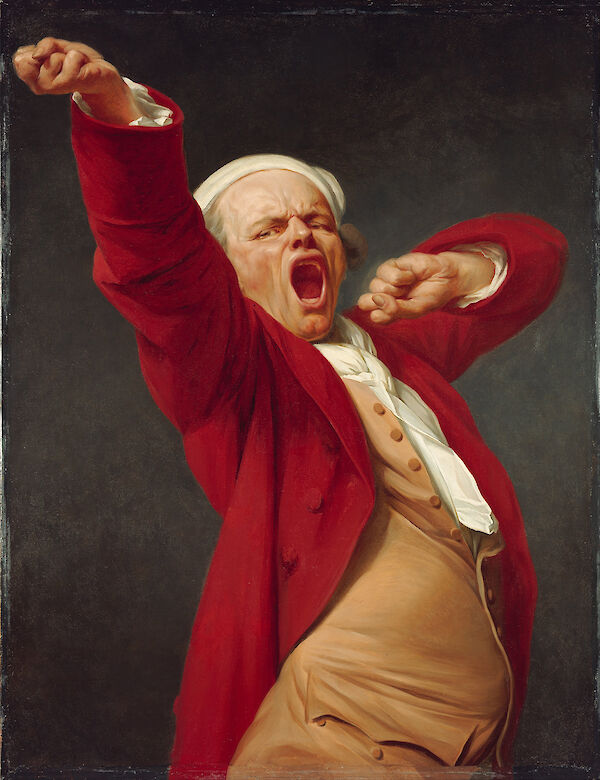

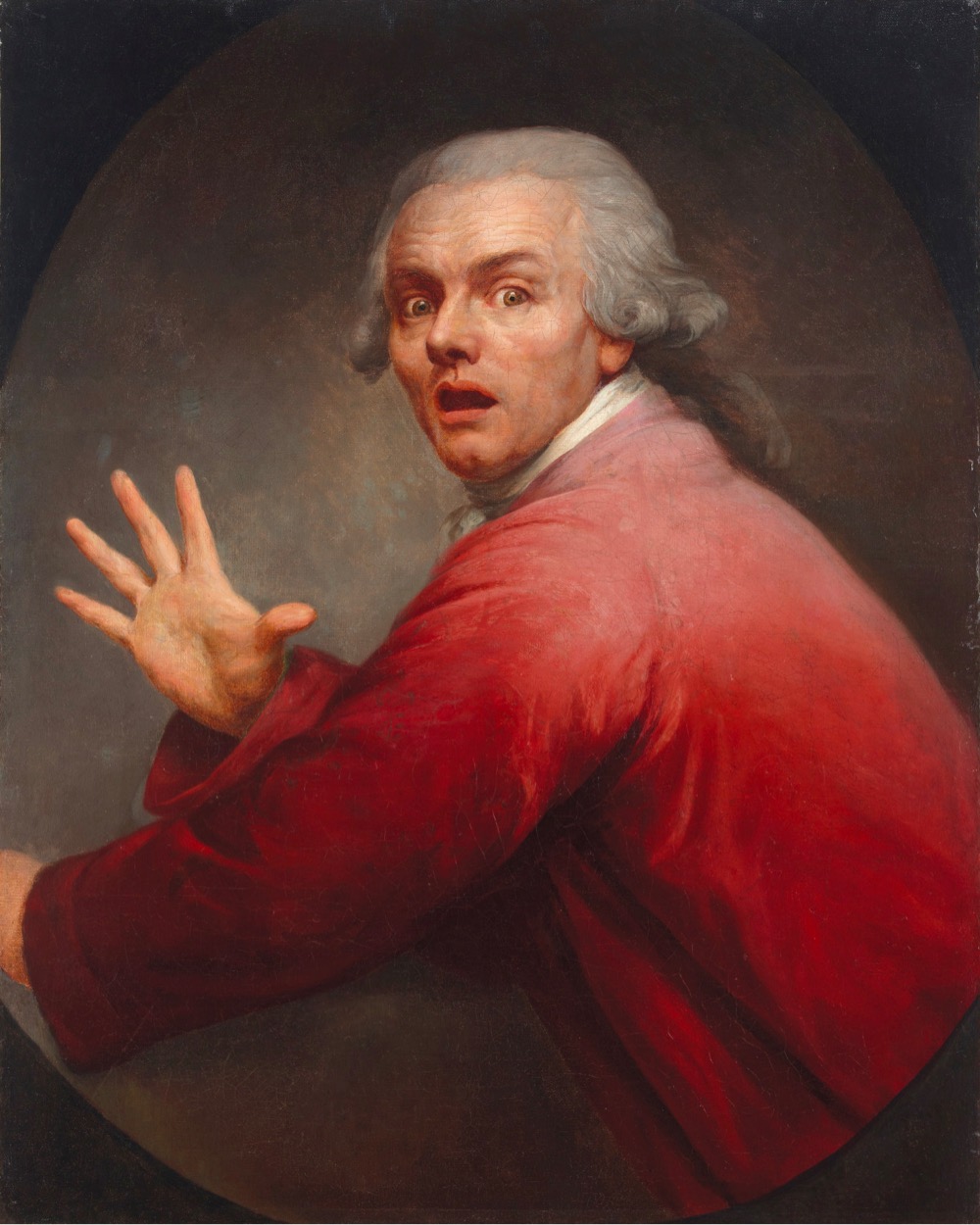

In this short video, Romanian animator Sebastian Cosor brings together two haunting works from different times and different media: The Scream, by Norwegian Expressionist painter Edvard Munch (1863–1944), and “The Great Gig in the Sky,” by the British rock band Pink Floyd.

Munch painted the first of four versions of The Scream in 1893. He later wrote a poem describing the apocalyptic vision behind it:

I was walking along the road with two Friends

the Sun was setting — the Sky turned a bloody red

And I felt a whiff of Melancholy — I stood

Still, deathly tired — over the blue-black

Fjord and City hung Blood and Tongues of Fire

My Friends walked on — I remained behind

– shivering with anxiety — I felt the Great Scream in Nature

Munch’s horrific Great Scream in Nature is combined in the video with Floyd’s otherworldly “The Great Gig in the Sky,” one of the signature pieces from the band’s 1973 masterpiece, Dark Side of the Moon. The vocals on “The Great Gig” were performed by an unknown young songwriter and session singer named Clare Torry.

Torry had been invited by producer Alan Parsons to come to Abbey Road Studios and improvise over a haunting piano chord progression by Richard Wright, on a track that was tentatively called “The Mortality Sequence.” The 25-year-old singer was given very little direction from the band. “Clare came into the studio one day,” said bassist Roger Waters in a 2003 Rolling Stone interview, “and we said, ‘There’s no lyrics. It’s about dying — have a bit of a sing on that, girl.’ ”

Forty-two years later, that “bit of a sing” can still send a shiver down anyone’s spine. For more on the making of “The Great Gig in the Sky,” and Torry’s amazing contribution, see the clip below to hear Torry’s story in her own words.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. Or follow our posts on Threads, Facebook, BlueSky or Mastodon.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

30,000 Works of Art by Edvard Munch & Other Artists Put Online by Norway’s National Museum of Art

Explore 7,600 Works of Art by Edvard Munch: They’re Now Digitized and Free Online

Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour Sings Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18

The Night Frank Zappa Jammed With Pink Floyd … and Captain Beefheart Too (Belgium, 1969)