“The idea of the unrecognized genius slaving away in a garret is a deliciously foolish one,” says artist and critic Rene Ricard, as portrayed by Michael Wincott, in Julian Schnabel’s Basquiat. “We must credit the life of Vincent Van Gogh for really sending this myth into orbit.” And “no one wants to be part of a generation that ignores another Van Gogh. In this town, one is at the mercy of the recognition factor.” The town to which he refers is, of course, New York, in which the titular Jean-Michel Basquiat lived the entirety of his short life — and created the body of work that has continued not just to appreciate enormously in value, but to command the attention of all who so much as glimpse it.

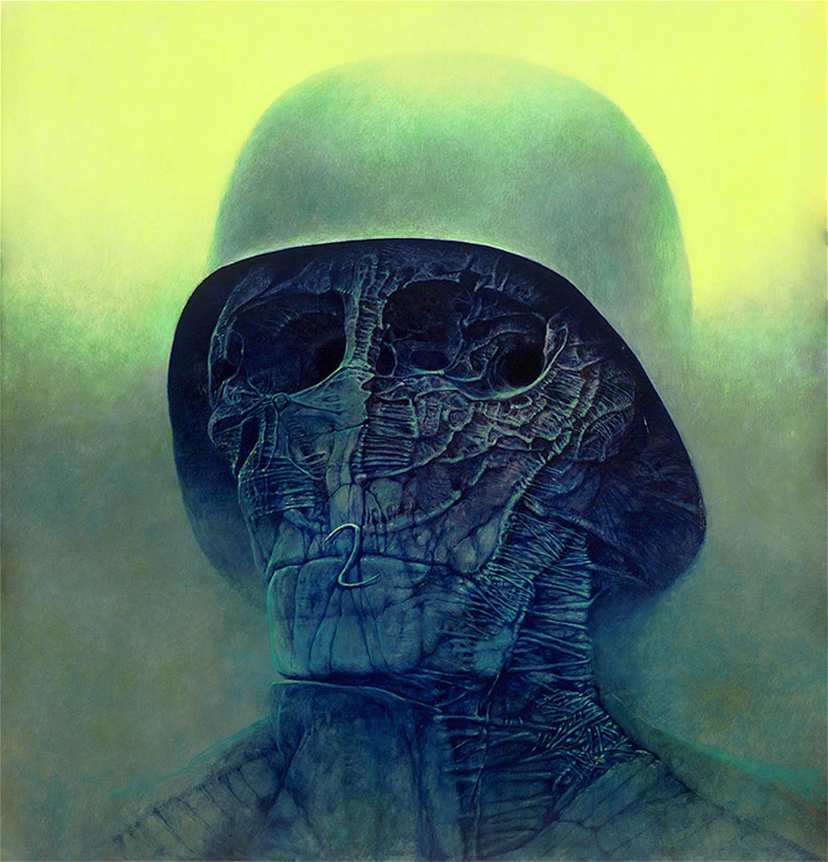

As a film Basquiat has much to recommend it, not least David Bowie’s appearance as Andy Warhol. But as one would expect from a biopic about an artist directed by one of his contemporaries, it takes a subjective view of Basquiat’s life and career. “The Revolutionary Paintings of Jean-Michel Basquiat,” the video essay by Youtube Blind Dweller above, adheres more closely to the historical record, telling the story of how his wild imagination spurred him on to become the hottest phenomenon on the New York art scene of the nineteen-eighties. By the middle of that decade, the young Brooklynite who’d once lived on the street after dropping out of school found himself making over a million dollars per year with his art.

