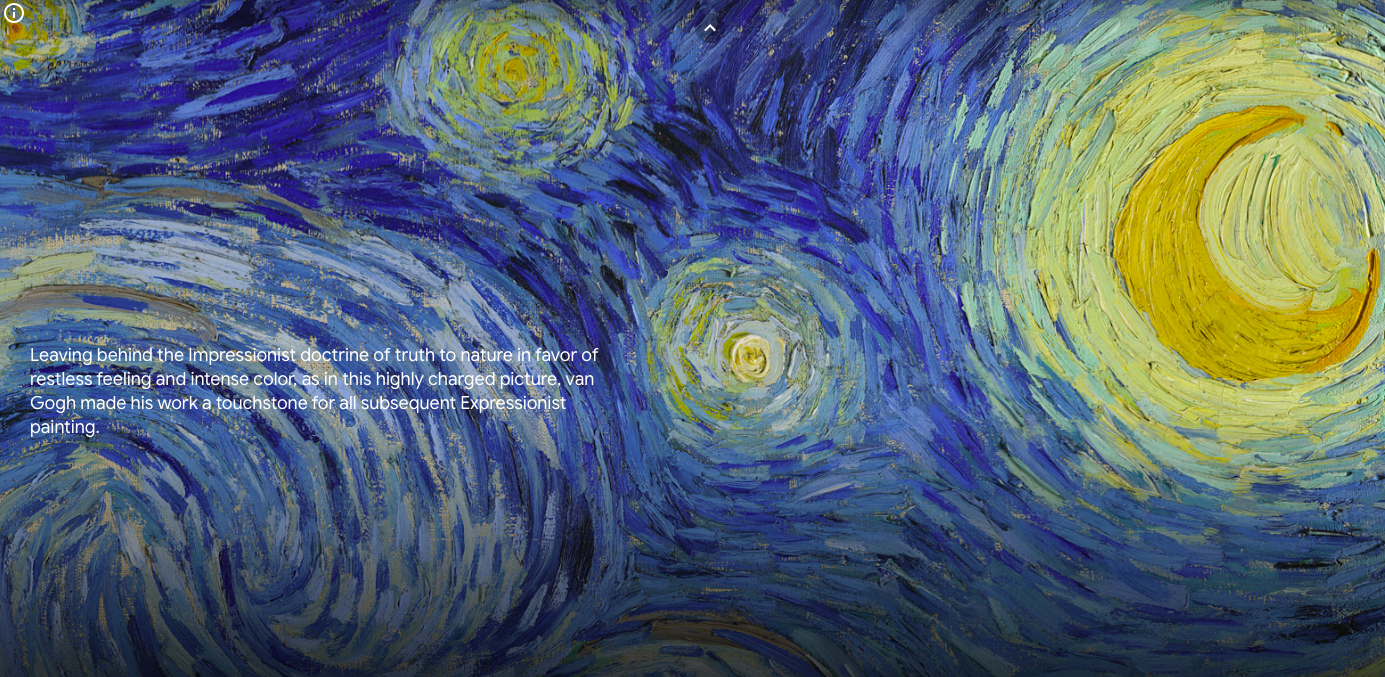

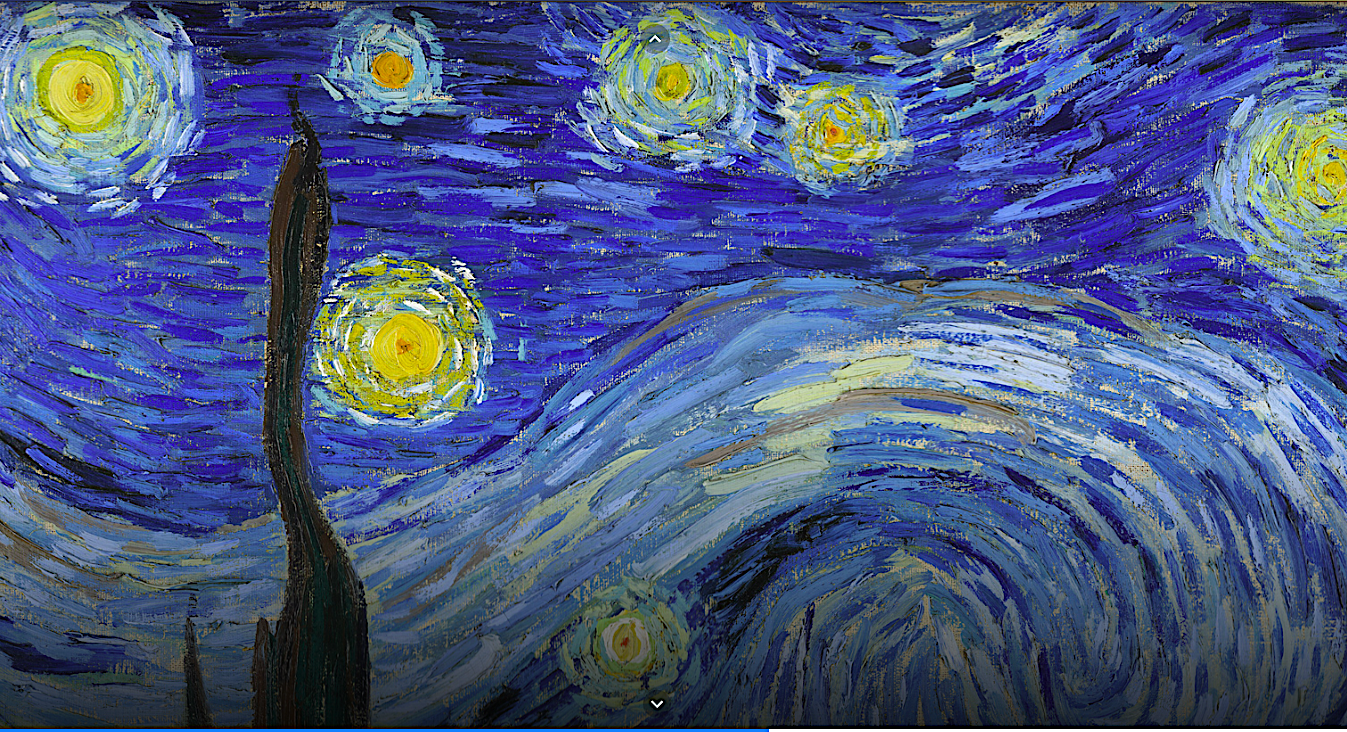

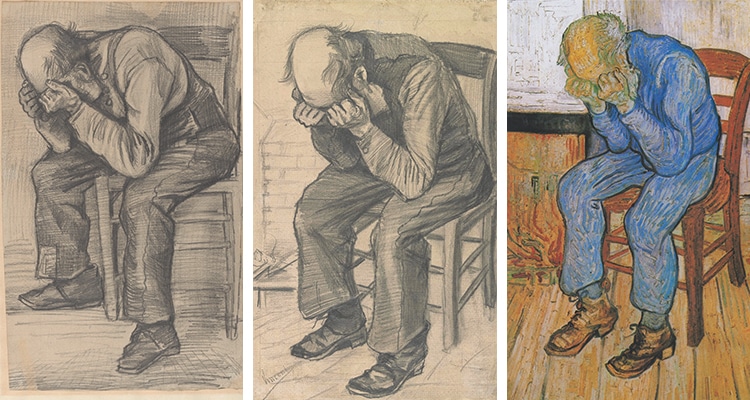

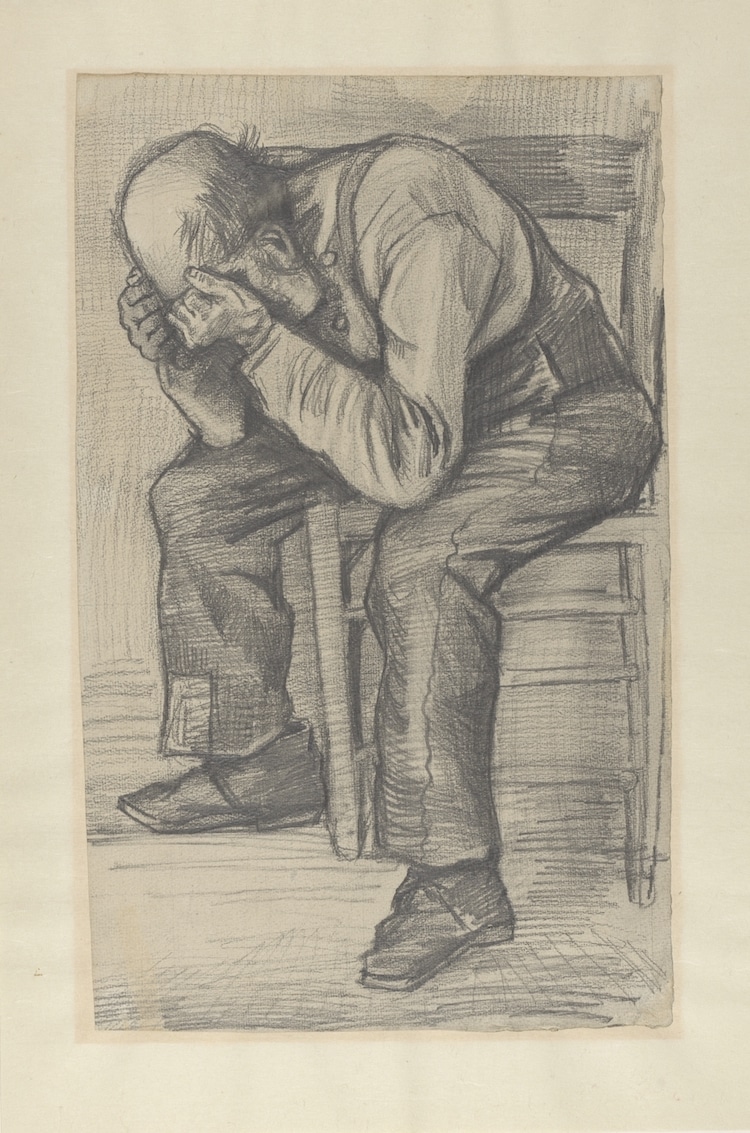

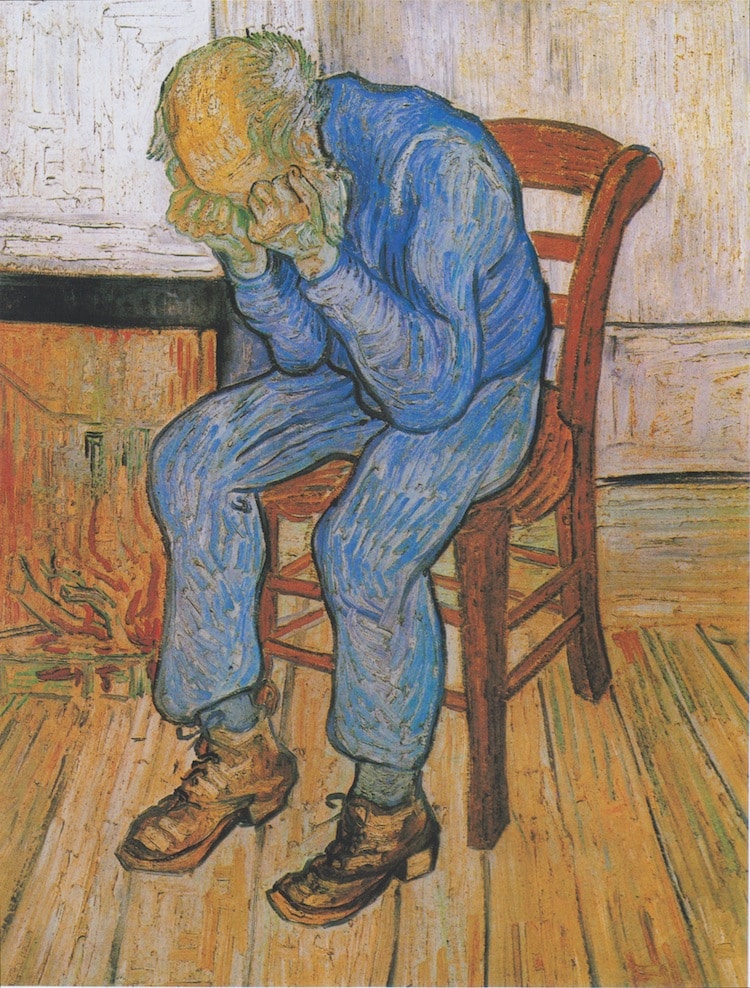

Having been dead for more than 130 years now, Vincent van Gogh seldom comes up with a new piece of work. But when he does, you can be sure it will draw the art world’s attention as few works by living artists could. Such has been the case with the newly discovered Study for Worn Out, an 1882 sketch that recently came into possession of the Van Gogh Museum, according to Margherita Cole at My Modern Met, “when a Dutch family requested that specialists take a look at their unsigned drawing.” The figure in the drawing strongly resembles the one in van Gogh’s 1890 painting At Eternity’s Gate. But it took the experts at the museum to determine that the artist was none other than van Gogh himself.

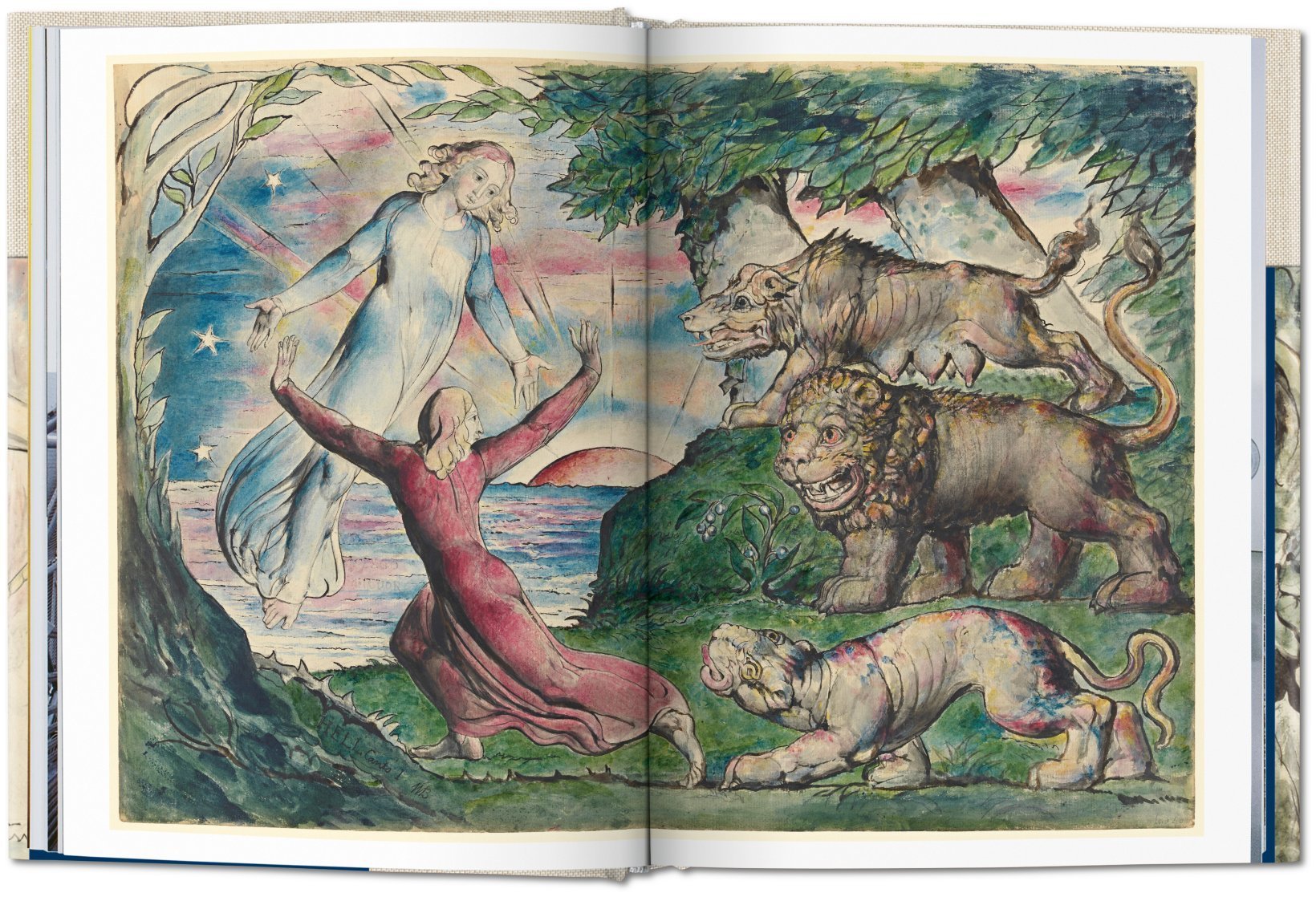

“Today and yesterday I drew two figures of an old man with his elbows on his knees and his head in his hands,” wrote the 29-year-old van Gogh to his brother in a letter from 1882. “What a fine sight an old working man makes, in his patched bombazine suit with his bald head.” The immediate fruit of these labors was the pencil drawing Worn Out, for which “the artist employed one of his favorite models, an elderly man named Adrianus Jacobus Zuyderland who boasted distinctive sideburns (and who appears in at least 40 of van Gogh’s sketches from this period).” So writes Smithsonian.com’s Nora McGreevy, who adds that van Gogh revisited the work to adapt it as a painting “just two months before his death” in an asylum near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

“In drawings like these,” says the Van Gogh Museum, “the artist not only displayed his sympathy for the socially disadvantaged — no way inferior in his eyes to the well-to-do bourgeoisie — he actively called attention to them too.” Another aim with Worn Out, adds McGreevy, was “to seek employment at a British publication, but he either failed to follow through on this idea or had his work rejected.” This would have counted as just another seeming instance of failure, the likes of which characterized the painter’s short life. Little could he, his correspondents, or his models have imagined that his works would one day become some of the most famous in the world — and certainly not that one of his sketches would go on to be enshrined well over a century later, as it has been since last Friday at the museum that bears his name.

via My Modern Met

Related Content:

Download Hundreds of Van Gogh Paintings, Sketches & Letters in High Resolution

Experience the Van Gogh Museum in 4K Resolution: A Video Tour in Seven Parts

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.