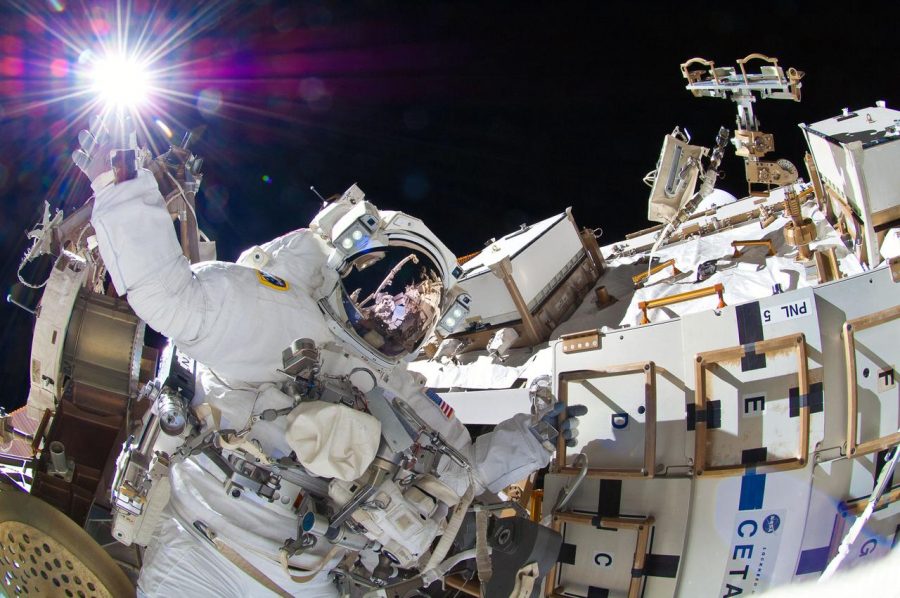

Last summer, astronomer Michael Summer wrote that, despite a relatively low profile, NASA and its international partners have been “living Carl Sagan’s dream for space exploration.” Summers’ catalogue of discoveries and groundbreaking experiments—such as Scott Kelly’s yearlong stay aboard the International Space Station—speaks for itself. But for those focused on more earthbound concerns, or those less emotionally moved by science, it may take a certain eloquence to communicate the value of space in words. “Perhaps,” writes Summers, “we should have had a poet as a member of every space mission to better capture the intense thrill of discovery.”

Sagan was the closest we’ve come. Though he never went into space himself, he worked closely on NASA missions since the 1950s and communicated better than anyone, in deeply poetic terms, the beauty and wonder of the cosmos. Likely you’re familiar with his “pale blue dot” soliloquy, but consider this quote from his 1968 lectures, Planetary Exploration:

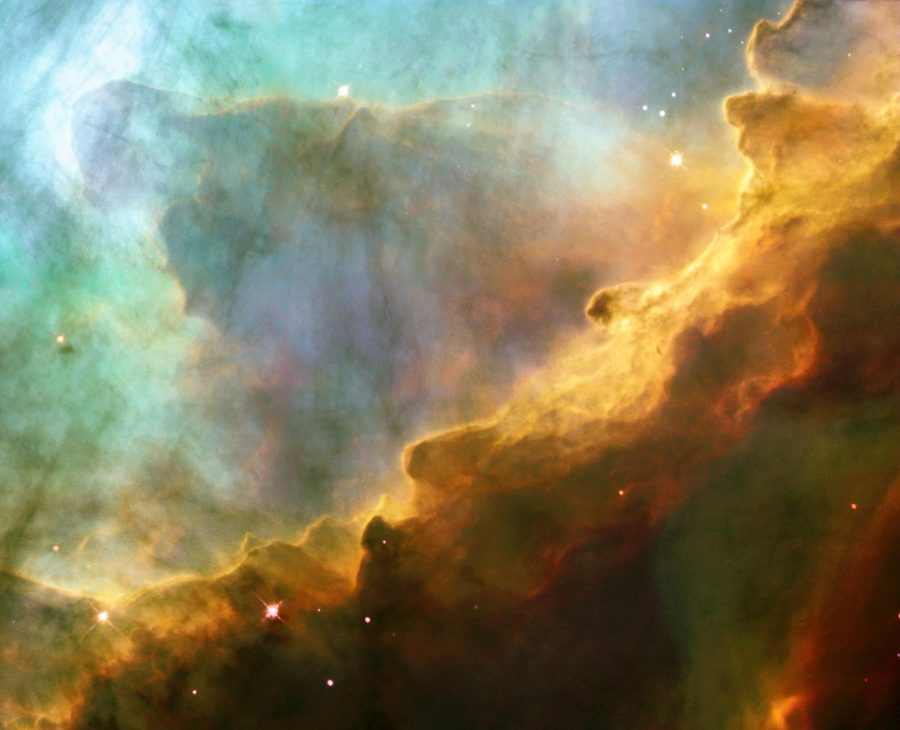

There is a place with four suns in the sky — red, white, blue, and yellow; two of them are so close together that they touch, and star-stuff flows between them. I know of a world with a million moons. I know of a sun the size of the Earth — and made of diamond. There are atomic nuclei a few miles across which rotate thirty times a second. There are tiny grains between the stars, with the size and atomic composition of bacteria. There are stars leaving the Milky Way, and immense gas clouds falling into it. There are turbulent plasmas writhing with X- and gamma-rays and mighty stellar explosions. There are, perhaps, places which are outside our universe. The universe is vast and awesome, and for the first time we are becoming a part of it.

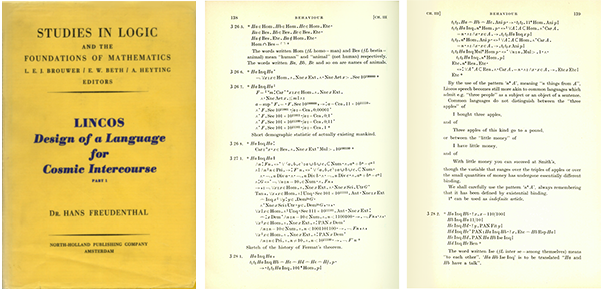

Sagan’s lyrical prose alone captured the imagination of millions. But what has most often made us to fall in love with, and fund, the space program, is photography. No mission has ever had a resident poet, but every one, manned and unmanned, has had multiple high-tech photographers.