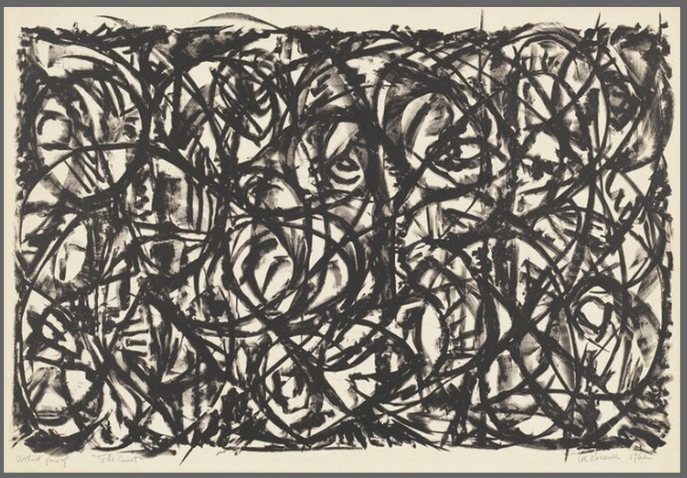

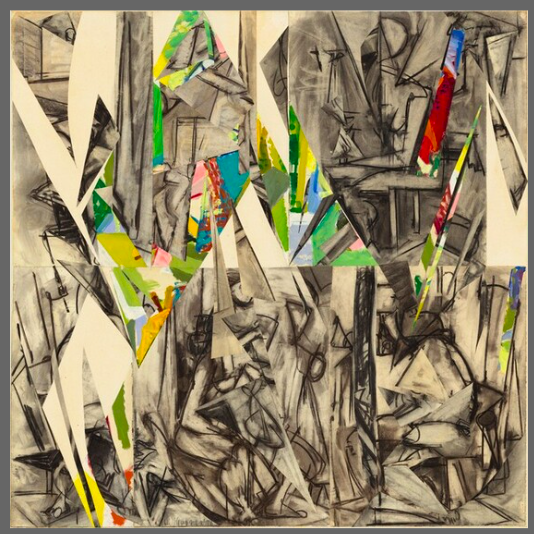

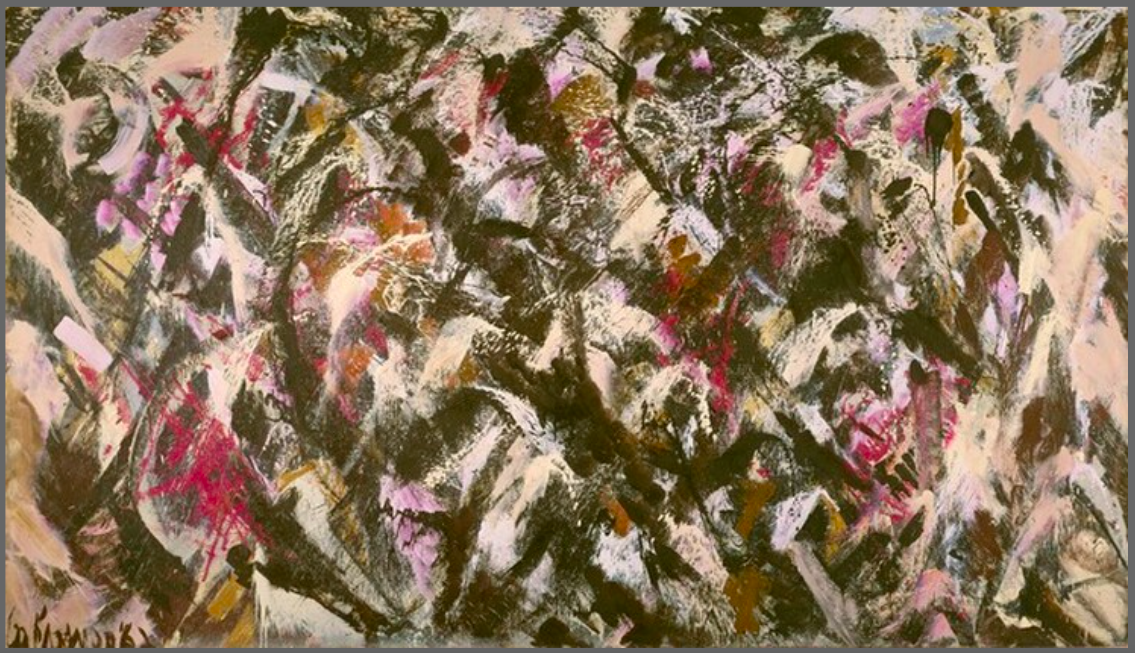

At that time Basquiat “had collectors knocking on his door nearly every day demanding art from him, yet simultaneously asking for specific colors or imagery to match their furniture,” which resulted in “him slamming the door in a lot of collectors’ faces.” He refused to produce art to order, consumed as he was with his own interests — the law, sainthood, African culture, black American history, the built environment of New York City — and their incorporation into his work. He also possessed a keen sense of how to maintain a tantalizing distance between himself and his public, for instance by deliberately crossing out text in his paintings on the theory that “when a word is more obscured, the more likely an observer will be drawn to it.”

This would have been evident to Warhol, himself no incompetent when it came to audience management. His association with Basquiat secured both of their places in the zeitgeist of eighties America, but his death in 1987 marked, for his young protégé, the beginning of the end. “He began dissociating himself from his downtown past, attending more parties reserved for the super-rich, and becoming increasingly obsessed with the idea of being accepted by certain crowds,” says Blind Dweller, and his final heroin overdose occurred the very next year. Basquiat is remembered as both beneficiary and victim of the phenomenon to which we refer (now almost always positively) as hype — countless cycles of which have since done nothing to diminish the vitality exuded by his most striking paintings.

Related content:

The Story of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Rise in the 1980s Art World Gets Told in a New Graphic Novel

The Odd Couple: Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, 1986

When Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party Brought Klaus Nomi, Blondie & Basquiat to Public Access TV (1978–82)

When David Bowie Played Andy Warhol in Julian Schnabel’s Film, Basquiat

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.