Far be it from me, or anyone, to know the future, but several signs point toward another season or two of staying indoors — and maybe putting travel plans on hold again. If, like me, you find yourself itching to get away, maybe to finally make the journey to see the art you’ve only seen in small-scale reproductions, don’t despair just yet. The art is coming to you, in ultra-high resolution, gigapixel images from Google Cultural Institute.

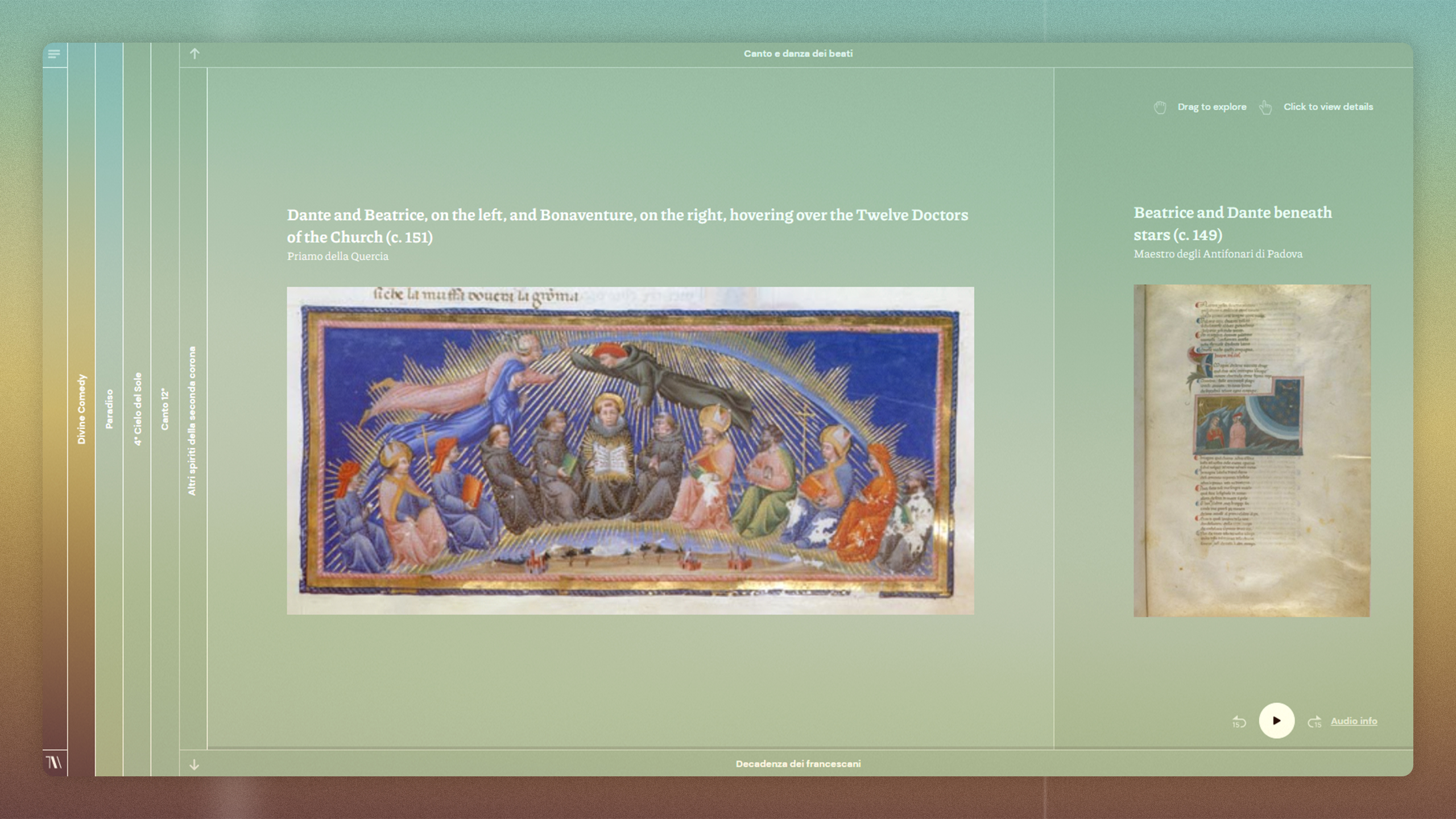

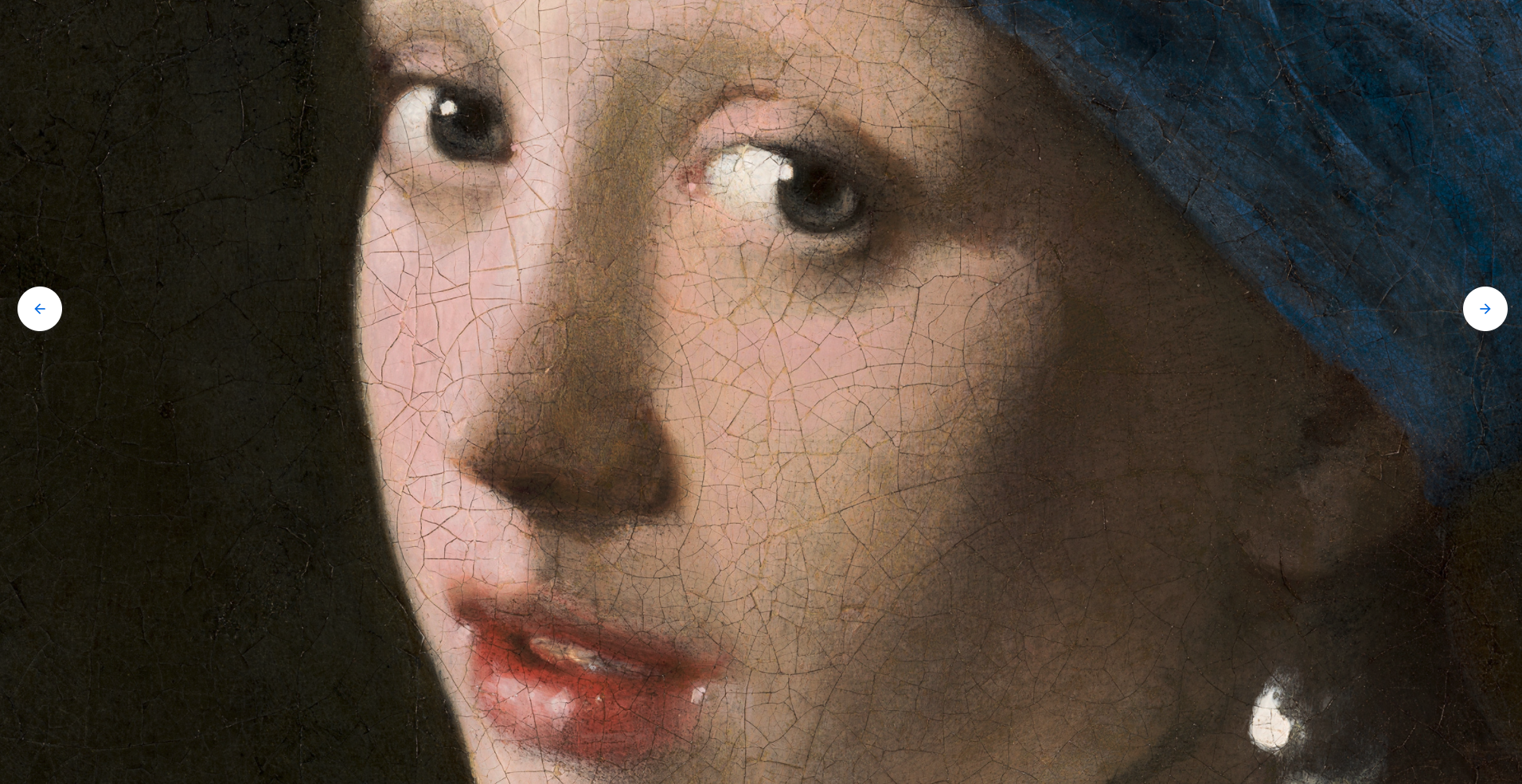

See extraordinary levels of detail in famous works of art like Vermeer’s Girl with the Pearl Earring and Van Gogh’s Starry Night. “So much of the beauty and power of art lives in the details,” writes Google Cultural Institute Engineer Ben St. John.

“You can only fully appreciate the genius of artists like Monet or Van Gogh when you stand so close to a masterpiece that your nose almost touches it.” This kind of intimacy is nearly impossible to achieve in a crowded gallery.

Google’s enormous art photographs are, in some ways, superior to observation with the eye: “Zooming into these images is the closest thing to walking up to the real thing with a magnifying glass.” Even when painted on flat canvases, works of art exist in three dimensions, and there’s still the matter of color reproduction on your screen…. Yet the point remains: there’s no way you’d be able to get as close to Monet or Van Gogh’s work in person unless you were a conservator or maybe a museum guard.

