As a child, Jeff De Boer, the son of a sheet metal fabricator, was fascinated by the European plate armor collection in Calgary’s Glenbow Museum:

There was something magical or mystical about that empty form, that contained something. So what would it contain? A hero? Do we all contain that in ourselves?

After graduating from high school wearing a partial suit of armor he constructed for the occasion, De Boer completed seven full suits, while majoring in jewelry design at the Alberta College of Art and Design.

A sculpture class assignment provided him with an excuse to make a suit of armor for a cat. The artist had found his niche.

Using steel, silver, brass, bronze, nickel, copper, leather, fiber, wood, and his delicate jewelry making tools, DeBoer became the cats’ armorer, spending anywhere from 50 to 200 hours producing each increasingly intricate suit of feline armor. A noble pursuit, but one that inadvertently created an “imbalance in the universe”:

The only way to fix it was to do the same for the mouse.

“The suit of armor is a transformation vehicle. It’s something that only the hero would wear,” De Boer notes.

Fans of David Petersen’s Mouse Guard series will need no convincing, though no real mouse has had the misfortune to find its way inside one of his astonishing, custom-made creations.

Not even a taxidermy specimen, he revealed on the Making, Our Way podcast:

It’s not an altogether bad idea. The only reason I don’t do it is that hollow suit of armor like you might see in a museum, your imagination will make it do a million things more than if you stick a mouse in it will ever do. I have put armor on cats. I can tell you, it’s nothing like what you think it’s going to be. It’s not a very good experience for the cat. It does not fulfill any fantasies about a cat wearing a suit of armor.

Though cats were his entry point, De Boer’s sympathies seem aligned with the underdog — er, mice. Equipping humble, hypothetical creatures with exquisitely wrought, historical protective gear is a way of pushing back against being perceived differently than one wishes to be.

Accepting an Honorary MFA from his alma mater earlier this year, he described an armored mouse as a metaphor for his “ongoing cat and mouse relationship with the world of fine art…a mischievous, rebellious being who dares to compete on his own terms in a world ruled by the cool cats.”

Each tiny piece is preceded by painstaking research and many reference drawings, and may incorporate special materials like the Japanese silk haori-himo cord lacing the shoulder plates to the body armor of a Samurai mouse family.

Additional creations have referenced Mongolian, gladiator, crusader, and Saracen styles — this last perfect for a Persian cat.

“I mean, “Why not?” he asks in his TED‑x Talk,Village Idiots & Innovation, below.

His latest work combines elements of Maratha and Hussar armor in a veritable puzzle of minuscule pieces.

See more of Jeff De Boer’s cat and mouse armor on his Instagram.

Related Content

What’s It Like to Fight in 15th Century Armor?: A Surprising Demonstration

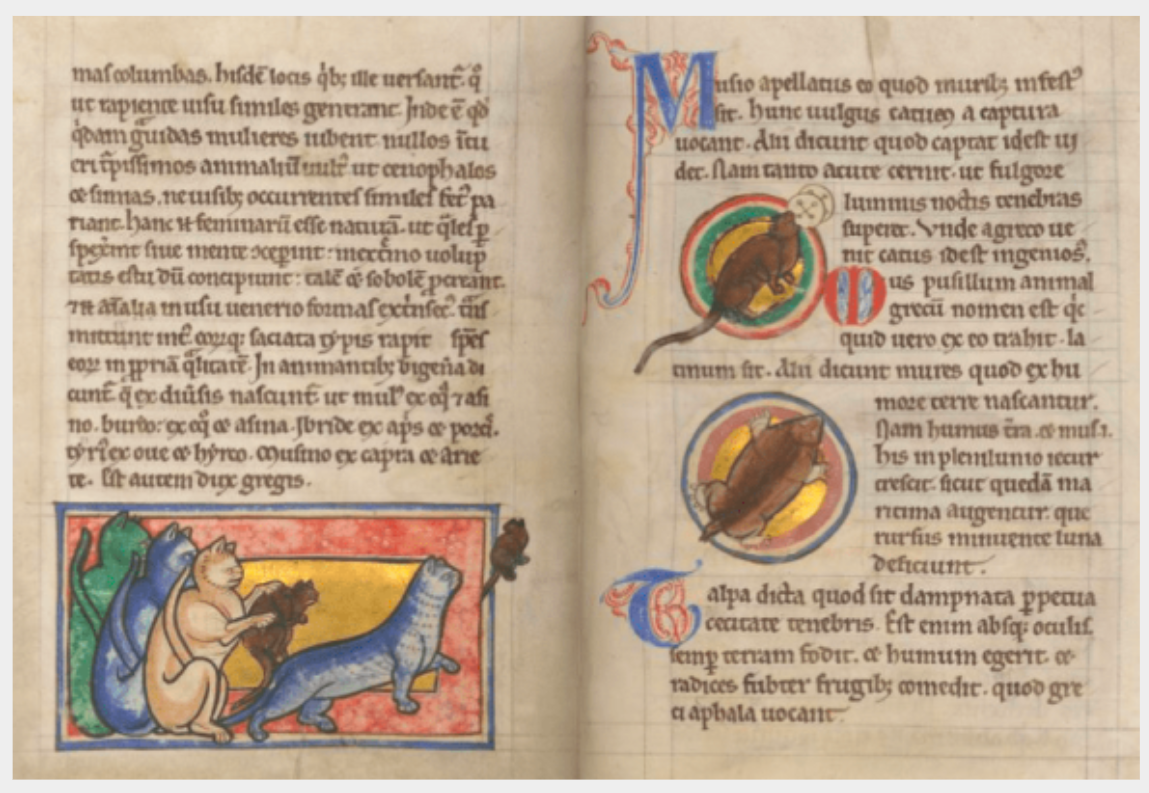

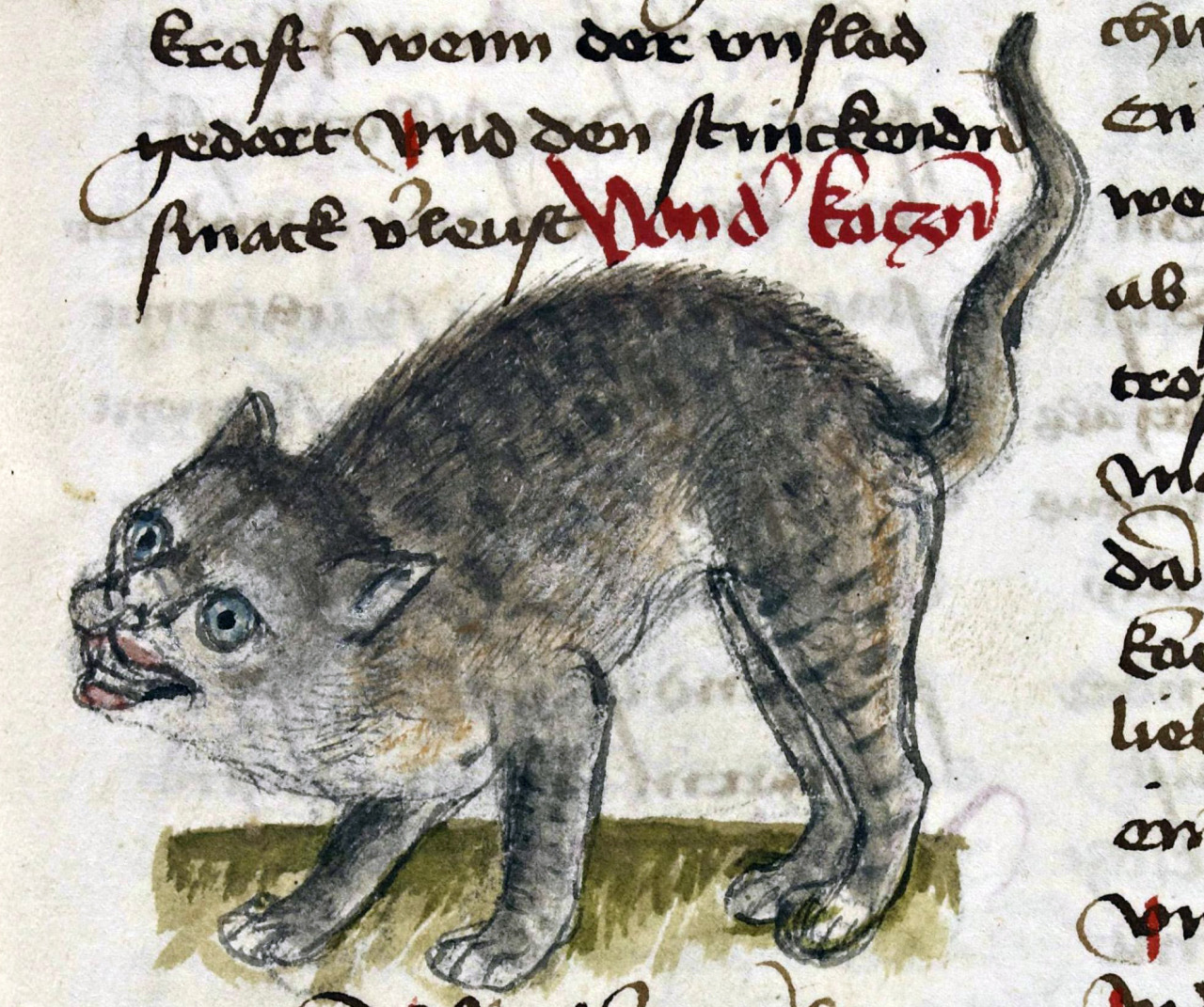

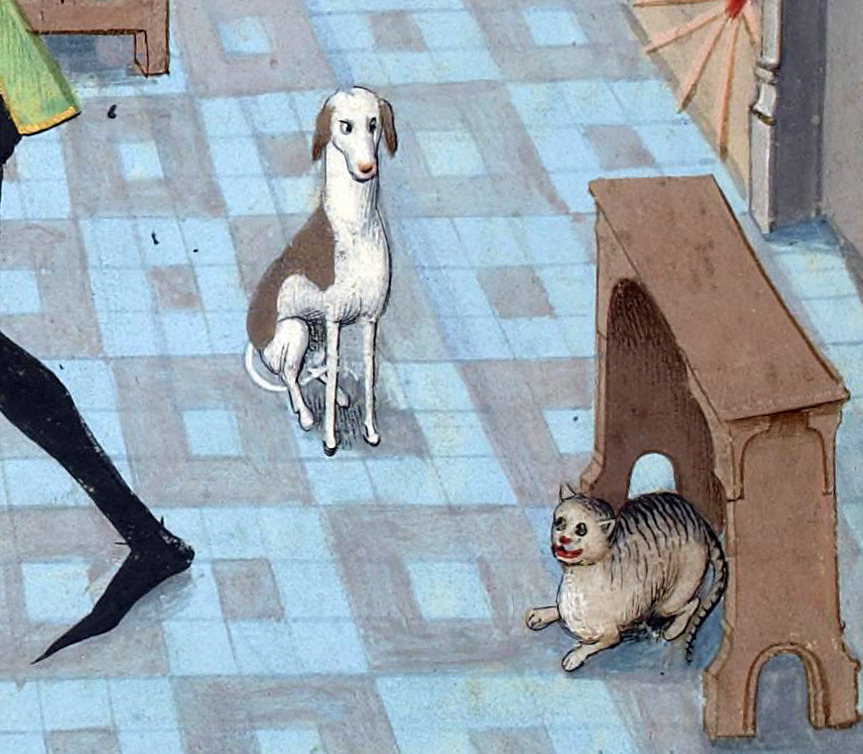

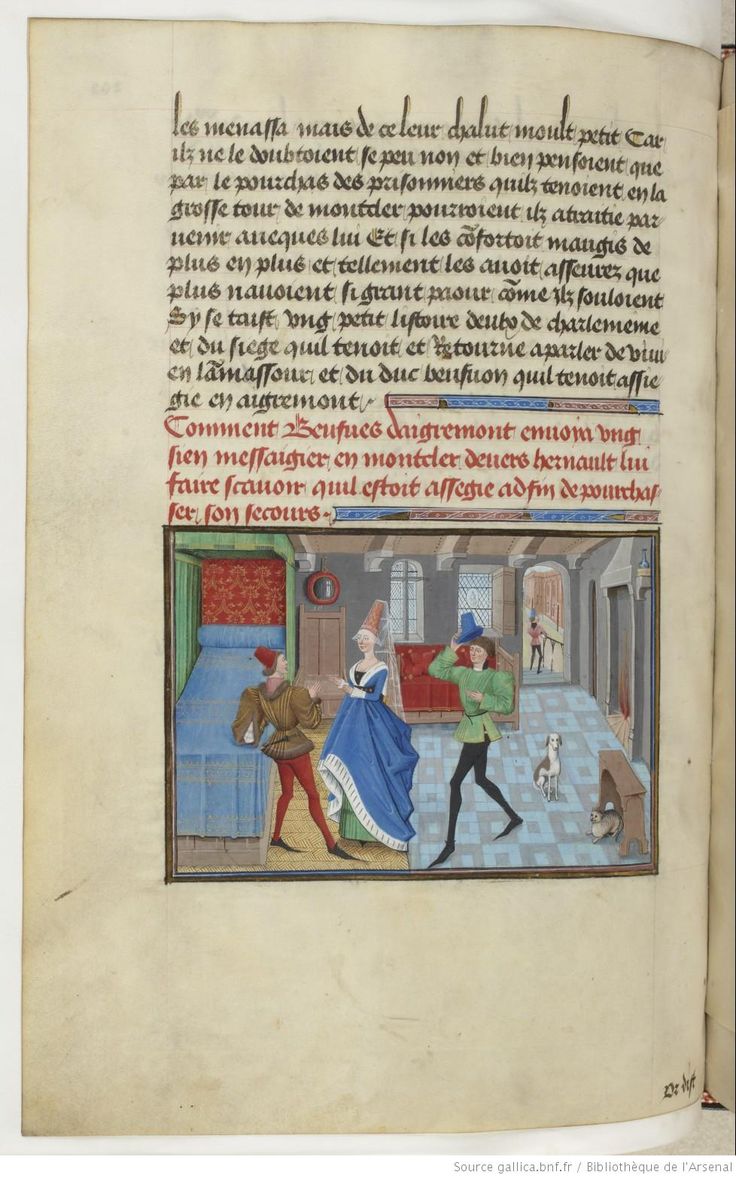

Cats in Medieval Manuscripts & Paintings

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.