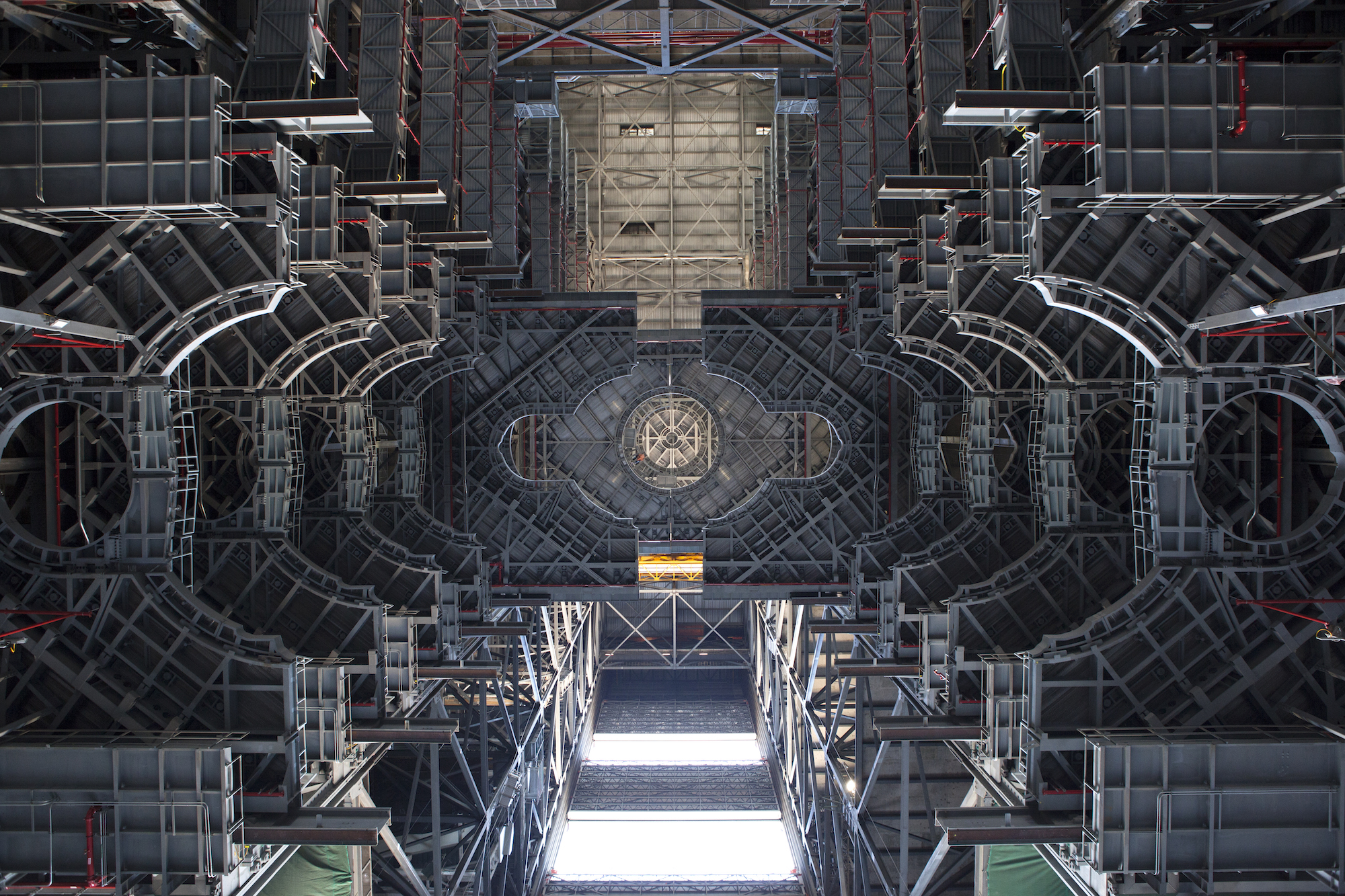

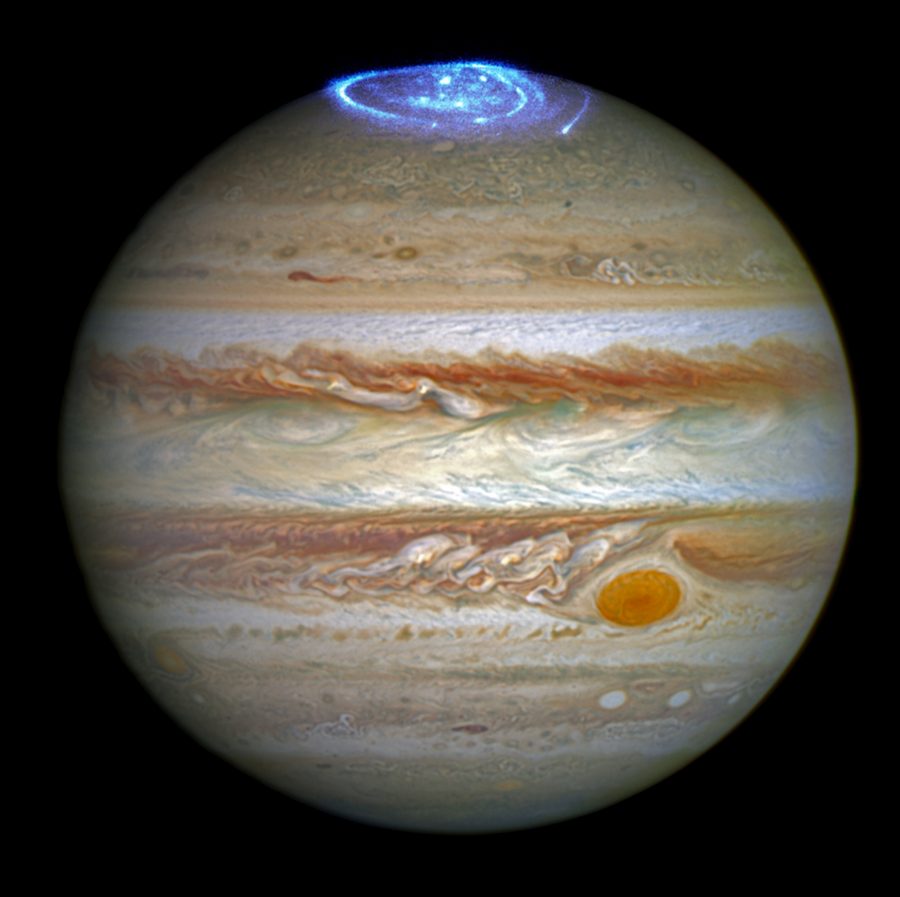

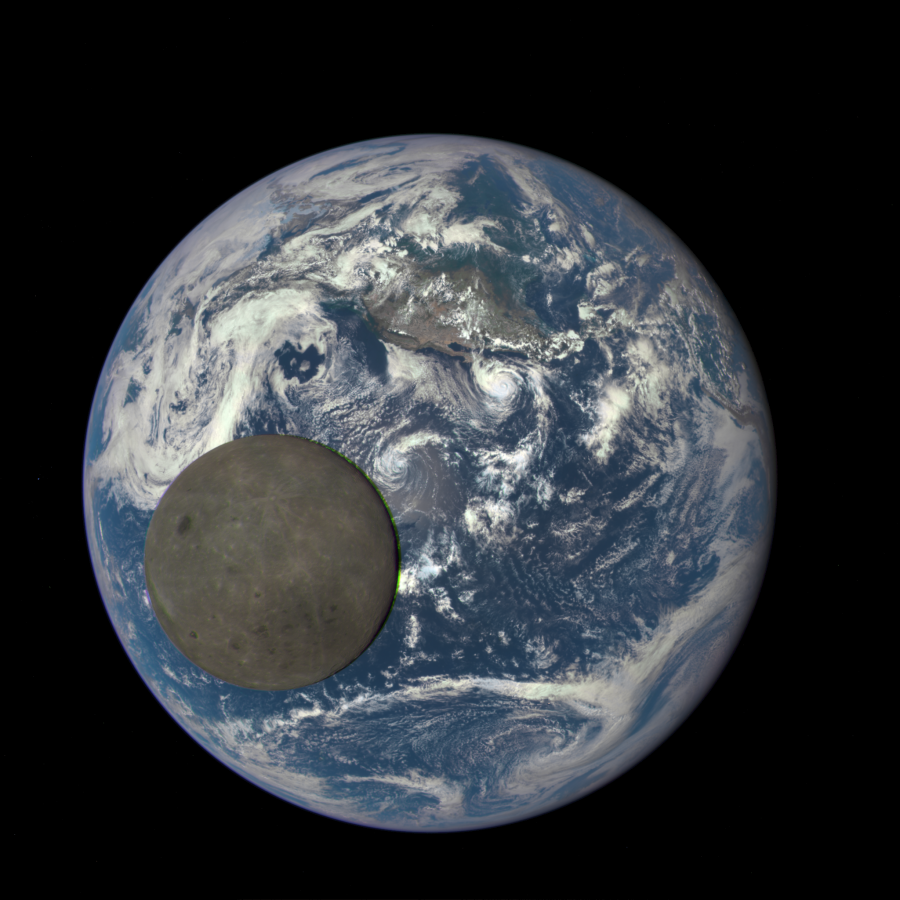

NASA has long had “a trove of images, audio, and video the general public wanted to see,” writes Eric Berger at Ars Technica. “After all, this was the agency that had sent people to the Moon, taken photos of every planet in the Solar System, and launched the Hubble Space Telescope.”

Until the advent of the Internet, only a few select, and unforgettable, images made their way to the public. Since the 1990s, the agency has published hundreds of photos and videos online, but these efforts have been fragmentary and not particularly user-friendly. That changed this month with the release of a huge photo archive—140,000 pictures, videos, and audio files, to be exact—that aggregates materials from the agency’s centers all across the country and the world, and makes them searchable. The visual poetry on display is staggering, as is the amount of technical information for the more technically inclined.

Since Summers lauded NASA’s accomplishments, the fraught politics of science funding have become deeply concerning for scientists and the public, provoking what will likely be a well-attended march for science tomorrow. Where does NASA stand in all of this? You may be surprised to learn that the president has signed a bill authorizing considerable funding for the agency. You may be unsurprised to learn how that funding is to be allocated. Earth science and education are out. A mission to Mars is in.