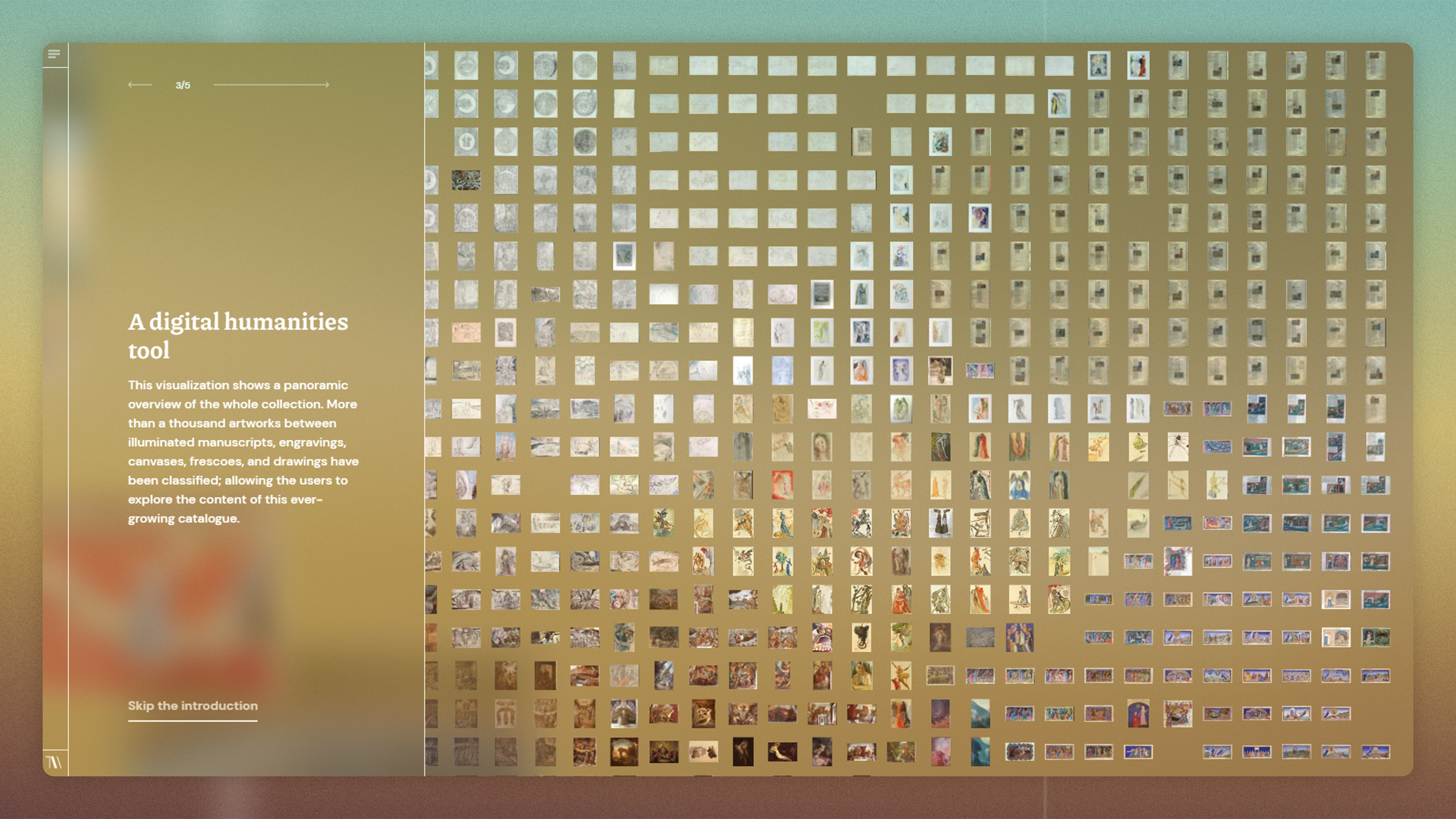

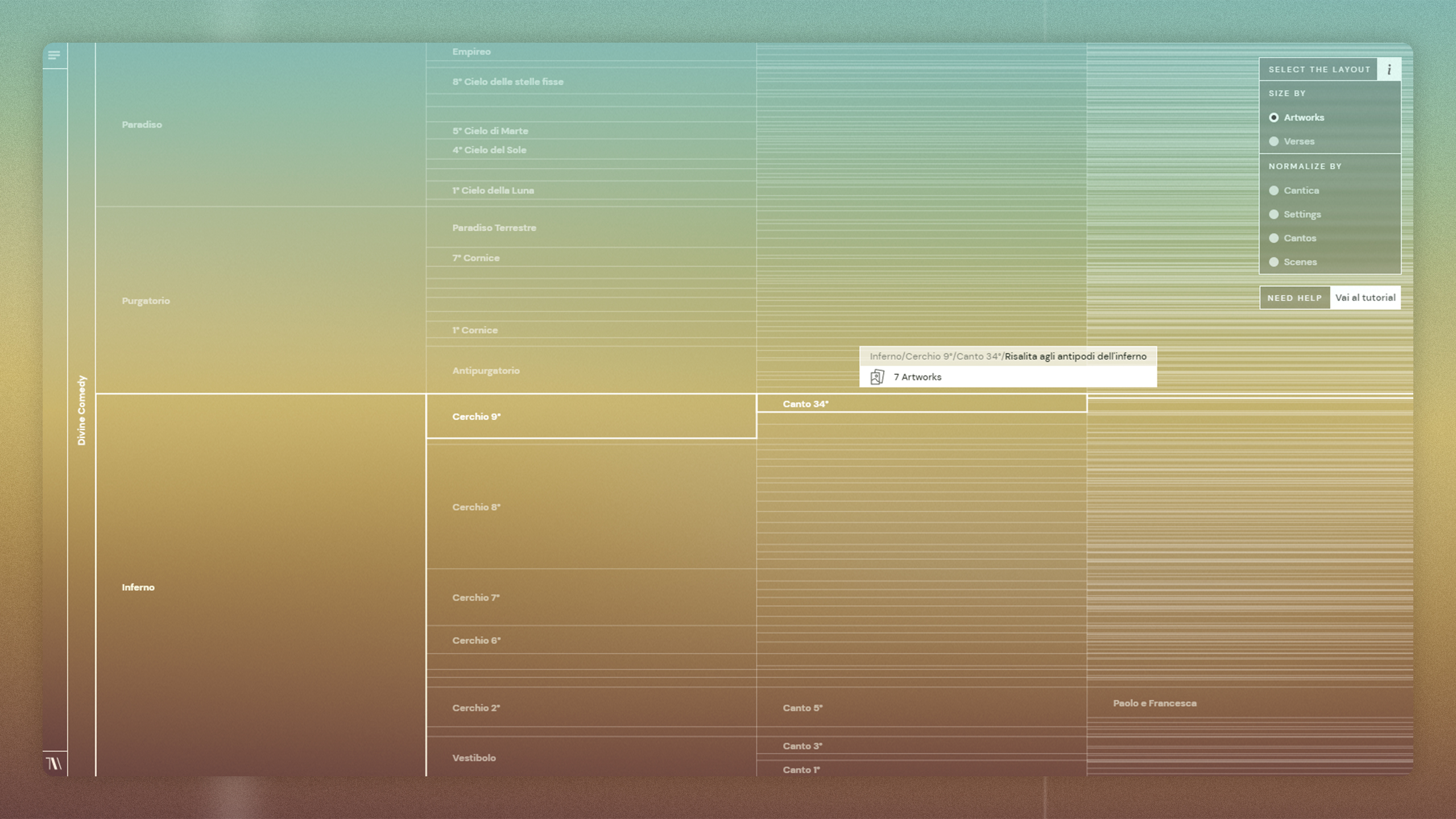

Creating these images has hitherto been an extremely time-consuming affair that required the expert know-how of technicians, a process that has hampered the wide adoption of gigapixel images for the study of art. “In the first five years of the Google Cultural Institute,” Google admits, “we’ve only been able to share about 200 gigapixel images.” The process can now be automated, however, expanding the gallery to 1800+ images and counting, with the invention of a sophisticated machine called the Art Camera:

A robotic system steers the camera automatically from detail to detail, taking hundreds of high resolution close-ups of the painting. To make sure the focus is right on each brush stroke, it’s equipped with a laser and a sonar that—much like a bat—uses high frequency sound to measure the distance of the artwork. Once each detail is captured, our software takes the thousands of close-up shots and, like a jigsaw, stitches the pieces together into one single image.

The technological breakthrough inarguably enhances our experience of art, whether we ever get to see these works in person, and it preserves a cultural legacy for posterity. “Many of the works of our greatest artists are fragile and sensitive to light and humidity,” Google Arts & Culture notes. “With the Art Camera, museums can share these priceless works with the global public while they’re ensuring they’re preserved for future generations.”

