Pierre-Joseph Redouté made his name by painting flowers, an achievement impossible without a meticulousness that exceeds all bounds of normality. He published his three-volume collection Les Roses and his eight-volume collection Les Liliacées between 1802 and 1824, and a glance at their pages today vividly suggests the painstaking nature of both his process for not just rendering those flowers, but also for seeing them properly in the first place. While Redouté’s works have long been available free online, the digital forms in which they’ve been available haven’t quite done them justice — certainly not to the mind of designer and data artist Nicholas Rougeux.

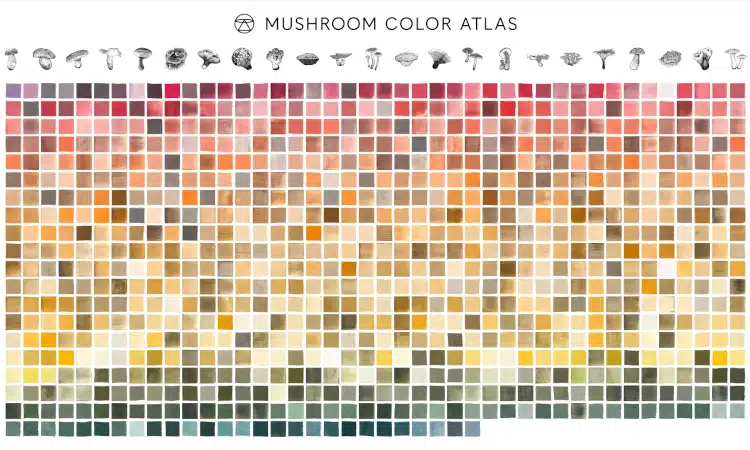

We’ve previously featured Rougeux here on Open Culture for his online restorations of a host of venerable artistic publications that lavishly capture the natural world: Illustrations of the Natural Orders of Plants; British & Exotic Mineralogy; A Monograph of the Trochilidæ, or Family of Humming-Birds; Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours; and Euclid’s Elements. Even having deep experience with those works, Rougeux can declare that, “simply put, Redouté’s illustrations are stunning. His attention to detail in stippling and watercolor has earned him the title ‘the Raphael of Flowers’ and is considered the greatest botanical illustrator of all time.”

Hence Rougeux’s decision to undertake a restoration of Les Roses and Les Liliacées, an “opportunity to become intimately familiar with his techniques and develop a deeper appreciation for his efforts.” The project ended up demanding eleven months, only some of which were taken up by bringing the original colors back to Redouté’s paintings, which “not only depict the physical characteristics of the roses but also convey their delicate beauty and fragrance.” Rougeux also had to digitally re-create the reading experience of these books for the internet, custom-designing a digital gallery for viewing their roses and lilies as they pop out against their newly added dark backgrounds.

Placing all of Redouté’s flowers against those backgrounds entailed the real Photoshop labor, taking each image and “making the layer mask manually by carefully and slowly tracing along every edge” — for all 655 plates of Les Roses and Les Liliacées, as Rougeux writes in a detailed making-of blog post. “No matter the complexity, I traced every flower, every leaf, every stem, every root, and every hair to preserve all the details and ensure that Redouté’s hard work looked as good on a dark background as it did on a light one.” Translating art from one medium to another can be a supremely effective way to cultivate a full appreciation of the artist’s skill — and in this case, a no less full appreciation of his patience. See the online restoration of Les Roses et Les Liliacées here.

Related content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.