As I perused the stunning NASA photo archive, picking my jaw up from the floor several times, I found in some cases that my view began to shift, especially while looking at photos from the Mars rover missions, and reading the captions, which casually refer to every rocky outcropping, mountain, crater, and valley by name as though they were tourist destinations on a map of New Mexico. In addition to Sagan’s Cosmos, I also began to think of the colonization epics of Ray Bradbury and Kim Stanley Robinson—the corporate greed, the apocalyptic wars, the history repeating itself on another planet….

It’s easy to blame the current anti-science lobby for shifting the focus to planets other than our own. There is no justification for the mutually assured destruction of climate science denialism or nuclear escalation. But in addition to mapping and naming galaxies, black holes, and nebulae, we’ve seen an intense focus on the Red Planet for many years. It seems inevitable, as it did to the most far-sighted of science fiction writers, that we would make our way there one way or another.

We would do well to recover the sense of awe and wonder outer space used to inspire in us—sublime feelings that can motivate us not only to explore the seemingly limitless resources of space but to conserve and preserve our own on Earth. Hopefully you can find your own slice of the sublime in this massive photo archive.

Related Content:

How the Iconic 1968 “Earthrise” Photo Was Made: An Engrossing Visualization by NASA

NASA Releases 3 Million Thermal Images of Our Planet Earth

NASA Its Software Online & Makes It Free to Download

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness