The 2010 documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop seemed to critics both too contrived to be reality and too bizarre to be a hoax: Frenchman-in‑L.A. Thierry Guetta obsessively films graffiti artists and begins pursuing Banksy, who takes over the project and makes a film about Guetta, who, at Banksy’s suggestion, takes up street art, becomes an overnight sensation and — to the somewhat horrified astonishment of Banksy — sells a million dollars worth of his work at his first show as “Mr. Brainwash.”

Worth, in the art world, is a relative term, as Roger Ebert pointed out. So what if Guetta was doing mediocre riffs on Warhol, among others? “Surely Warhol’s message was that Theirry Guetta has an absolute right to call his work art, and sell it for as much as he can.” If he can get away with it, more power to him, but surely there’s a higher authority that really determines what we think of as art? Some honest body of scholars with rigorous standards and generous tastes? Surely there’s something more than sales to determine the value of art?

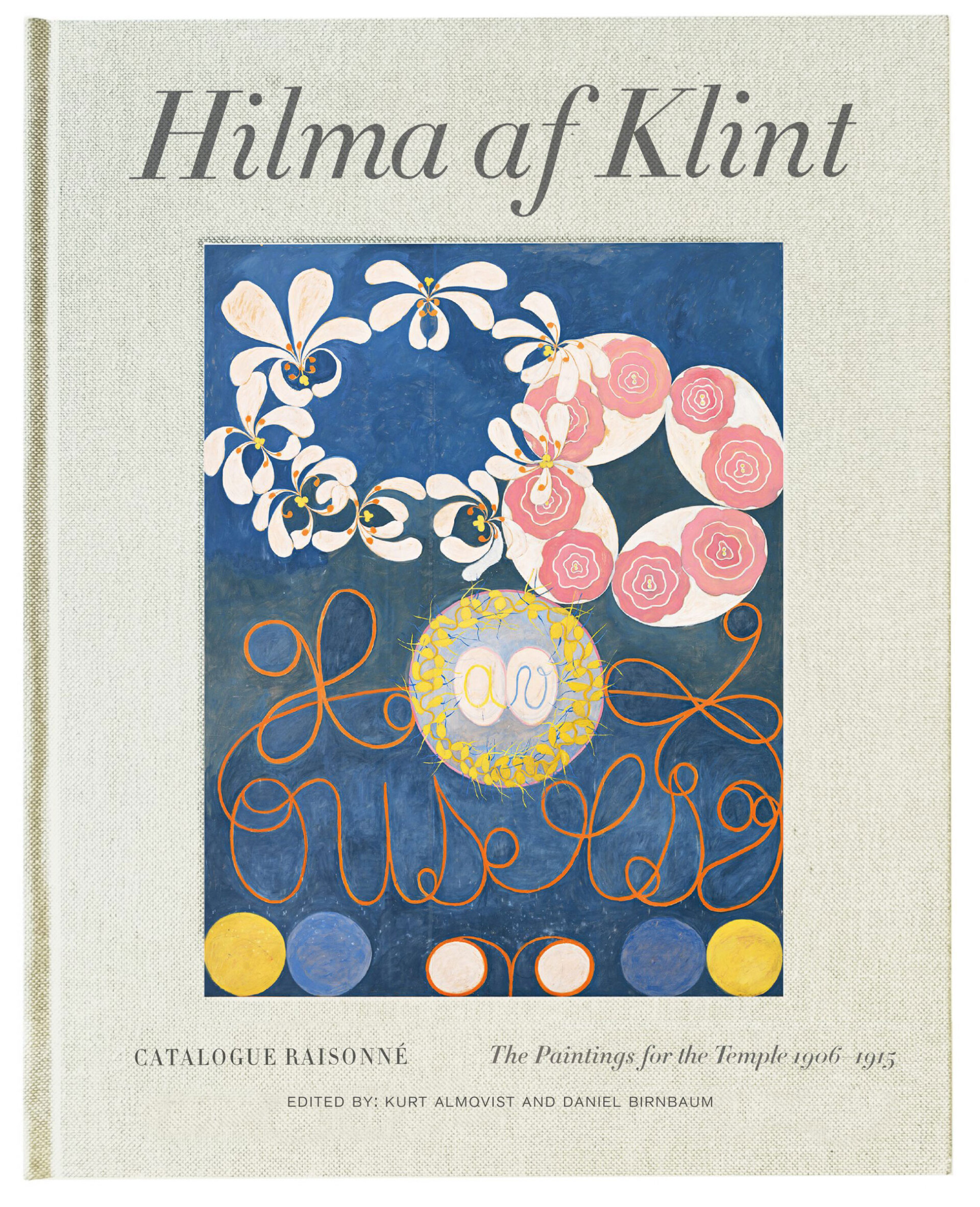

Or maybe, the Vox video above suggests, it really is the eponymous gift shop, whose carefully curated tchotchkes and souvenirs include such collections as “an ear-shaped eraser,” writes Micaela Marini Higgs, “a $495 Versace t‑shirt… and of course, the classics: postcards, mugs, and magnets.” And that’s not to mention all those wonderful books…. Museum gift shops have convinced us that if it sells, it’s art. “Basically, stores are like the ultimate cheat sheet — the more you see a piece of art referenced, the more important it probably is.”

Some visitors even choose to enter through the gift shop, which may, after all, be no stranger than walking through an exhibition the wrong way. Professor of Anthropology Sharon Macdonald describes the retail area of a museum as a show’s final exhibit. Visitors may feel a lack if they can’t conspicuously consume what they have seen. The more they do so, the more they act as advertisements for the art on their tote bags. This is by design, of course.

Museum gift shops not only see themselves as revenue sources — some providing up to a quarter of an institution’s funds — but also as art educators. Store buyers collaborate with curators, who want to give potential visitors a sense of their exhibitions’ main ideas. There is no sinister plot at work, only the reinforcing, through commerce, of the museum’s pre-existing criteria for what qualifies as important art. But you might see a problem — it’s all a bit circular, isn’t it? — and thanks to the “mere-exposure effect,” the circle ripples outward through repeated viewings.

It’s a phenomenon not unlike hearing the same song over and over on the radio and growing to like it through sheer familiarity. Do we “appreciate” art by consuming its likenesses on keychains and mousepads? Maybe we’re also participating in a ritual of commercial consent to the value of certain works over others, mostly unaware of how overpriced gift shop swag meme-ifies art and amplifies cultural values we could think about more critically.

Related Content:

Salvador Dalí’s Tarot Cards, Cookbook & Wine Guide Re-Issued as Beautiful Art Books

Behind the Banksy Stunt: An In-Depth Breakdown of the Artist’s Self-Shredding Painting

Download 584 Free Art Books from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness