Maintaining the balance of power among European states has always been a fraught affair, but it was especially so in the years when mercantilism made fragile alliances during the religious wars of the 17th century. This was a time when merchants made excellent diplomats, not only because they traveled extensively and learned foreign tongues and customs, but because they spoke the universal language of trade.

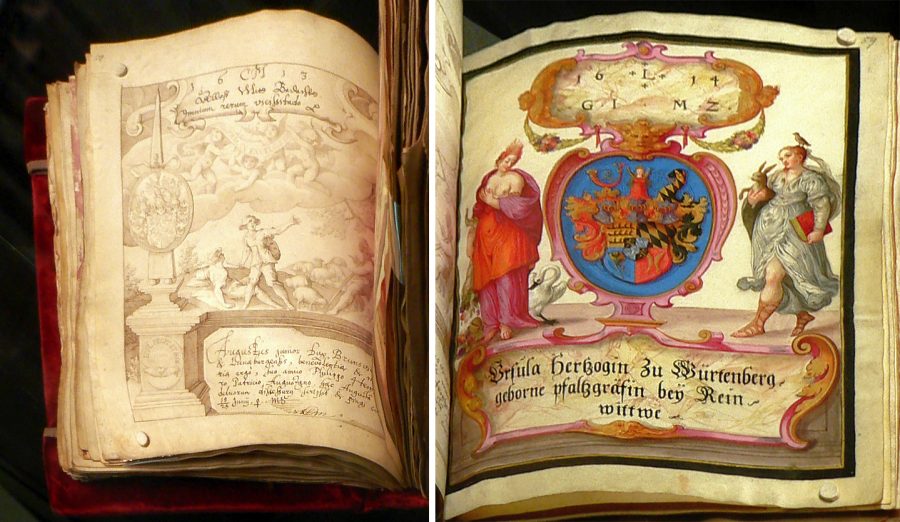

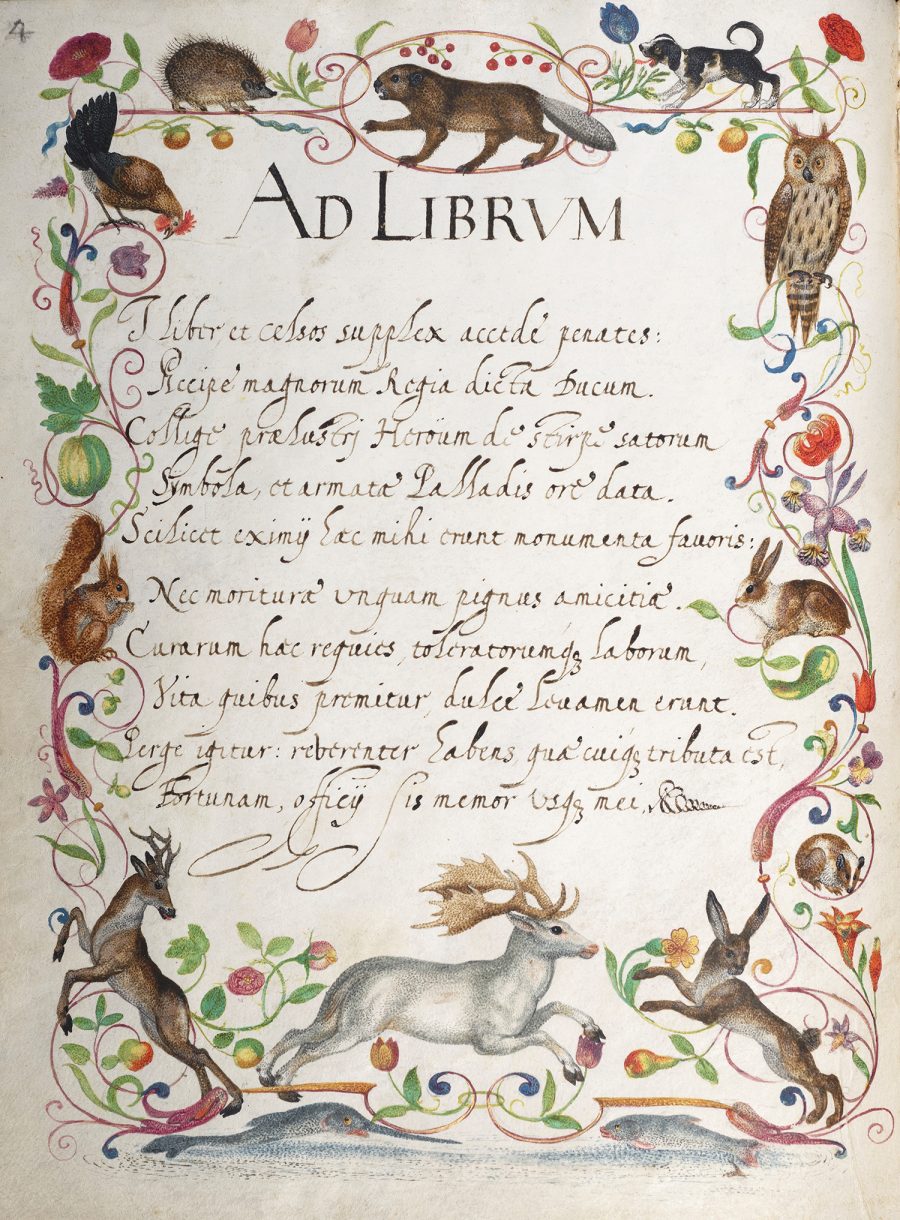

German merchant and diplomat Philipp Hainhofer from Augsburg was such a figure, traveling from court to court to meet with Europe’s renowned dignitaries. As he did so, he would ask them to sign his album