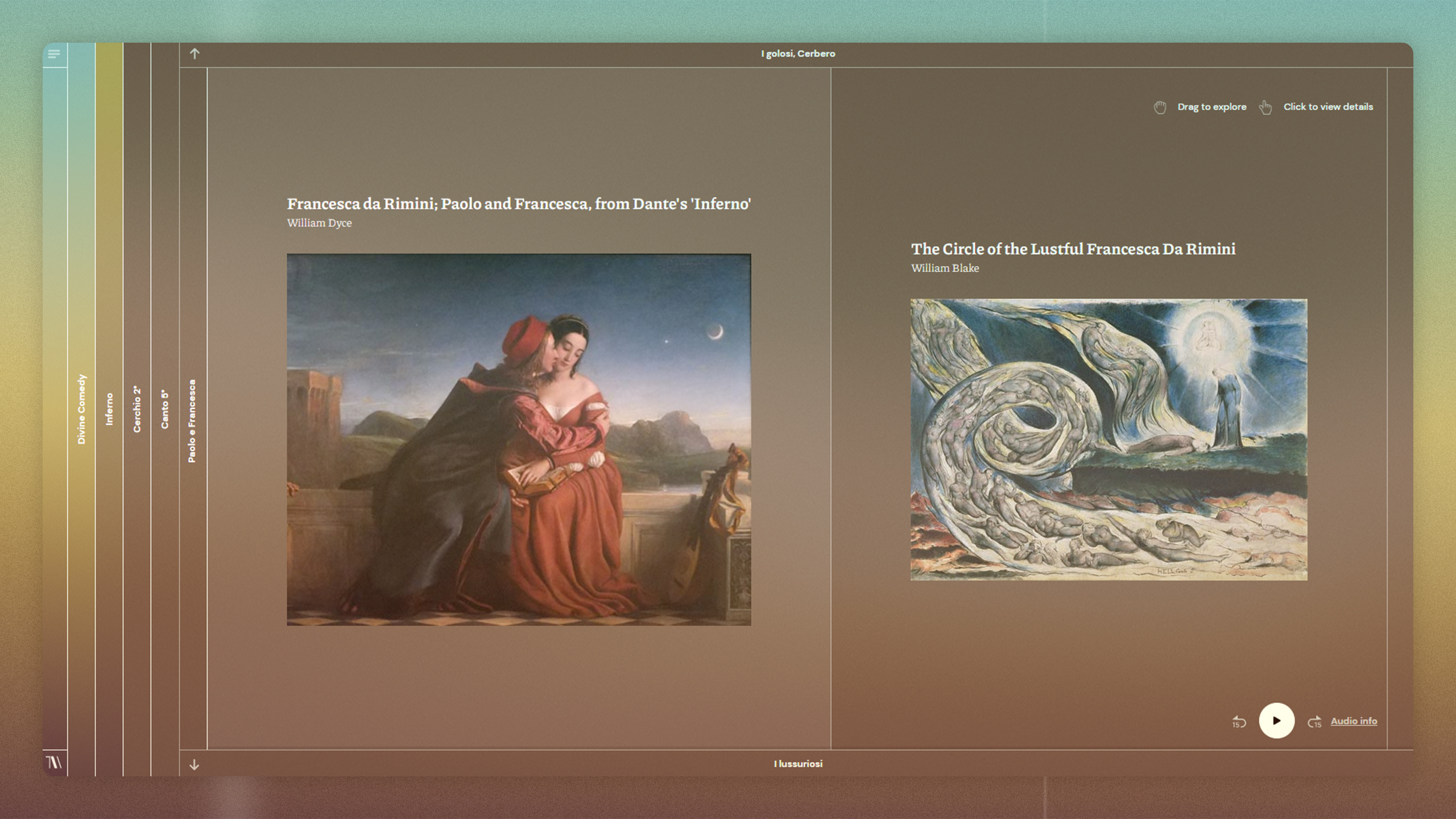

They are preserved in multiple views that give the illusion of a three-dimensional experience, including a “street view” option that places viewers inside the gallery and an augmented reality app called Art Projector that “lets you see how artworks look in real size in front of you.” Viewing art this way goes miles beyond my art history education spent staring at the pages of Janson’s History of Art, trying to imagine what it would be like if I could actually see what was happening on the canvas.

Projects like Google Arts & Culture offer an entirely new kind of art education by digitally conserving hundreds of artworks that don’t tend to appear in textbooks, surveys, or museum gift shops. Works, for example, like Joos van Craesbeeck’s Hieronymus Bosch-influenced The Temptation of Saint Anthony, which show how seriously Bosch’s contemporaries and followers took his medieval “diableries”; and Kristian Zahrtmann’s 1894 painting The Mysterious Wedding in Pistoia. “Idolised” in his time, Zahrtmann “managed to rejuvenate Danish painting in the early 20th century” then sank into obscurity. His work is now “the object of renewed interest — at the dawn of another new century.”

While I hope our experience of art does not become primarily virtual, we can be grateful for the opportunity to see — in ways we never could before — the up-close handiwork of artists who can feel so far away from us even in the best of times. Enter the collection here.

Related Content:

Google Puts Over 57,000 Works of Art on the Web

The Art Institute of Chicago Puts 44,000+ Works of Art Online: View Them in High Resolution

Download 586 Free Art Books from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness