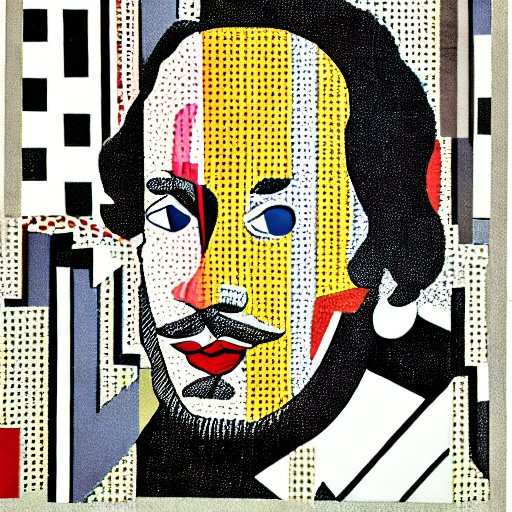

William Shakespeare’s plays have endured not just because of their inherent dramatic and linguistic qualities, but also because each era has found its own way of envisioning and re-envisioning them. The technology involved in stage productions has changed over the past four centuries, of course, but so has the technology involved in art itself. A few years ago, we featured here on Open Culture an archive of 3,000 illustrations of Shakespeare’s complete works going back to the mid-nineteenth century. That site was the PhD project of Cardiff University’s Michael Goodman, who has recently completed another digital Shakespeare project, this time using artificial intelligence: Paint the Picture to the Word.

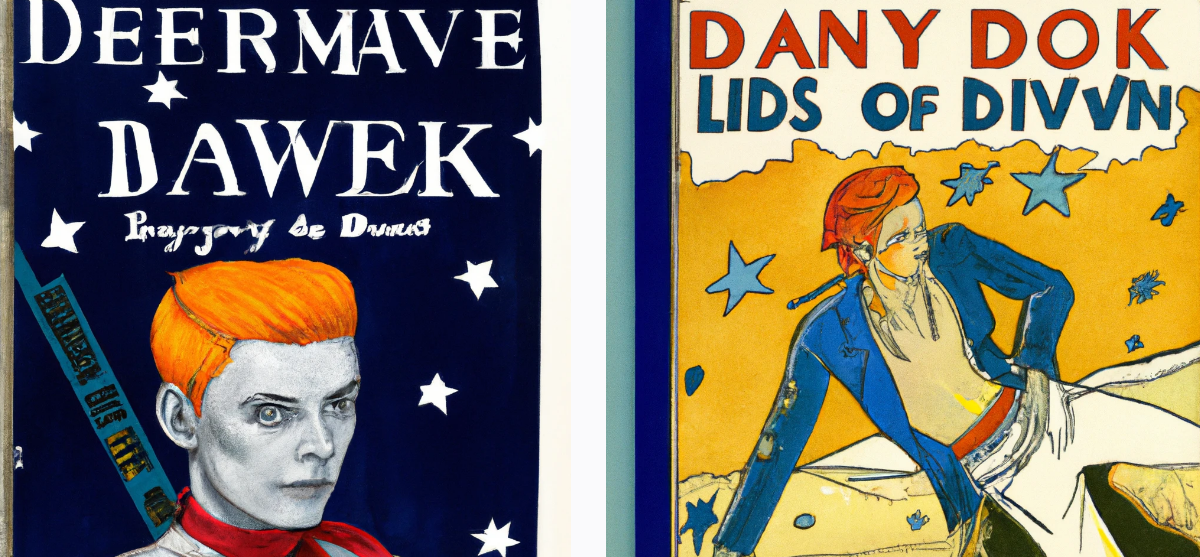

“Every image collected here has been generated by Stable Diffusion, a powerful text-to-image AI,” writes Goodman on this new project’s About page. “To create an image using this technology a user simply types a description of what they want to see into a text box and the AI will then produce several images corresponding to that initial textual prompt,” much as with the also-new AI-based art generator DALL‑E.

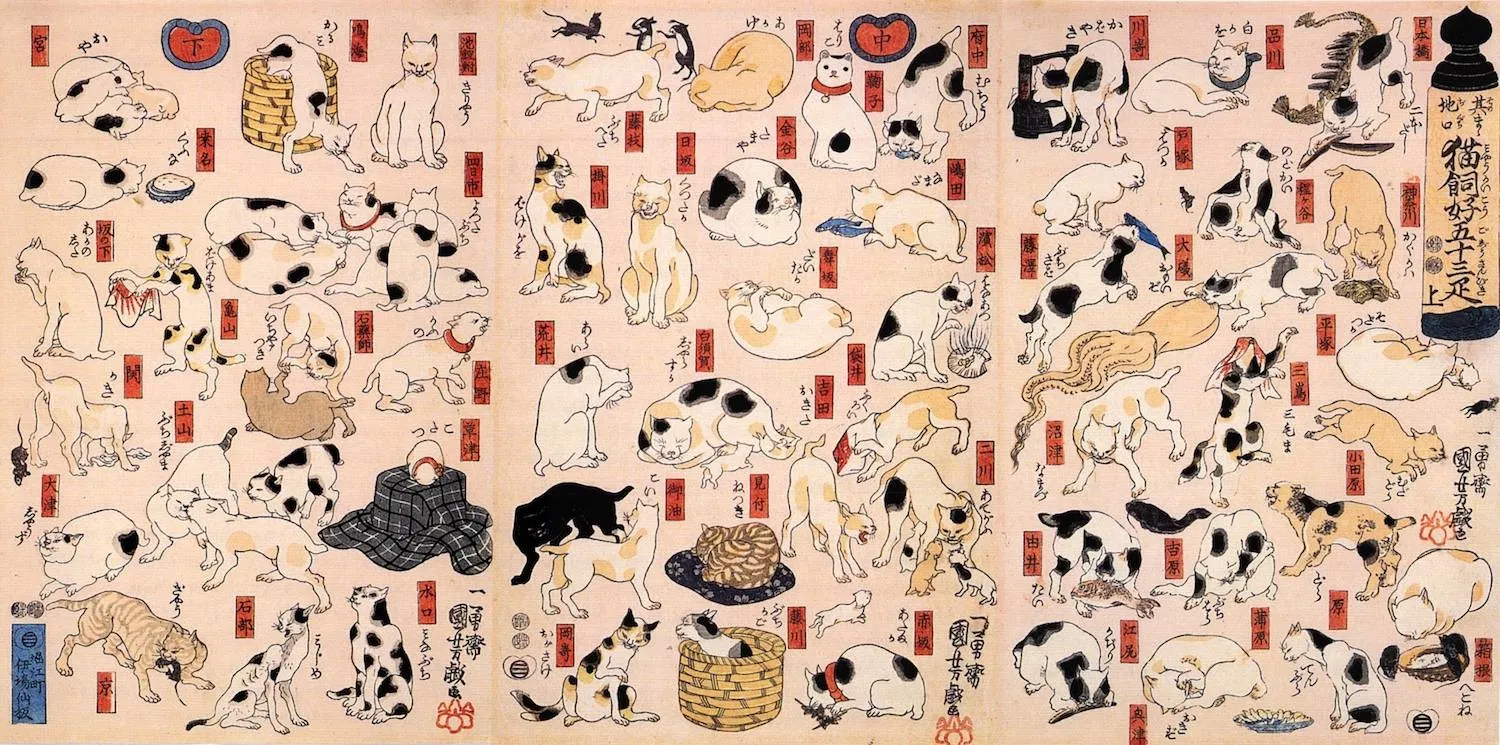

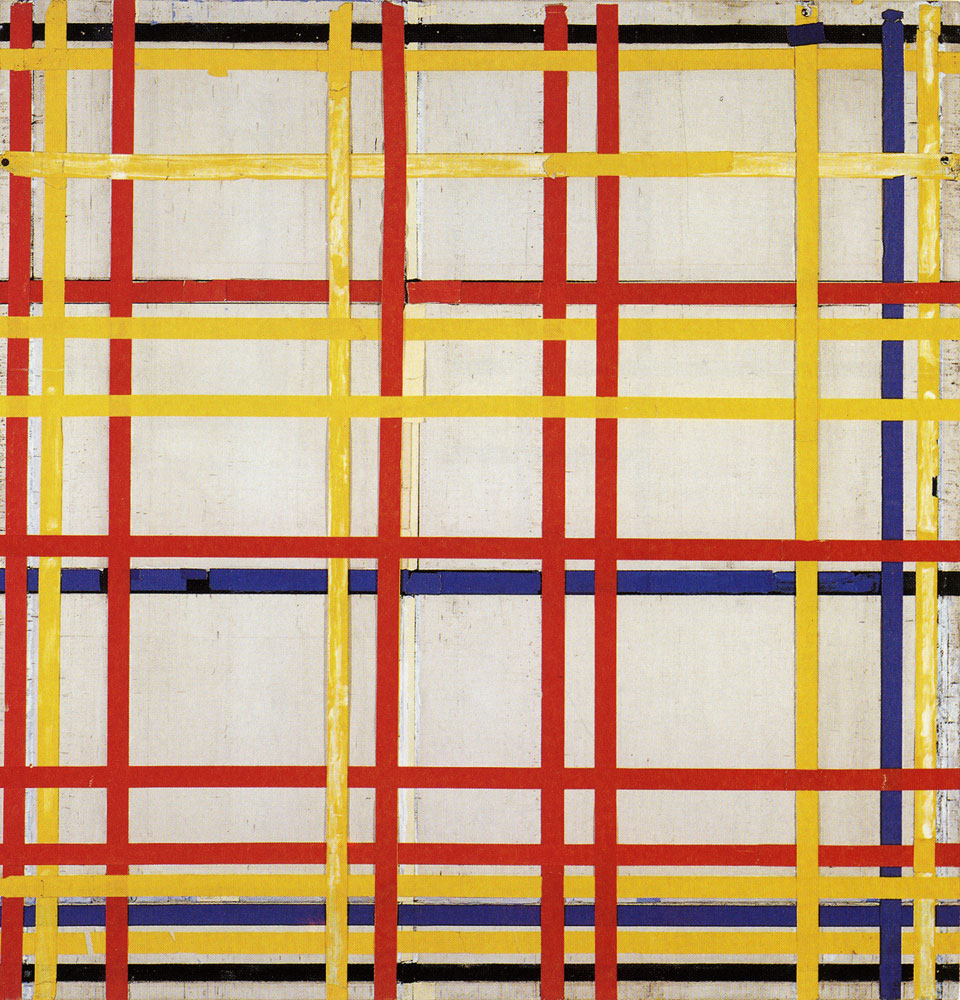

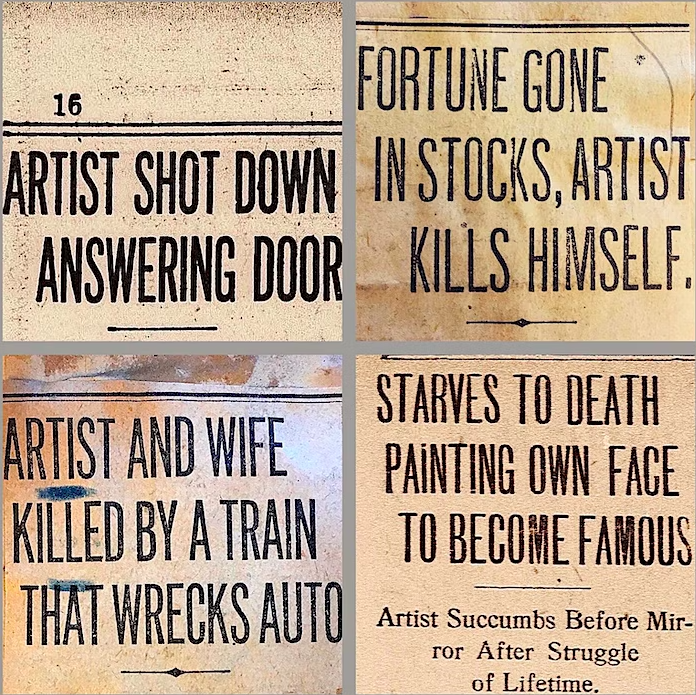

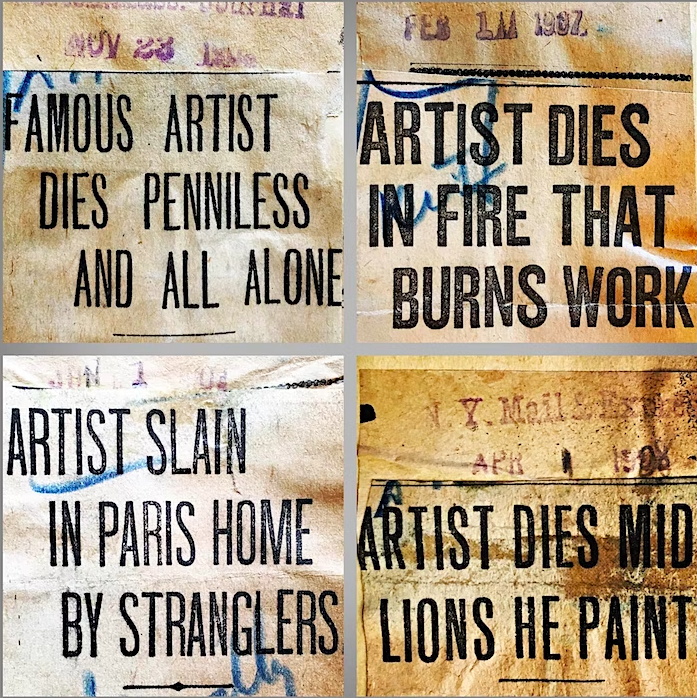

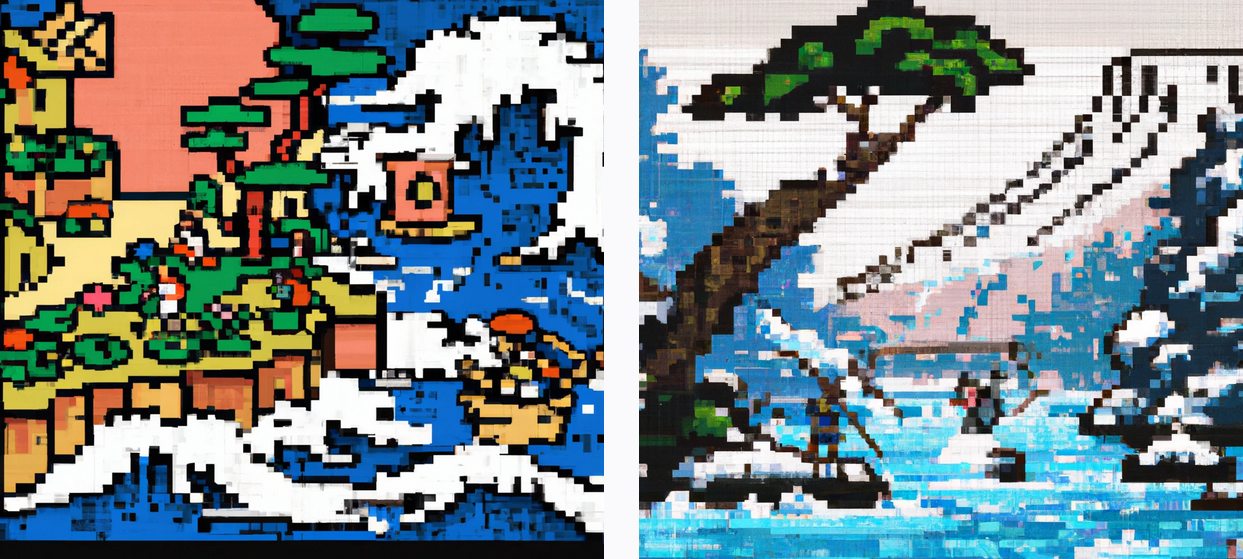

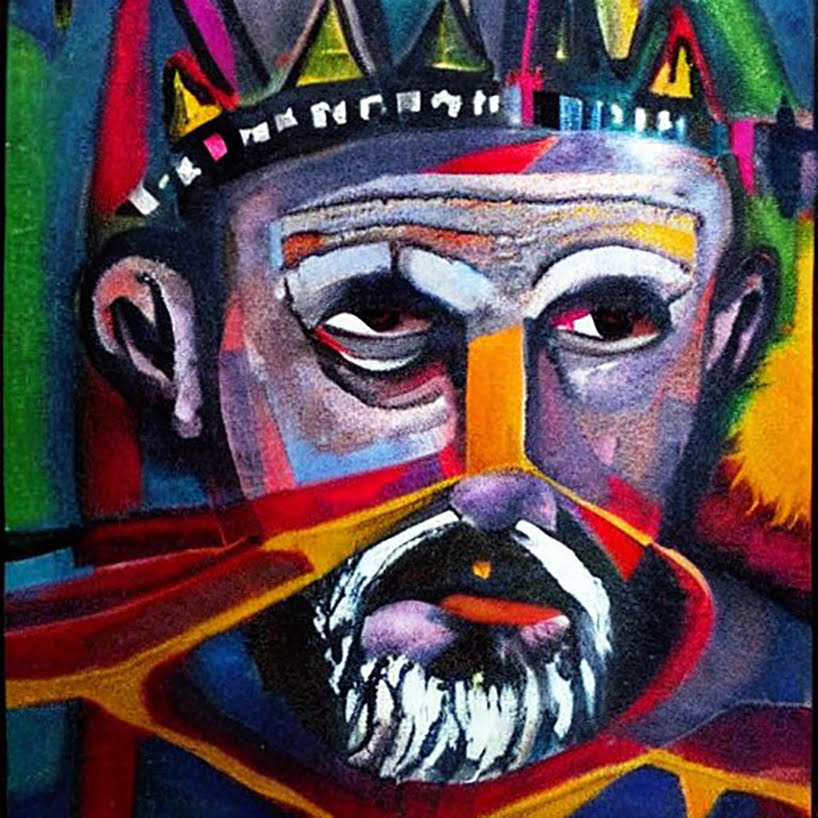

Each of the many images Goodman created is inspired by a Shakespeare play. “Some of the illustrations are expressionistic (King John, Julius Caesar), while some are more literal (Merry Wives of Windsor).” All “offer a visual idea or a gloss on the plays: Henry VIII, with the central characters represented in fuzzy felt, is grimly ironic, while in Pericles both Mariana and her father are seen through a watery prism, echoing that play’s concern with sea imagery.”

Selecting one of his many generated images per play, Goodman has created an entire digital exhibition whose works never repeat a style or a sensibility, whether with a dog-centric nineteen-eighties collage representing Two Gentlemen of Verona, a starkly near-abstract vision of Macbeth’s Weird Sisters or Much Ado About Nothing rendered as a modern-day rom-com. Theater companies could hardly fail to take notice of these images’ potential as promotional posters, but Paint the Picture to the Word also demonstrates something larger: Shakespeare’s plays have long stimulated human intelligence, but they turn out to work on artificial intelligence as well. Visit Paint the Picture to the Word here.

Related content:

DALL‑E, the New AI Art Generator, Is Now Open for Everyone to Use

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.