If you want to immerse yourself in the world of Pablo Picasso, you might start at the Museo Picasso Málaga, located in the artist’s Spanish birthplace. But to understand how his work developed throughout his life, you’ll have to get out of Spain — which is just what Picasso did to accelerate that development in the first place. At the turn of the twentieth century, an ambitious young European painter had to go to Paris, the continent’s art capital. Picasso ended up spending much of his life there, making it the most suitable location for the Musée Picasso, home to the single largest collection of his artworks, from paintings and sculptures to drawings and engravings, as well as an even larger archive of photographs, papers, and correspondence.

Now, you don’t actually have to make the trip to Paris to see these collections, or at least an increasingly large portion of their holdings. As Sarah Kuta reports at Smithsonian.com, thousands of Picasso’s artworks are “now accessible from anywhere with an internet connection, thanks to a new online archive created by the Picasso Museum. The museum has digitized thousands of Picasso’s artworks, essays, poems, interviews and other memorabilia, including items that have never been seen by the public before.” The project began last year, with the digitization of “around 19,000 photos”; if all goes according to plan, the museum will eventually make “an additional 200,000 documents” available online.

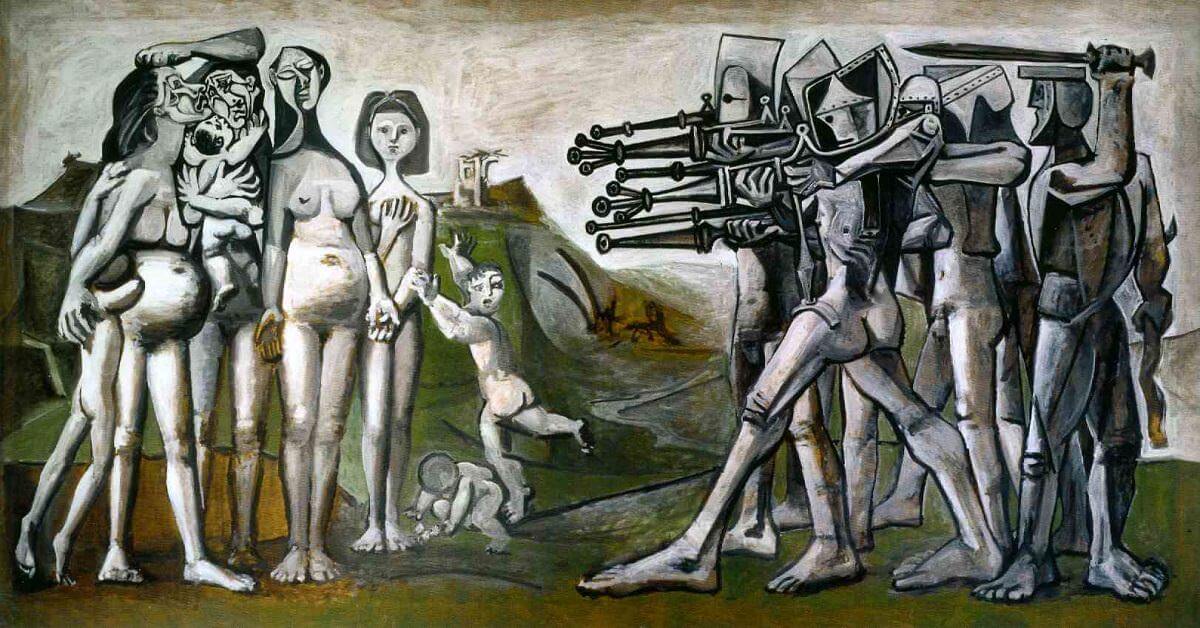

Browse the Musée Picasso’s online archive and you’ll find many works that, assuming you haven’t yet achieved full Picasso immersion, you won’t have seen before: Femme couchée lisant from 1953, seen at the top of the post, for instance, or the earlier Massacre en Corée just above. (Despite living in Korea myself, I had no idea that Picasso painted a Korean War-themed picture, much less an episode of history that took place in the very neighborhood where I used to live.) Not everything is by Picasso, a good deal having been made by artists with whom he was associated, like Man Ray, who took this 1937 photograph of Picasso and his Hispano-Suiza car. You can find much more of interest in the archive’s themed sections, like “Féminin / Masculin” and “Picasso iconophage,” which are navigable only in French — a language that, in any case, every Picassophile should learn. Enter the digital archive here.

via Smithsonian

Related content:

The Mystery of Picasso: Landmark Film of a Legendary Artist at Work, by Henri-Georges Clouzot

A 3D Tour of Picasso’s Guernica

Watch Picasso Create a Masterpiece in Just Five Minutes (1955)

The Louvre’s Entire Collection Goes Online: View and Download 480,00 Works of Art

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.