We’ve had fun at the expense of the multi-hyphenate: i.e. “I’m an actor-slash-drummer-slash-makeup-artist-slash-brand-ambassador,” etc…. And, fair enough. Few people are good enough at their one job to reasonably excel at two or three, right? But then again, we live in the kind of hyperspecialized world Henry Ford could only dream of, and consider ourselves highly favored if we’re allowed to be just the one thing long enough to retire and do nothing.

What if we could have multiple identities without being thought of as unserious, eccentric, or mentally ill?

Discussions of Syd Barrett, Pink Floyd’s founding singer and guitarist, never pass without reference to his mental illness and abrupt disappearance from the stage. But they also rarely engage with Barrett as an artist post-Pink Floyd: namely, his two underrated solo albums; and his output as a painter, the medium in which he began his career and to which he returned for the last thirty years of his life.

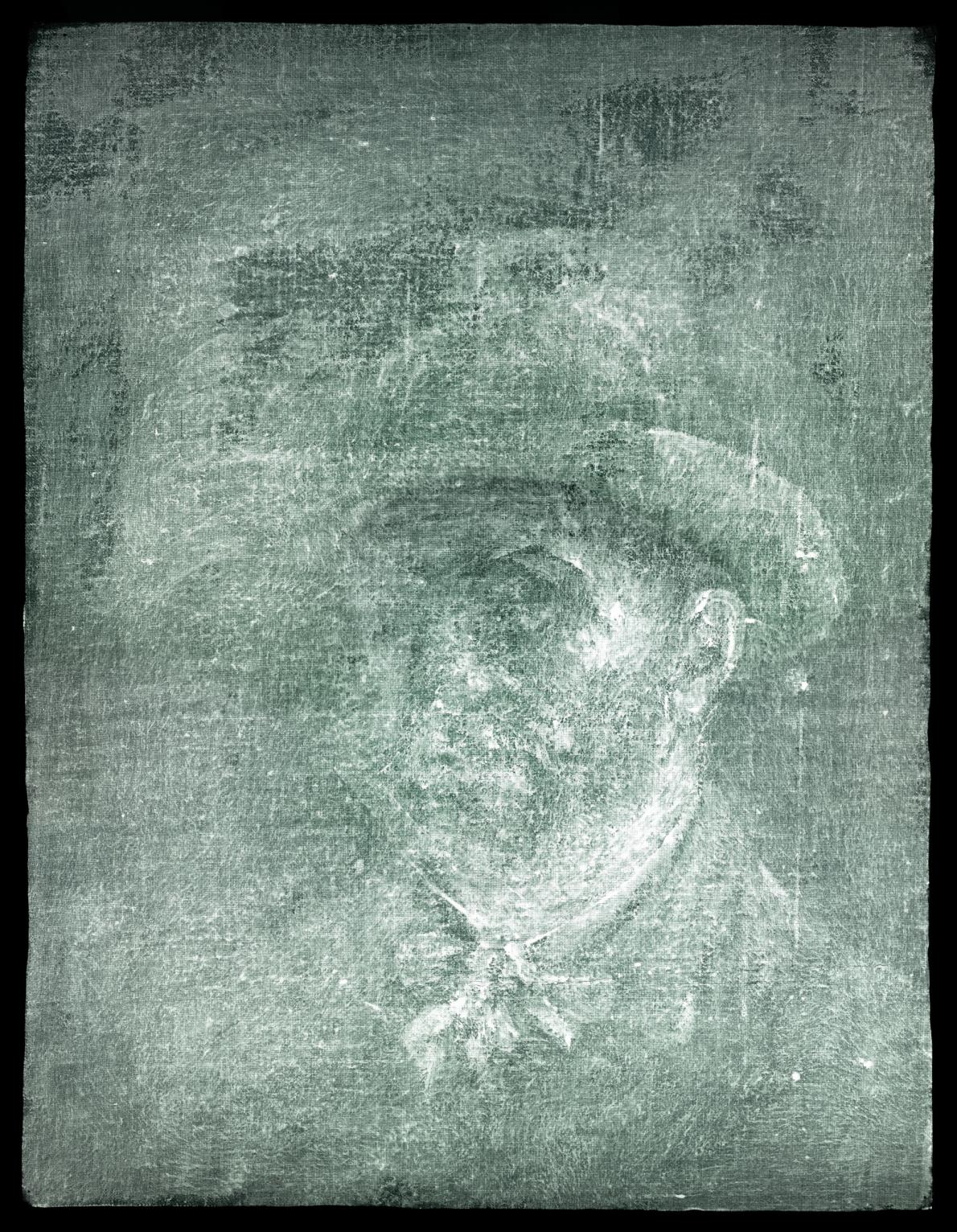

If Barrett were allowed a role other than crazy diamond (a role, we must allow, assigned to him by his former bandmates), we might see more of his work in gallery collections and exhibitions. One cannot say this about every famous musician who paints. For Barrett, art was not a hobby, and it called to him before music. It was in his student days at Cambridgeshire College of Arts and Technology that he met David Gilmour. From Cambridge he moved to Camberwell College of Arts in London and began to produce and exhibit mature student work (see here).

Barrett’s work “shows some of the advantages of an art school training,” wrote a reviewer of a 1964 exhibition. “He is already showing himself a sensitive handler of oil paint who wisely limits his palette to gain richness and density.” (Barrett had displayed a prodigious early talent for achieving these qualities in watercolor — see, for example, an impressive, impressionistic still-life of orange dahlias, auctioned off in 2021, made when the artist was only 15.)

His training gave him the confidence to break away from formal exercises during this period and experiment with different styles and subjects, from the disturbing, primitivist Lions to the hollow-eyed, Munch-like Portrait of a Girl. Barrett’s first student period ended in the mid-sixties, as Pink Floyd began to take off and Barrett “turned into a songwriter” (then-manager Andrew King later wrote) “it seemed like overnight.”

After his spell with Pink Floyd and brief solo recording career came to an end, Barrett moved back to Cambridge with his mother in 1978, dropped the nickname “Syd” and began painting again as Roger Barrett, avoiding any mention of life in music. From that year until he died, he worked in several styles and different media, painting striking abstractions and landscapes and even making his own furniture designs.

While he burned many canvases, many from this time survive. See a selected chronology of his work in the video above and in the photos here. Try to put aside the story of Syd Barrett the tragic Pink Floyd frontman, and let the work of Roger Barrett the artist inspire you.

Related Content:

Syd Barrett’s “Effervescing Elephant” Comes to Life in a New Retro-Style Animation

Understanding Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here, Their Tribute to Departed Bandmate Syd Barrett

Watch David Gilmour Play the Songs of Syd Barrett, with the Help of David Bowie & Richard Wright

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.