amicorum, or “friendship book,” also called a stammbuch. Each signer would then “commission an artist to create a painting accompanying their signatures,” Alison Flood writes at The Guardian.

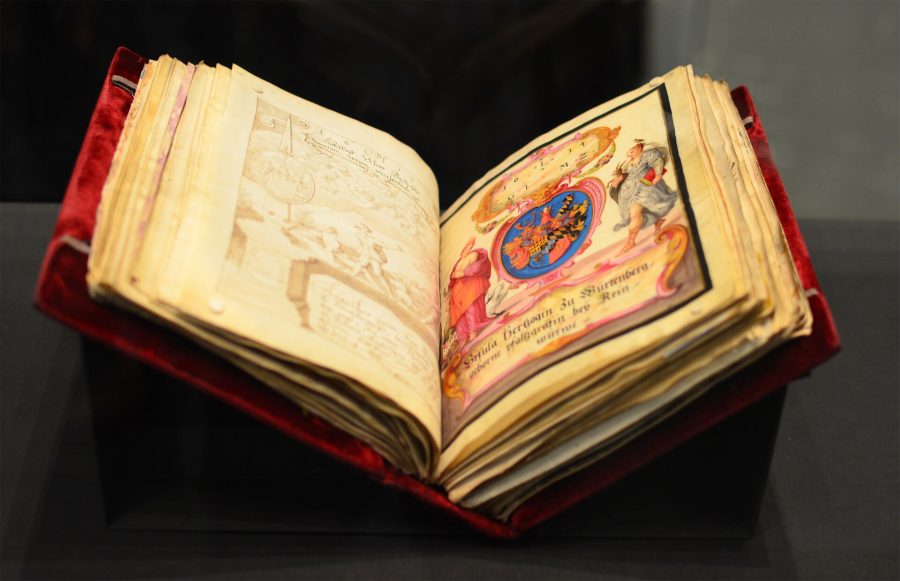

“There are around 100 drawings” in his autograph book, known as the Große Stammbuch, “which took more than 50 years to compile.” After Hainhofer’s death in 1647, his friend August the Younger—who helped collect the hundreds of thousand of books in the Herzog August Bibliothek—tried to acquire the book but failed. Now it has finally landed in the huge library, one of the world’s oldest, almost 400 years later, after a purchase at a private auction this week.

