The close associations between Surrealism and Freudian psychoanalysis were liberally encouraged by the most famous proponent of the movement, Salvador Dalí, who considered himself a devoted follower of Freud. We don’t have to wonder what the founder of psychoanalysis would have thought of his self-appointed protégé.

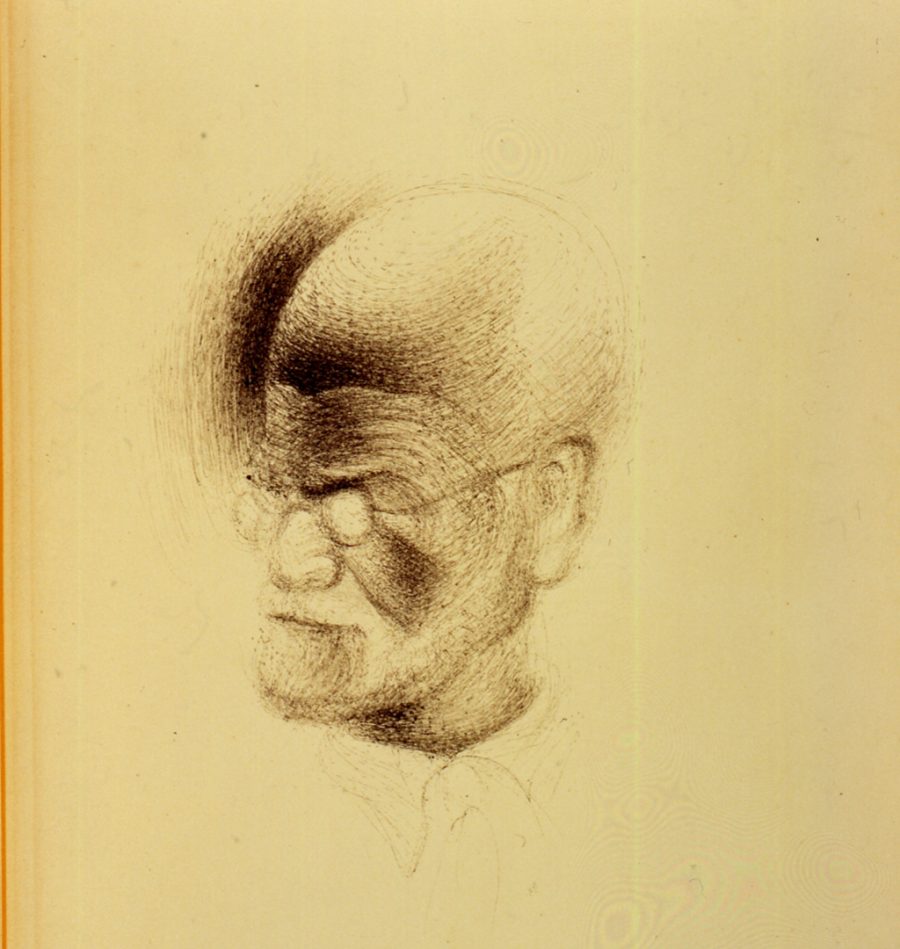

We have them recording, in their own words, their impressions of their one and only meeting—which took place in July of 1938, at Freud’s home in London. Freud was 81, Dali 34. We also have sketches Dali made of Freud while the two sat together. Their memories of events, shall we say, differ considerably, or at least they seemed totally bewildered by each other. (Freud pronounced Dali a “fanatic.”)

In any case, There’s absolutely no way the encounter could have lived up to Dali’s expectations, as the Freud Museum London notes:

[Dalí] had already travelled to Vienna several times but failed to make an introduction. Instead, he wrote in his autobiography, he spent his time having “long and exhaustive imaginary conversations” with his hero, at one point fantasizing that he “came home with me and stayed all night clinging to the curtains of my room in the Hotel Sacher.”

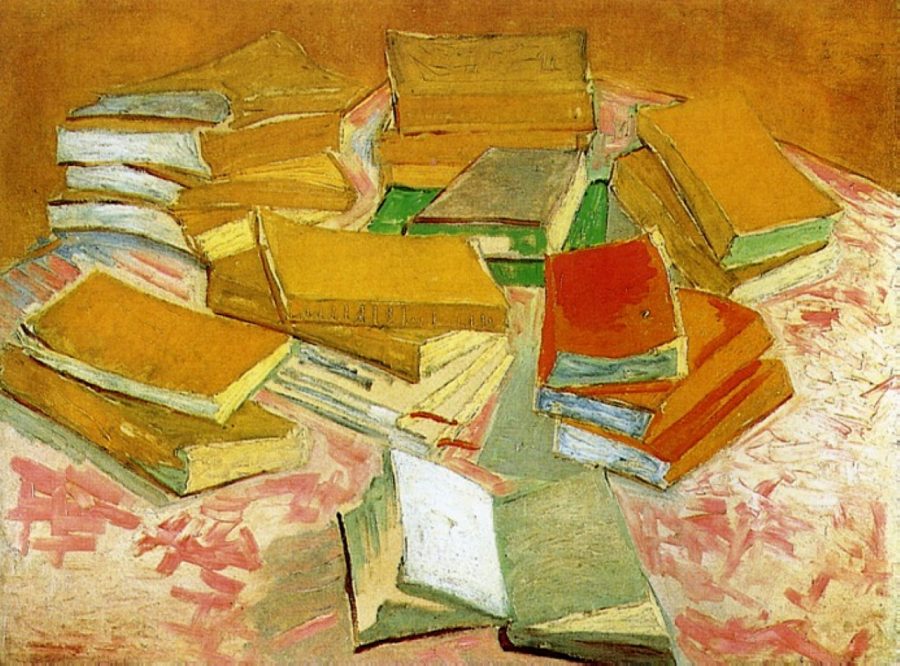

Freud was certainly not going to indulge Dalí’s peculiar fantasies, but what the artist really wanted was validation of his work—and maybe his very being. “Dali had spent his teens and early twenties reading Freud’s works on the unconscious,” writes Paul Gallagher at Dangerous Minds, “on sexuality and The Interpretation of Dreams.” He was obsessed. Finally meeting Freud in ’38, he must have felt “like a believer might feel when coming face-to-face with God.”

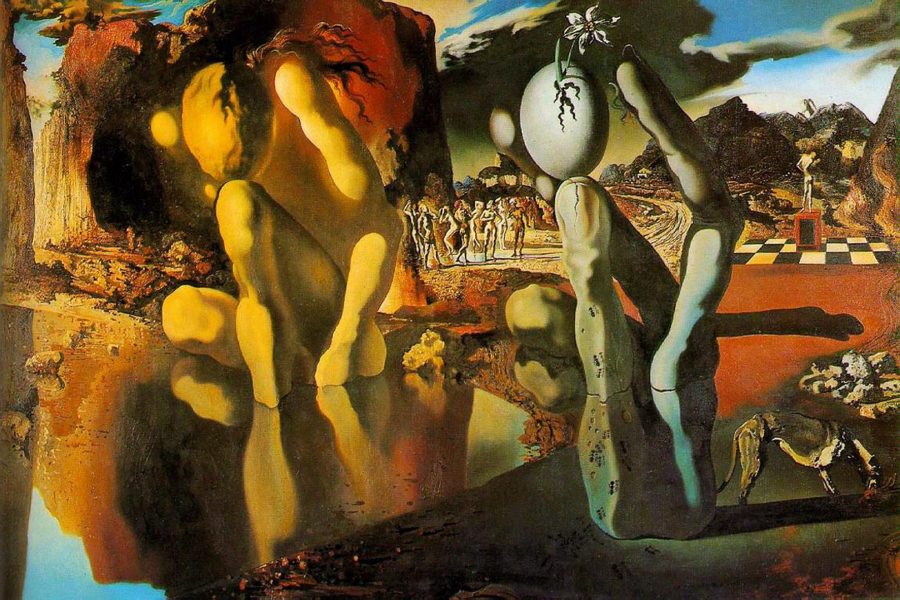

He brought with him his latest painting The Metamorphosis of Narcissus, and an article he had published on paranoia. This, especially, Dali hoped would gain the respect of the elderly Freud.

Trying to interest him, I explained that it was not a surrealist diversion, but was really an ambitiously scientific article, and I repeated the title, pointing to it at the same time with my finger. Before his imperturbable indifference, my voice became involuntarily sharper and more insistent.

On being shown the painting, Freud supposedly said, “in classic paintings I look for the unconscious, but in your paintings I look for the conscious.” The comment stung, though Dali wasn’t entirely sure what it meant. But he took it as further evidence that the meeting was a bust. Sketching Freud in the drawing below, he wrote, “Freud’s cranium is a snail! His brain is in the form of a spiral—to be extracted with a needle!”

One might see why Freud was suspicious of Surrealists, “who have apparently chosen me as their patron saint,” he wrote to Stefan Zweig, the mutual friend who introduced him to Dali. In 1921, poet and Surrealist manifesto writer André Breton “had shown up uninvited on [Freud’s] doorstep.” Unhappy with his reception, Breton published a “bitter attack,” calling Freud an “old man without elegance” and later accused Freud of plagiarizing him.

Despite the memory of this nastiness, and Freud’s general distaste for modern art, he couldn’t help but be impressed with Dali. “Until then,” he wrote to Zweig, “I was inclined to look upon the surrealists… as absolute (let us say 95 percent, like alcohol), cranks. That young Spaniard, however, with his candid and fanatical eyes, and his undeniable technical mastery, has made me reconsider my opinion.”

Related Content:

The Famous Break Up of Sigmund Freud & Carl Jung Explained in a New Animated Video

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness