Christmas cards aren’t just an anachronism.

They’re almost an endangered species, the victim of the Internet, postal rate increases, and the jettisoning of any time consuming tradition whose execution has been found to bring the opposite of joy.

Above, Victoria and Albert Museum curators Alice Power and Sarah Beattie take us on a backwards trip to a time when the exchange of Christmas cards was a source of true social merriment.

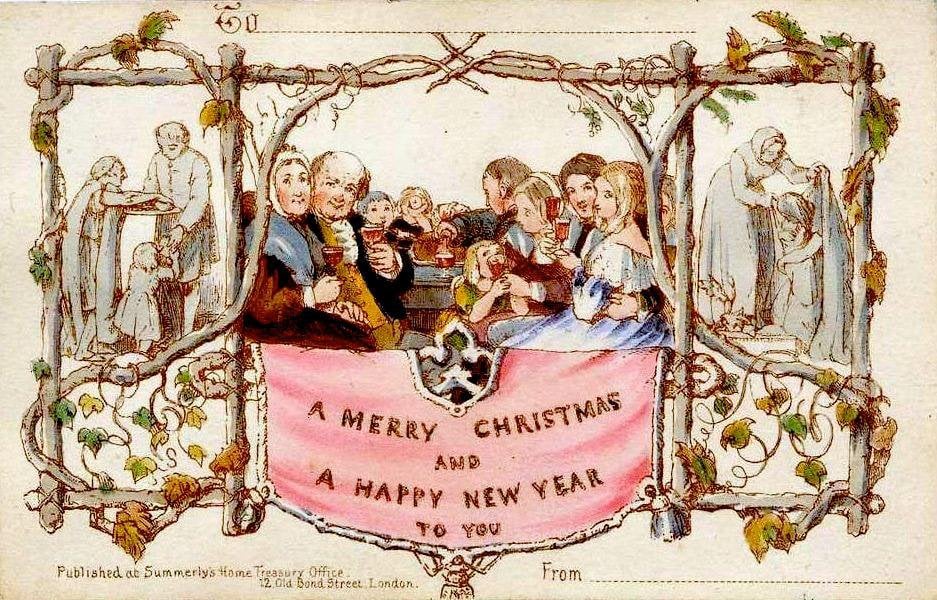

Christmas cards must hold a special place in both the V&A’s collections and heart, given that the museum’s founder, Henry Cole, inadvertently invented them in 1843.

As a well respected man about town, he received a great many more holiday letters than he had time or inclination to respond to, but neither did he wish to appear rude.

So he enlisted his friend, painter J.C. Horsley, to create a festive illustration with a built-in holiday greeting, leaving just enough space to personalize with a recipient’s name and perhaps, a handwritten line or two.

He then had enough postcard-sized reproductions printed up to send to 1000 of his friends.

(It’s hell being popular…)

Talk about zeitgeist: Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol was first published that very same holiday season.

No wonder everyone wanted in on the fun.

Part of the reason the cards in the V&A’s collection are so well preserved is that their recipients prized them enough to keep them in souvenir albums.

Understandably. They’re very appealing little artifacts.

The upper crust could afford such fancy design elements as clever die-cut shapes, pop up elements, and translucent windows that encouraged the recipients to hold them up to actual windows.

Technological advances in the printing industry, and the creation of the cost-effective Penny Post allowed those whose budgets were more modest than Mr. Cole’s to participate too.

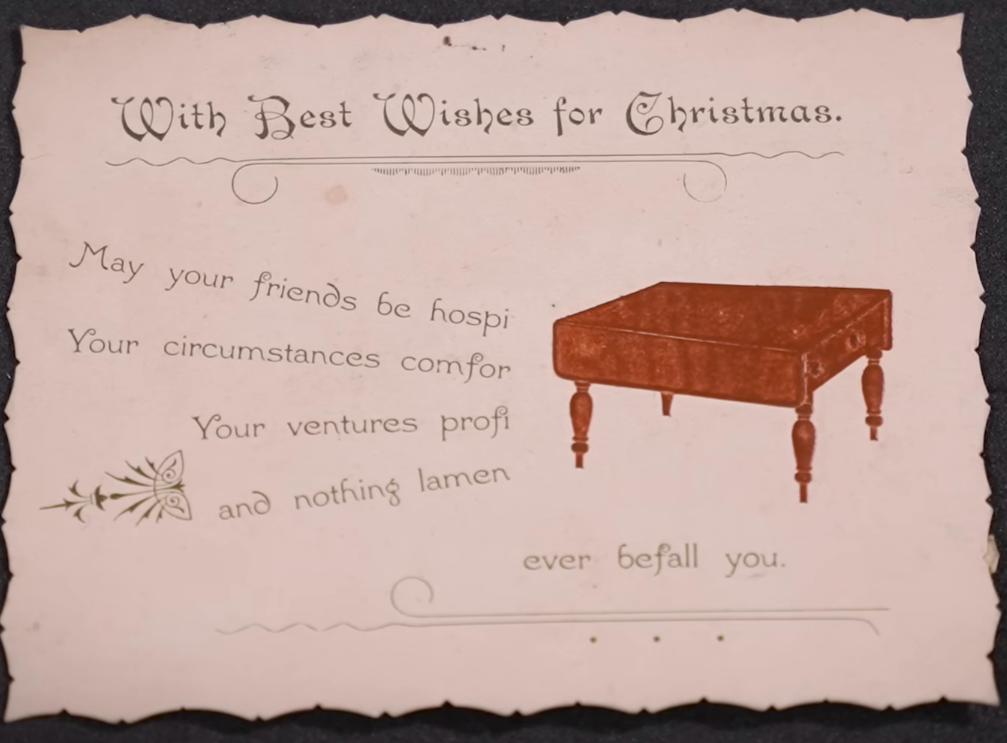

Their cards tended to be simpler in execution, though not necessarily concept.

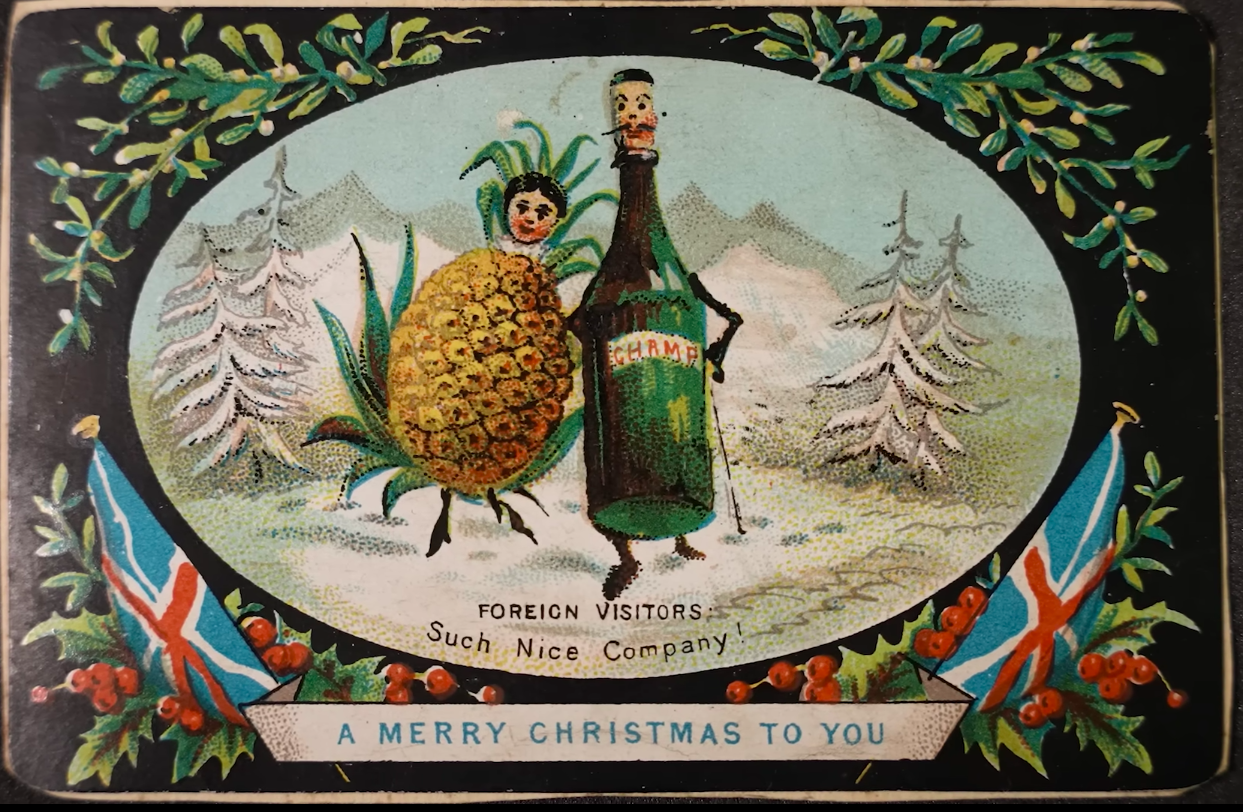

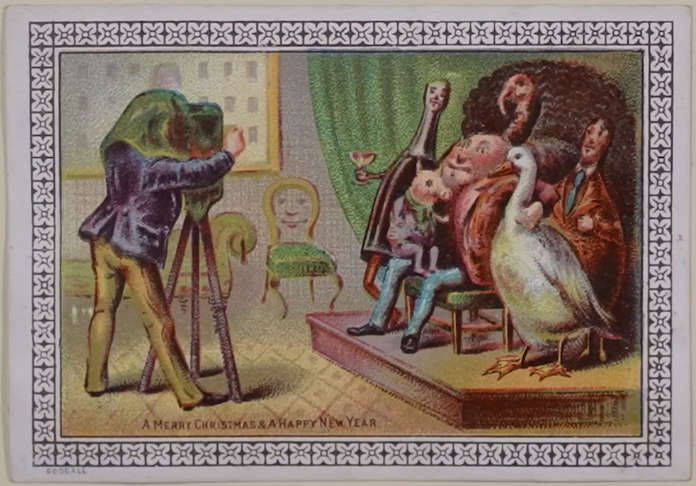

In addition to the views we’ve come to expect — winter, Father Christmas, holly — the Victorians had a thing for jolly anthropomorphized food and some truly shameless puns.

Enjoy these Ghosts of Christmas Past, dear readers. We’re almost inspired to revive the tradition!

Read more about the advent of this tradition, including how it jumped the pond, in Smithsonian Magazine’s History of the Christmas Card.

Related Content

When Salvador Dalí Created Christmas Cards That Were Too Avant Garde for Hallmark (1960)

J.R.R. Tolkien Sent Illustrated Letters from Father Christmas to His Kids Every Year (1920–1943)

Langston Hughes’ Homemade Christmas Cards From 1950

Watch Terry Gilliam’s Animated Short, The Christmas Card (1968)

Hear Neil Gaiman Read A Christmas Carol Just Like Charles Dickens Read It

An Oscar-Winning Animation of Charles Dickens’ Classic Tale, A Christmas Carol (1971)

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.