Since the first stirrings of the internet, artists and curators have puzzled over what the fluidity of online space would do to the experience of viewing works of art. At a conference on the subject in 2001, Susan Hazan of the Israel Museum wondered whether there is “space for enchantment in a technological world?” She referred to Walter Benjamin’s ruminations on the “potentially liberating phenomenon” of technologically reproduced art, yet also noted that “what was forfeited in this process were the ‘aura’ and the authority of the object containing within it the values of cultural heritage and tradition.” Evaluating a number of online galleries of the time, Hazan found that “the speed with which we are able to access remote museums and pull them up side by side on the screen is alarmingly immediate.” Perhaps the “accelerated mobility” of the internet, she worried, “causes objects to become disposable and to decline in significance.”

Fifteen years after her essay, the number of museums that have made their collections available online whole, or in part, has grown exponentially and shows no signs of slowing. We may not need to fear losing museums and libraries—important spaces that Michel Foucault called “heterotopias,” where linear, mundane time is interrupted. These spaces will likely always exist.

Yet increasingly we need never visit them in person to view most of their contents. Students and academics can conduct nearly all of their research through the internet, never having to travel to the Bodleian, the Beinecke, or the British Library. And lovers of art must no longer shell out for plane tickets and hotels to see the precious contents of the Getty, the Guggenheim, or the Rijksmuseum. And who would dare do that during our current pandemic?

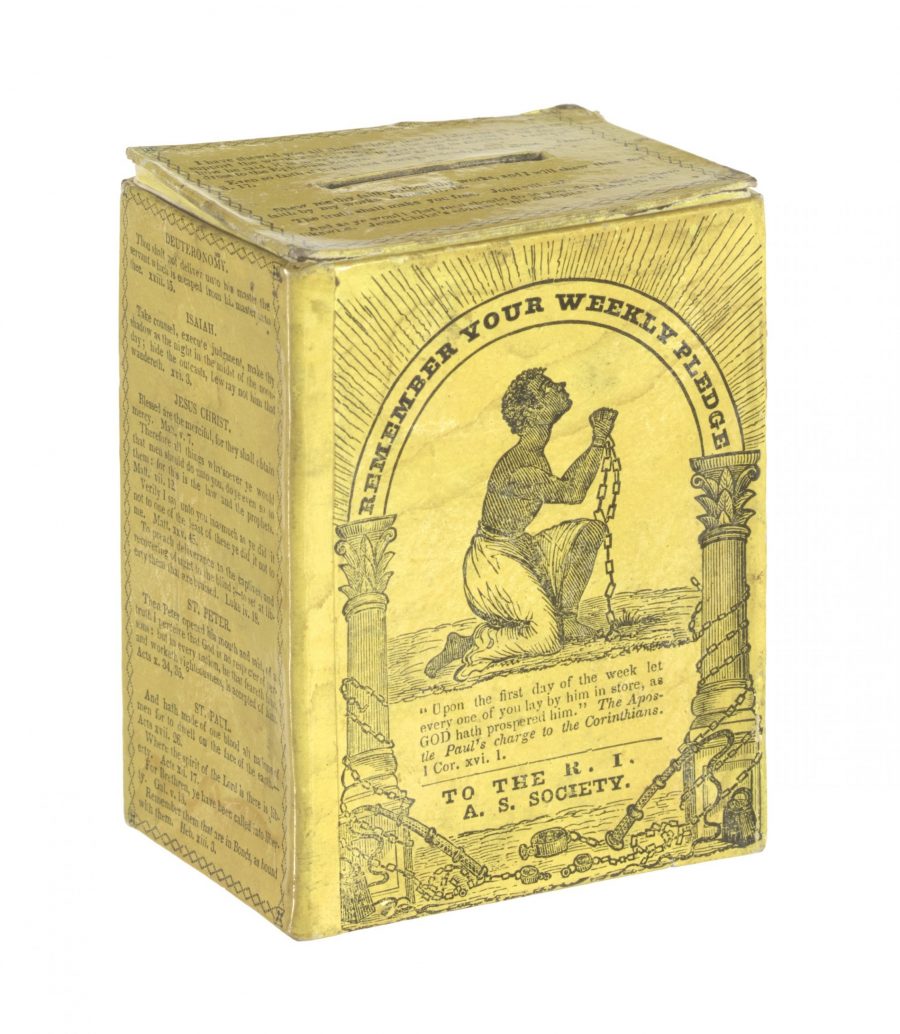

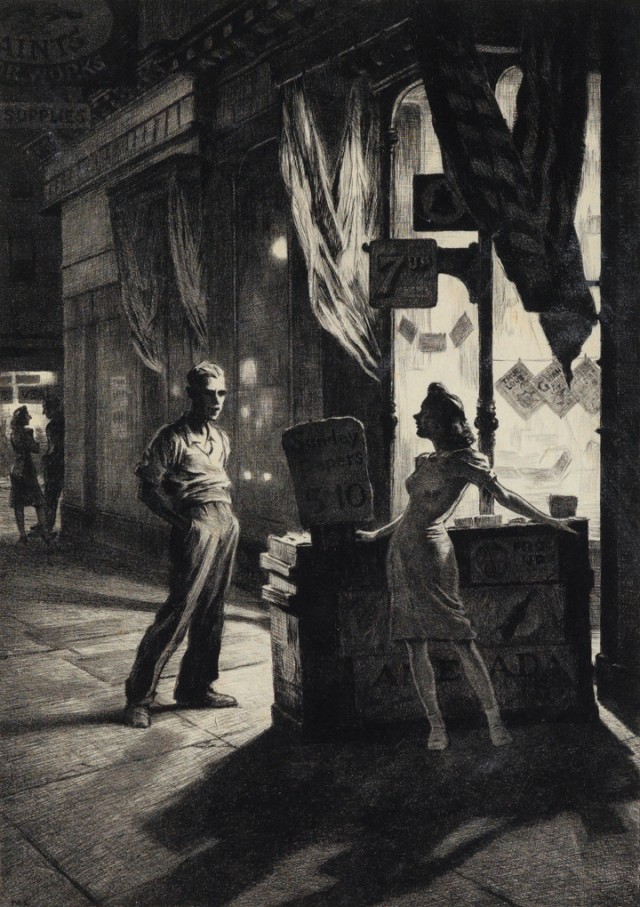

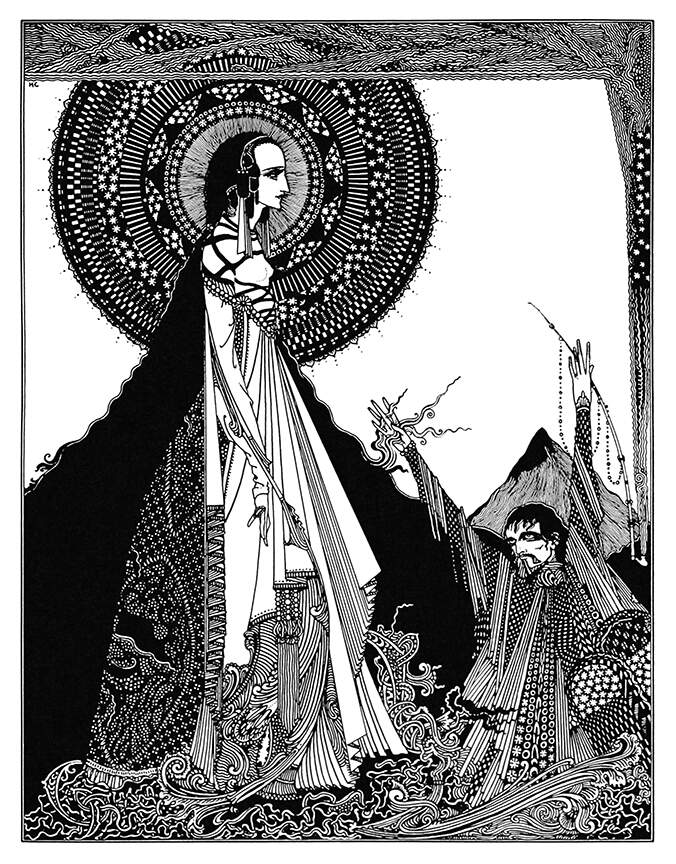

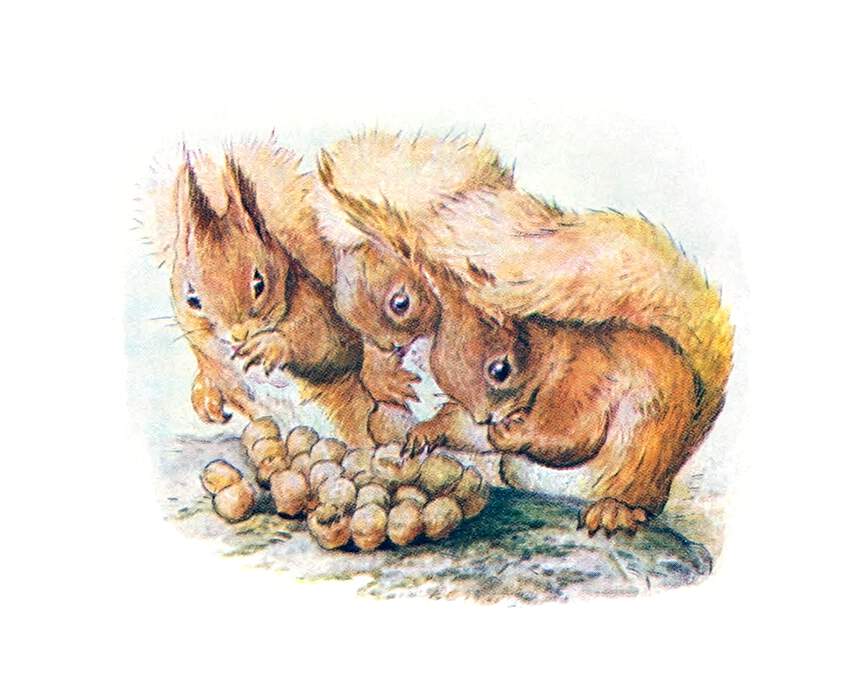

For all that may be lost, online galleries have long been “making works of art widely available, introducing new forms of perception in film and photography and allowing art to move from private to public, from the elite to the masses.”

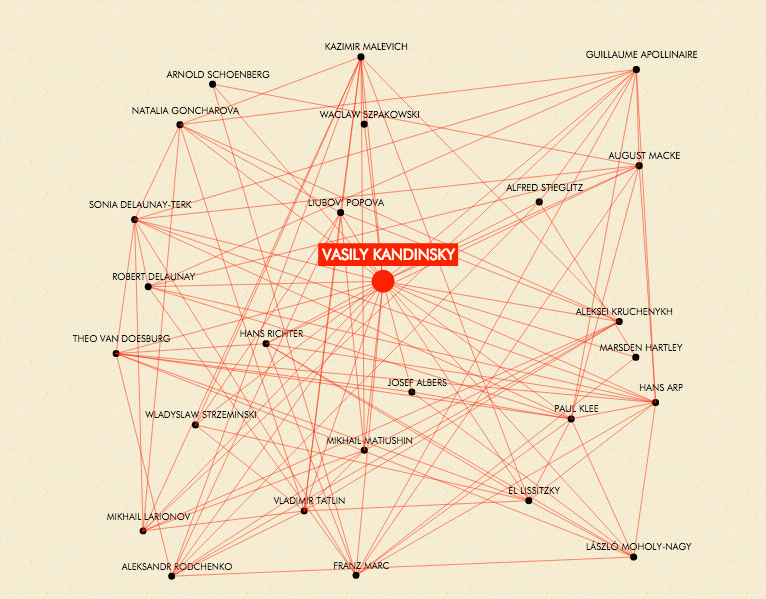

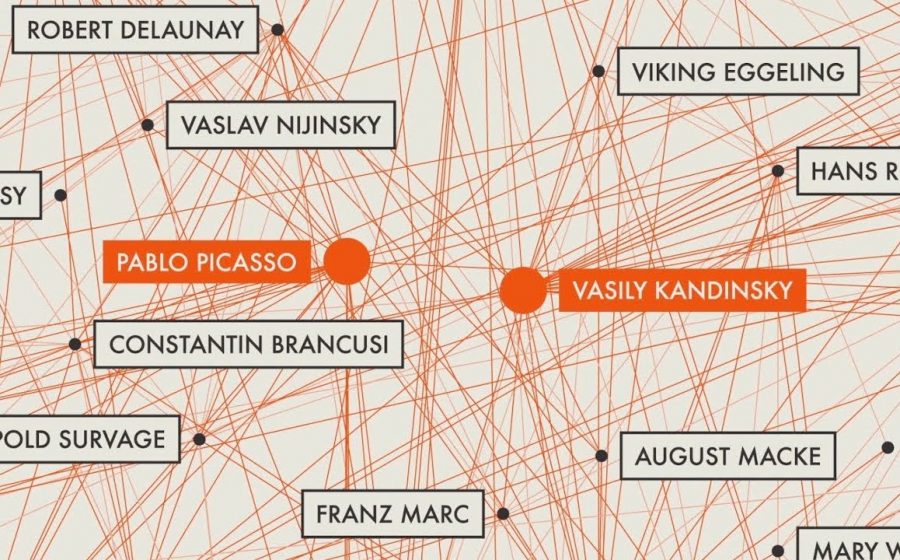

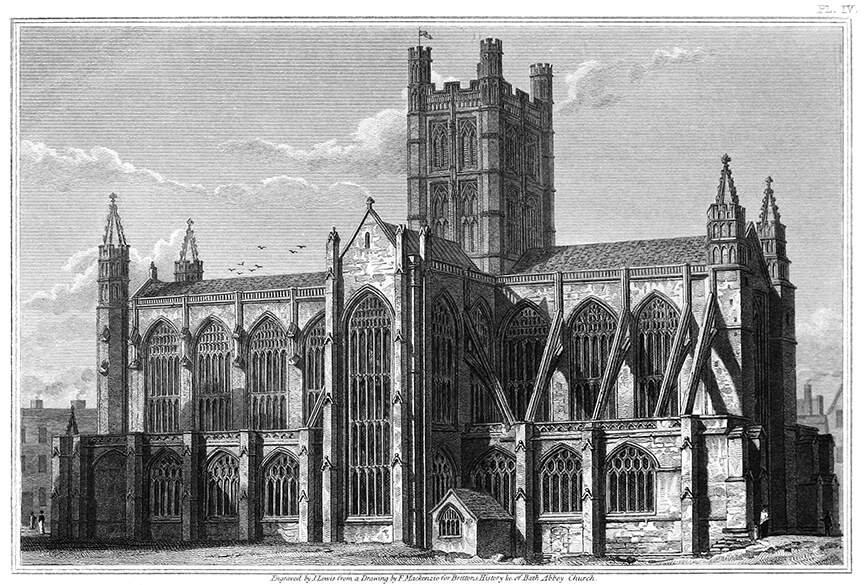

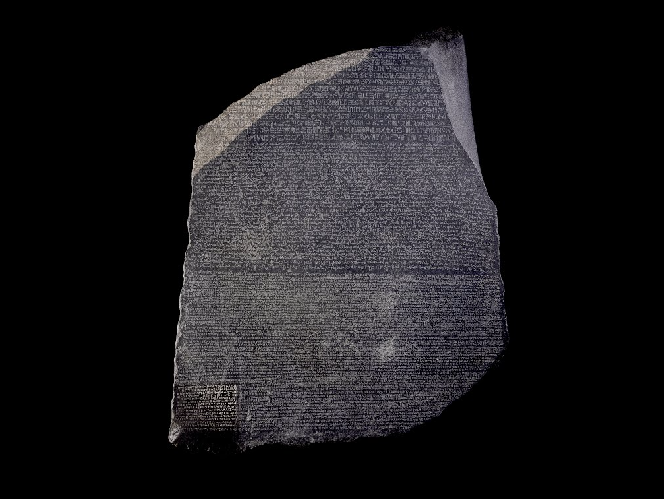

Even more so than when Hazan wrote those words, the online world offers possibilities for “the emergence of new cultural phenomena, the virtual aura.” Over the years we have featured dozens of databases, archives, and online galleries through which you might virtually experience art the world over, an experience once solely reserved for only the very wealthy. And as artists and curators adapt to a digital environment, they find new ways to make virtual galleries enchanting. The vast collections in the virtual galleries listed below await your visit, with 2,000,000+ paintings, sculptures, photographs, books, and more. See the Rosetta Stone at the British Museum (top), courtesy of the Google Cultural Institute. See Van Gogh’s many self-portraits and vivid, swirling landscapes at The Van Gogh Museum. Visit the Asian art collection at the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler Galleries. Or see Vassily Kandinsky’s dazzling abstract compositions at the Guggenheim.

And below the list of galleries, find links to online collections of several hundred art books to read online or download. Continue to watch this space: We’ll add to both of these lists as more and more collections come online.

Art Images from Museums & Libraries

- Art Institute of Chicago (44,000 images)

- Google Art Project (250,000)

- Harvard Bauhaus Collection (30,000)

- L.A. County Museum (20,000)

- New York Public Library-Historic Maps (20,000)

- Norway National Museum (30,000)

- Paris Art Museums (300,000)

- SFMoMA Rauschenberg Collection

- Stanford University’s Cantor Art Center (45,000)

- Stanford University’s French Revolution Collection (14,000)

- Taipei’s National Palace Museum (70,000)

- The British Library (100,000)

- The British Museum (4,200)

- The Cleveland Museum of Art (30,000)

- The Isamu Noguchi Museum (60,000)

- The Getty (100,000)

- The Guggenheim (1,600)

- The Met (400,000)

- The Morgan Library & Museum’s Online Collection (10,000)

- The Morgan Library Rembrandt Sketches (300)

- The Museum of Modern Art/MoMA (65,000)

- The Museum of New Zealand (30,000)

- The National Gallery (35,000)

- The New York Public Library: Photos, Maps, Letters (180,000)

- The Rijksmuseum (210,00)

- The Smithsonian (40,000)

- The Tate (70,000)

- The Whitney (21,000)

- The Van Gogh Museum (3500)

- Yale Center for British Art

- Yale’s Great Depression Photo Collection (170,000)

- Vermeer (36)

Art Books

- The Getty (250 books)

- The Guggenheim (98)

- The Met (448)

- Getty Research Portal (100,000)

Note: This post originally appeared on our site in May 2016. It has since been updated to include more art from different museums.

Related Contents:

Download 448 Free Art Books from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Puts 400,000 High-Res Images Online & Makes Them Free to Use

Free: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Offer 474 Free Art Books Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness