There are a few names anyone interested in Japanese woodblock printing today can’t help but hear sooner or later: Utagawa Hiroshige, Katsushika Hokusai, Kitagawa Utamaro, David Bull. That last, you may have guessed, is not the name of an 18th-century Japanese man. In fact, David Bull still walks among us today, especially if we happen to live in the old Asakusa section of Tokyo, where he keeps his woodblock-print studio Mokuhankan.

Born in England and raised in Canada, Bull discovered the world of ukiyo‑e, those Japanese “pictures of the floating world,” in his late twenties. Just a few years after first trying his hand, without formal training, at making his own prints, he moved to the Japanese capital to dedicate himself to the form. Today, on his personal site and Youtube channel, he offers a wealth of English-language resources on the art and craft of the Japanese woodblock print.

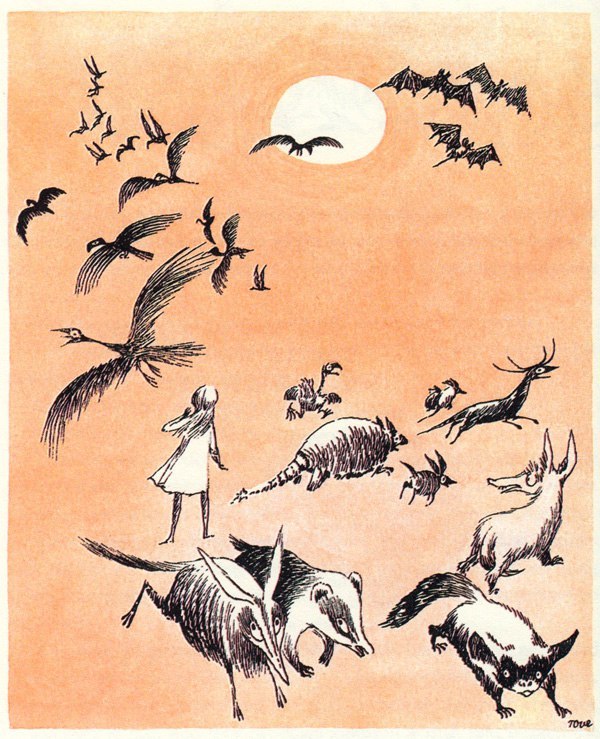

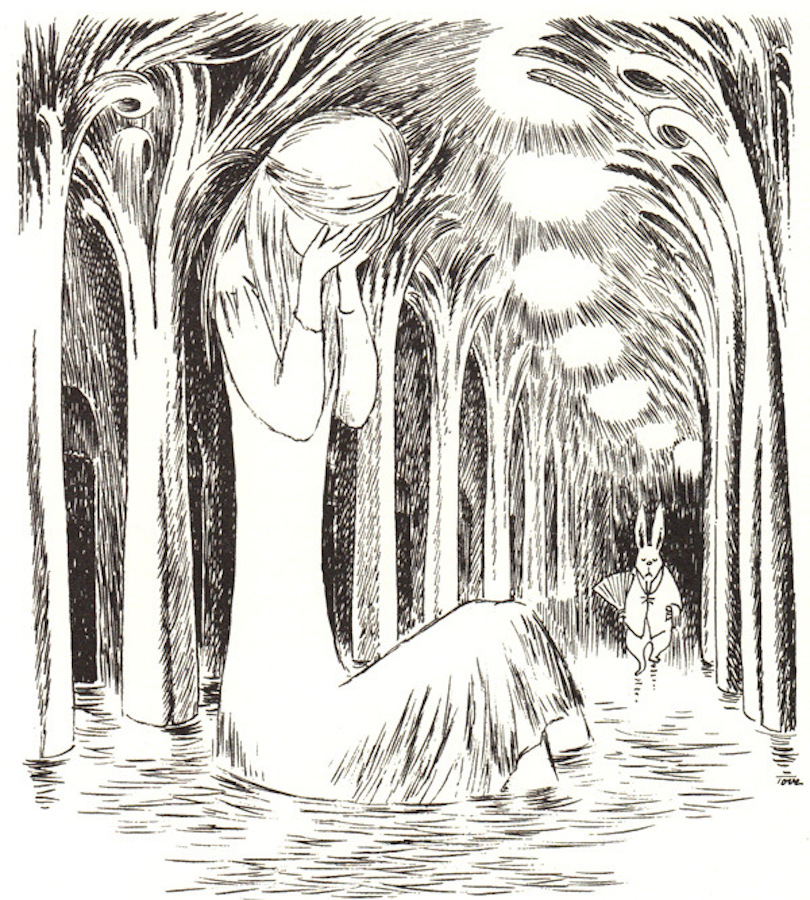

In the video up top, he provides expert commentary on the making of one particular print by a young Mokuhankan printer named Natsuki Suga. The work is broken into ten stages, beginning with the application of the basic orange background color, moving on through the addition of sky blues and tea-field greens (not to mention shadows, shadows, and “more shadows”), all the way through to the final embossing of the title and artist’s name. The result, revealed at the end in a stage-by-stage time lapse, is a vivid and idyllic scene aesthetically balanced between ukiyo‑e tradition and the present-day art styles.

In the video just above, you can see Bull himself provide commentary as he makes a woodblock print of his own — in real time, from start to finish, with no cuts. Originally shot as a live Twitch stream, it shows Bull’s entire process from blank block to completed print, which takes nearly three and a half hours. That may actually seem like a surprisingly short time in which to create a work of art, but then, Bull has been at this for nearly 40 years.

Bull’s experience also comes through in his ability to explain his techniques and tell stories about the Japanese woodblock’s artistic development as well as his own. What may seem like a video of interest only to ukiyo‑e specialists has in fact racked up, as of this writing, more than 1.2 million views on Youtube alone. But then, it isn’t entirely unknown for a soft-spoken artist dedicated to a highly specific form to win a wide audience with his educational productions. “I’m completely certain that Bob Ross hasn’t died,” as one commenter puts it. “He just got a new haircut.”

Related Content:

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

See Classic Japanese Woodblocks Brought Surreally to Life as Animated GIFs

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.