The first photo of the moon was taken in 1850 by Louis Daguerre, from whom the daguerrotype gets its name. We have no idea what that first image looked like as it was lost in a studio fire. But the need to catalog the heavens with modern tools had started, and was both fascinating as it was lacking. Into this evolution of science and art stepped Étienne Léopold Trouvelot, the French immigrant, living in the States, an amateur scientist and an illustrator. He would dismiss photography of the heavens as “so blurred and indistinct that no details of any great value can be secured.” And by illustrating instead by he saw through telescopes, he secured a place in art *and* science history.

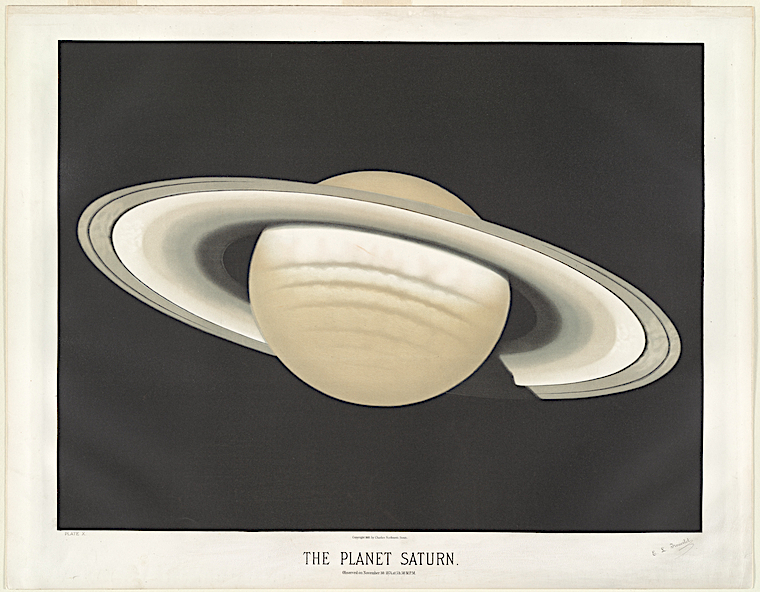

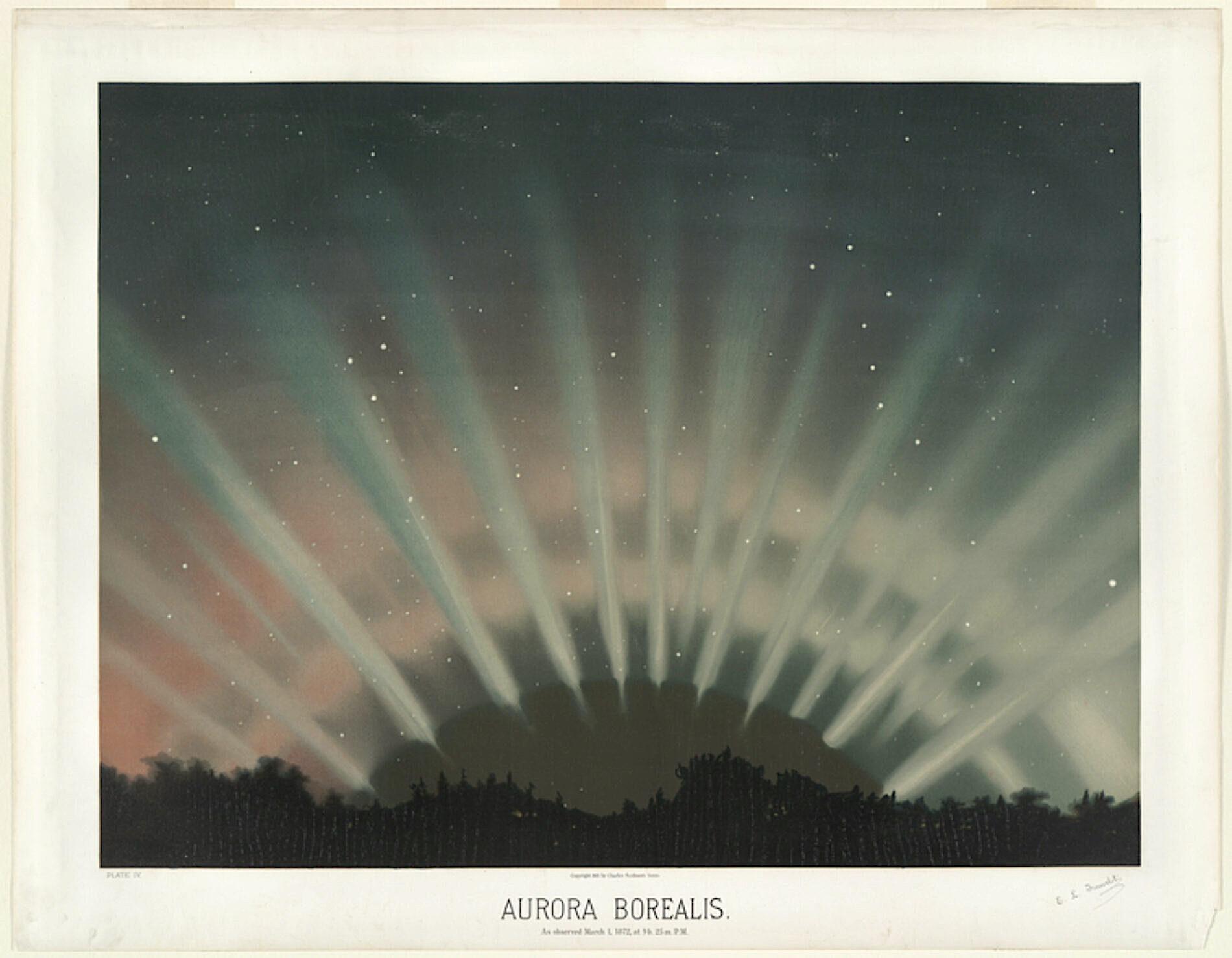

Trouvelot might have thought his scientific papers would be his legacy. He wrote fifty in his lifetime. Instead it is his roughly 7,000 illustrations of planets, comets, and other phenomena that still please us to this day. The New York Public Library has put 15 of his best up on their site, and over at this page, you can compare what Trouvelot saw—-the great astronomer Emma Converse called Trouvelot the “prince of observers”—-to photos from NASA’s archive.

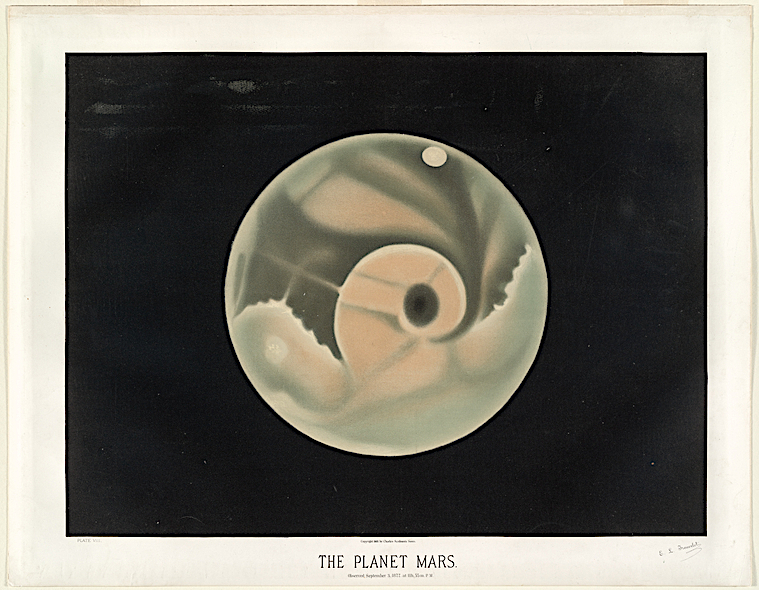

Even if his Mars is a bit fanciful, looking translucent like a fish egg, his understanding of the planet echoes in the following century of sci-fi paranoia. Something strange must be there, he suggests.

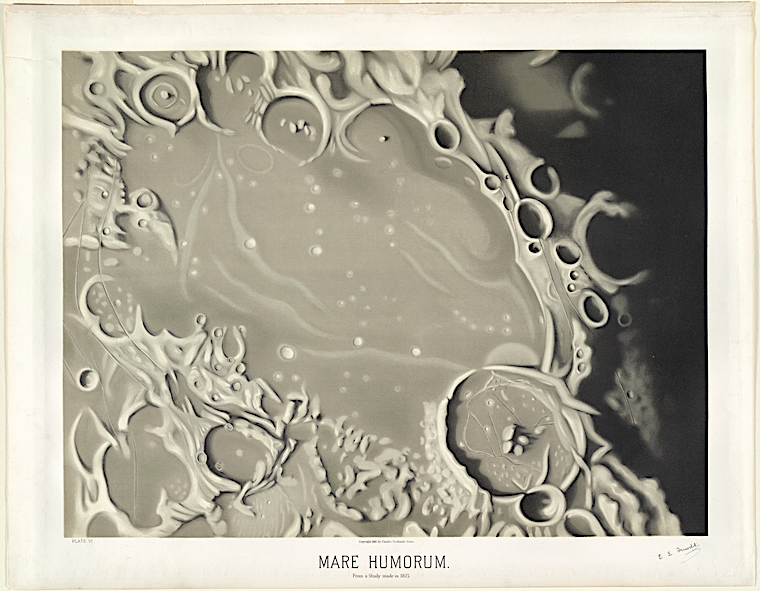

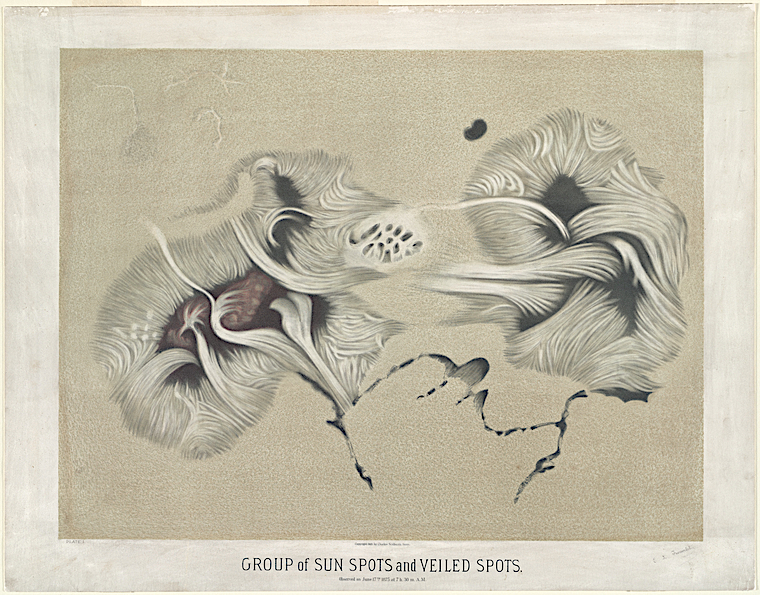

Harvard hired him to sketch at their college’s observatory, and he used pastels to bring the planets to life. Engraving or ink would not have worked as well as these soft shapes and determined lines. His rendering of the moon surface is accurate but also fanciful, like whipped cream. And his sun spots might not be accurate, but they replicated the god-like forces at work on its tumultuous surface. His Saturn is the most realistic of them all. Even the NASA image doesn’t look too different to Trouvelot’s art.

These images also help rehabilitate Trouvelot’s other legacy—-the dreaded Gypsy Moth. Before his stint as amateur scientist, he was also an amateur entomologist, and while researching silkworms and silk production, accidentally let European gypsy moths into North America, where they wreaked havoc on the forests of North America. Saturn’s rings may look the same back then as they do now, but so does the damage of the gypsy moth, which according to Wikipedia is up to $868 million in damages per year.

Related Content:

A 9th Century Manuscript Teaches Astronomy by Making Sublime Pictures Out of Words

Jocelyn Bell Burnell Changed Astronomy Forever; Her Ph.D. Advisor Won the Nobel Prize for It

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.