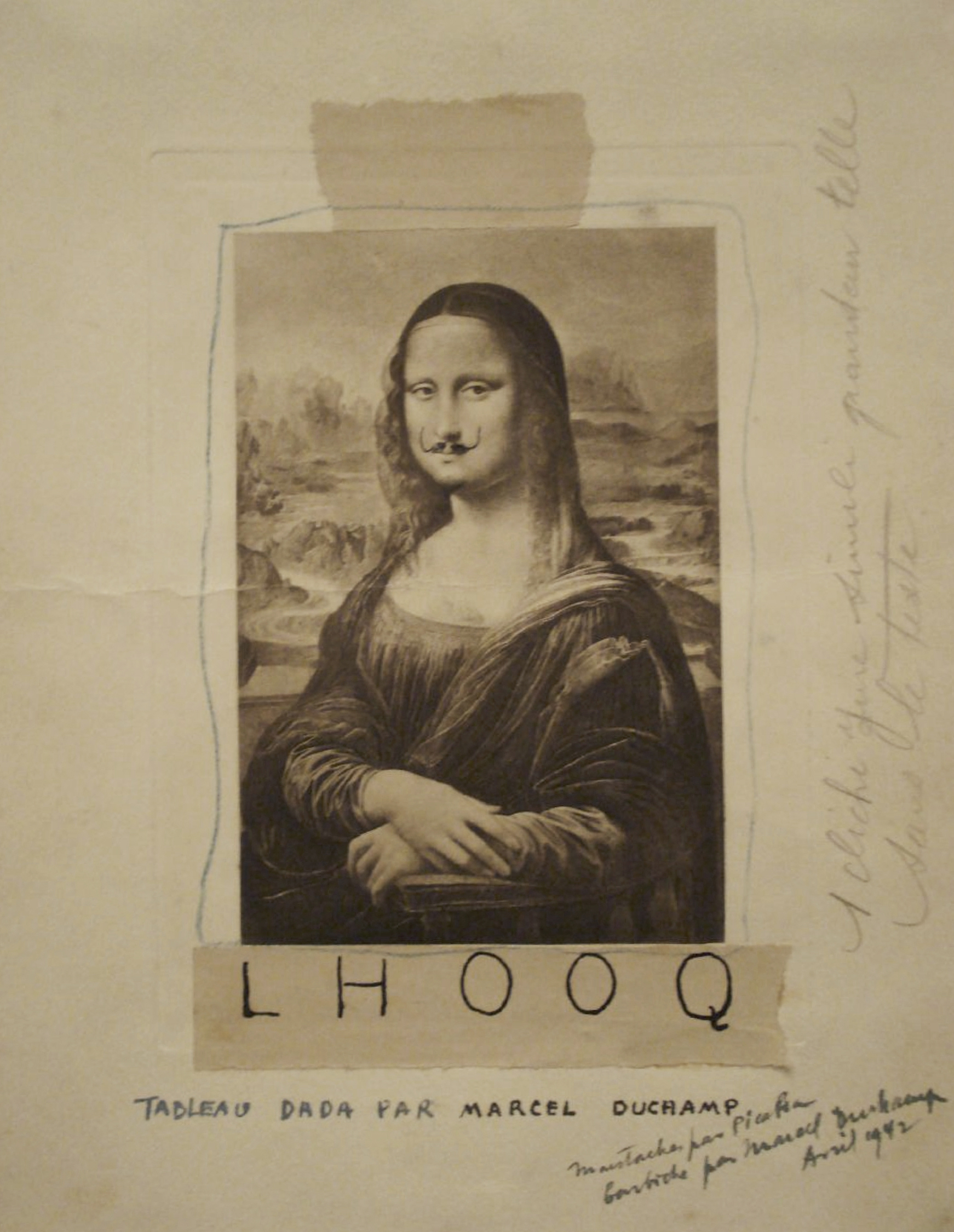

Apart from certain stretches of absence, Leonardo’s Mona Lisa has been on display at the Louvre for 228 years and counting. Though created by an Italian in Italy, the painting has long since been a part of French culture. At some point, the reverence for La Joconde, as the Mona Lisa is locally known, reached such an intensity as to inspire the label Jocondisme. For Marcel Duchamp, it all seems to have been a bit much. In 1919, he bought a postcard bearing the image of that most famous of all paintings, drew a mustache and goatee on it, and dubbed the resulting “artwork” L.H.O.O.Q., whose French pronunciation “Elle a chaud au cul” translates to — as Duchamp modestly put it — “There is fire down below.”

A century ago, this was a highly irreverent, even blasphemous act, but also just what one might expect from the man who, a couple years earlier, signed a urinal and put it on display in a gallery. Like the much-scrutinized Fountain, L.H.O.O.Q. was one of Duchamp’s “readymades,” or artistic provocations executed by modifying and re-contextualizing found objects.

Neither was singular: just as Duchamp signed multiple urinals, he also drew (or didn’t draw) facial hair on multiple Mona Lisa postcards. In one instance, he even gave the okay to his fellow artist Francis Picabia to make one for publication in his magazine in New York as, nevertheless, “par Marcel Duchamp” — though it lacked a goatee, an omission the artist corrected in his own hand some twenty years later.

In the 1956 interview just above, Duchamp describes L.H.O.O.Q. as a part of his “Dada period” (and, with characteristic modesty, “a great iconoclastic gesture on my part”). He also brings out a fake check — belonging to “no bank at all” — that he created to use at the dentist (who accepted it); and a system designed to “break the bank at Monte Carlo” (which stubbornly remained unbroken). “I believe that art is the only form of activity in which man, as a man, shows himself to be a true individual, and is capable of going beyond the animal state,” he declares. With his collision of Jocondisme and Dada, among the other unlikely juxtapositions he engineered, he showed himself to be the premier prankster of early twentieth-century art — and one whose pranks transcended amusement to inspire a scholarly industry that persists even today.

Related content:

What Makes the Mona Lisa a Great Painting: A Deep Dive

How Did the Mona Lisa Become the World’s Most Famous Painting?: It’s Not What You Think

How Marcel Duchamp Signed a Urinal in 1917 & Redefined Art

When Brian Eno & Other Artists Peed in Marcel Duchamp’s Famous Urinal

Salvador Dalí Reveals the Secrets of His Trademark Moustache (1954)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.