s will be done…. Now I can get them teeth.”

To hear much more of Faulkner’s voice, visit Faulkner at Virginia: An Audio Archive, which catalogs and stores digital audio of the author’s lectures, readings, and question and answer sessions during his tenure as writer in residence at the University of Virginia in 1957–58. In one particular session with a group of engineering school students, Faulkner gives us a clue for how we might approach his work, which can seem so strange to those unfamiliar with the history, customs, and speech patterns of the American Deep South. Each of us, he says, “reads into the—the books, things the writer didn’t put in there, in the terms that—that his and the writer’s experience could not possibly be identical. That there are things the writer might think is in that book, which the reader doesn’t find for the same reason that—that no two experiences can be identical, but everyone reads according to—to his own—own lights, his own experience, his own observation, imagination, and experience.” For all of their provincial peculiarities, the Bundren’s epic struggle with the grief and pain of loss has universal reach and resonance.

Related Content:

William Faulkner Names His Best Novel, And the First Faulkner Novel You Should Read

William Faulkner Reads His Nobel Prize Speech

Seven Tips From William Faulkner on How to Write Fiction

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness