In the National Gallery there hangs a portrait of an unknown woman, painted by an unknown artist around 1470 somewhere in southwestern Germany. This may sound like an artwork of little note, but it does boast one highly conspicuous mark of distinction: a housefly. It’s not that the portraitist was in such thrall to realism that he included an insect that happened to drop into the sitting; at first glance, the fly looks as if it belongs to our reality, and has alighted on the canvas itself. Why would a painter, presumably commissioned at the considerable expense of the sitter’s family, include such a seemingly bizarre detail? National Gallery curator Francesca Whitlum-Cooper offers answers in the video below.

“It’s a joke,” says Whitlum-Cooper. “And it’s a joke that works on different levels, because on the one hand, the fly has been tricked into thinking this is a real headdress,” fooled by the painter’s mastery of that most difficult color for light and shadow, white.

“But obviously there’s a double joke, because we, looking at it, think, ‘Oh my gosh, there’s a fly on that painting!’ ” It is our very instinct to shoo the bug away that tells us “we’ve been duped, because actually, everything here is two-dimensional. This is just paint. And the skill of the artist is that they’ve been able to take that paint, and brush, and a bit of wood, and conjure it into something that feels so lifelike, we do believe — even just for a second — that’s a fly sitting on that picture.”

Five centuries later the joke still works, though it could well be more than a joke. One theory put forth here and there in the comments holds that the fly functions as a reminder of impermanence, of decay, of mortality. If so, it suggests that the subject of this portrait may already have been dead by the time of its painting, a notion supported by the symbolic weight of the forget-me-nots in her hand. (One commenter even argues that the artist is none other than the famed Albrecht Dürer, and that the woman depicted is his late mother.) Though it may not rank among the great works of art, this mysterious image nevertheless shares with them the quality of multivalence. The fly could be a gag, and it could be a memento mori — but why not both?

Related Content:

A Restored Vermeer Painting Reveals a Portrait of a Cupid Hidden for Over 350 Years

What Made Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus a Revolutionary Painting

The Genius of Albrecht Dürer Revealed in Four Self-Portraits

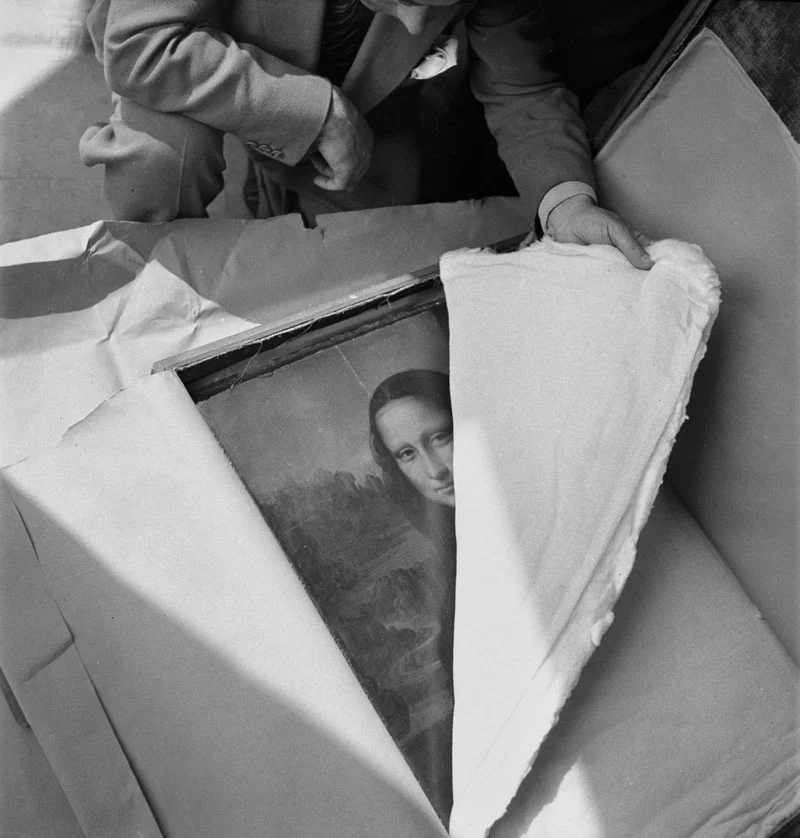

What Makes the Mona Lisa a Great Painting: A Deep Dive

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.