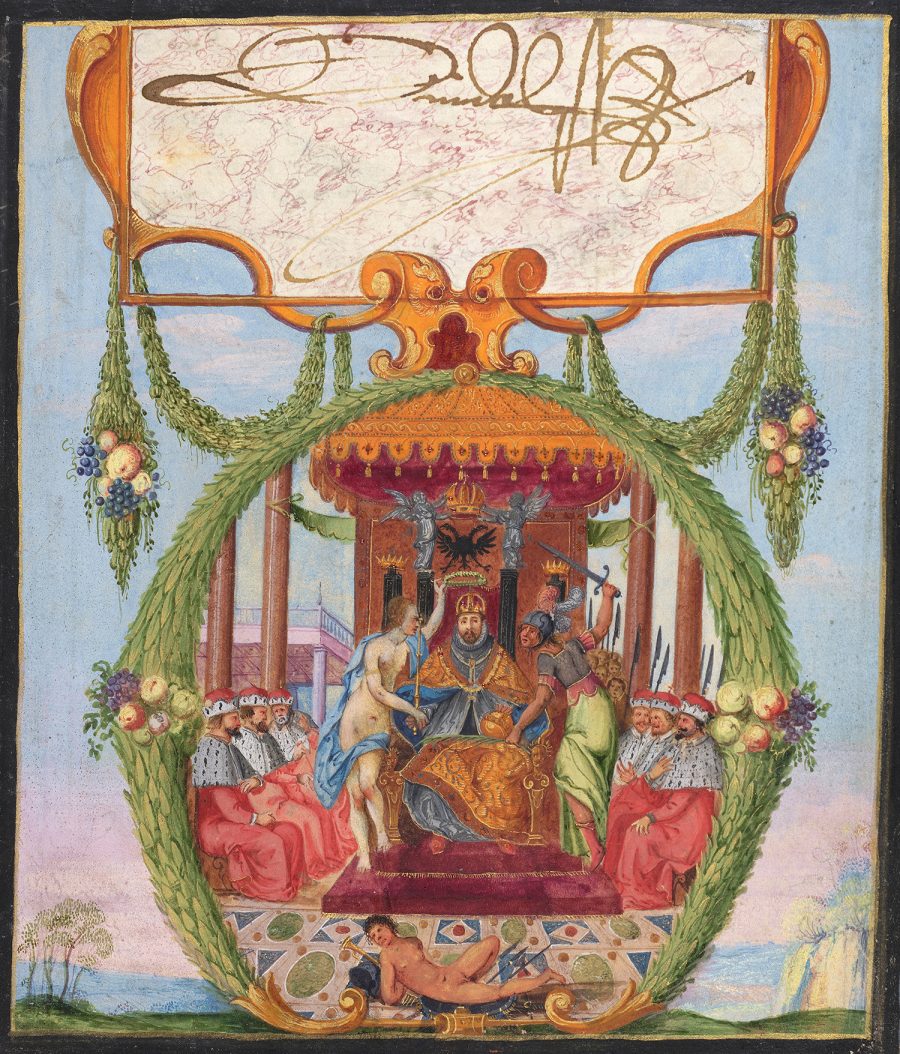

Friendship books were commonly used at the time to record the names of family and friends. Students used them as yearbooks, and Hainhofer began his collection of signatures as a college student. He gradually gained a select clientele as his career advanced. Signatories, the History Blog points out, “include Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, another HRE Matthias, Christian IV of Denmark and Norway, Cosimo II de’Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany…” and many others.

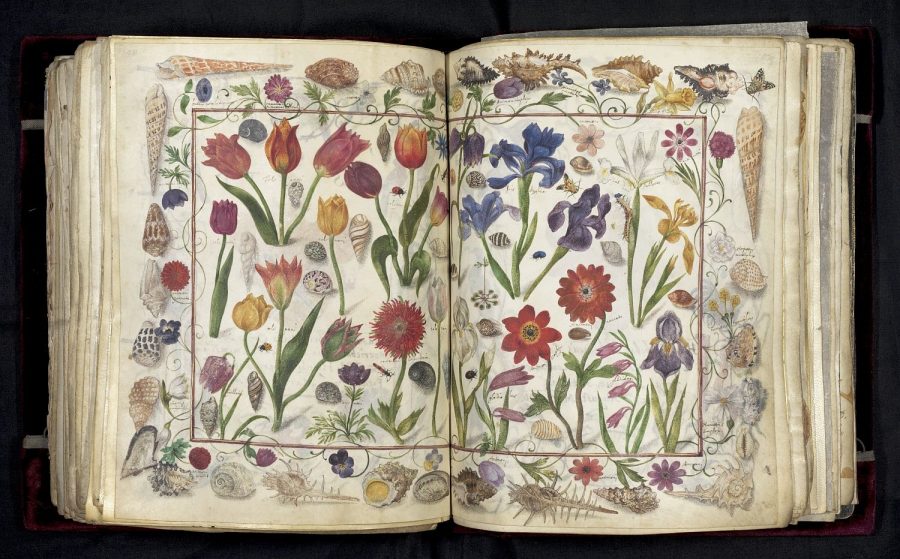

Hainhofer’s Große Stammbuch is, as you can see, a beautiful work of art—or almost 100 collected works of art—in its own right. “The elaborateness of the illustrations directly corresponds to the signatory’s status and rank in society,” as Grace Ebert notes at Colossal. It is also a fascinating record of Early Modern European politics, trade, and diplomacy, a fine art all its own.

via Colossal

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness