No historical figure better fits the definition of “Renaissance man” than Leonardo da Vinci, but that term has become so overused as to become misleading. We use it to express mild surprise that one person could use both their left and right hemispheres equally well. But in Leonardo’s day, people did not think of themselves having two brains, and the worlds of art and science were not so far apart as they are now.

That Leonardo was able to combine fine arts and fine engineering may not have been overly surprising to his contemporaries, though he was an extraordinarily brilliant example of the phenomenon. The more we learn about him, the more we see how closely related the two pursuits were in his mind.

He approached everything he did as a technician. The uncanny effects he achieved in painting were the result, as in so much Renaissance art, of mathematical precision, careful study, and firsthand observation.

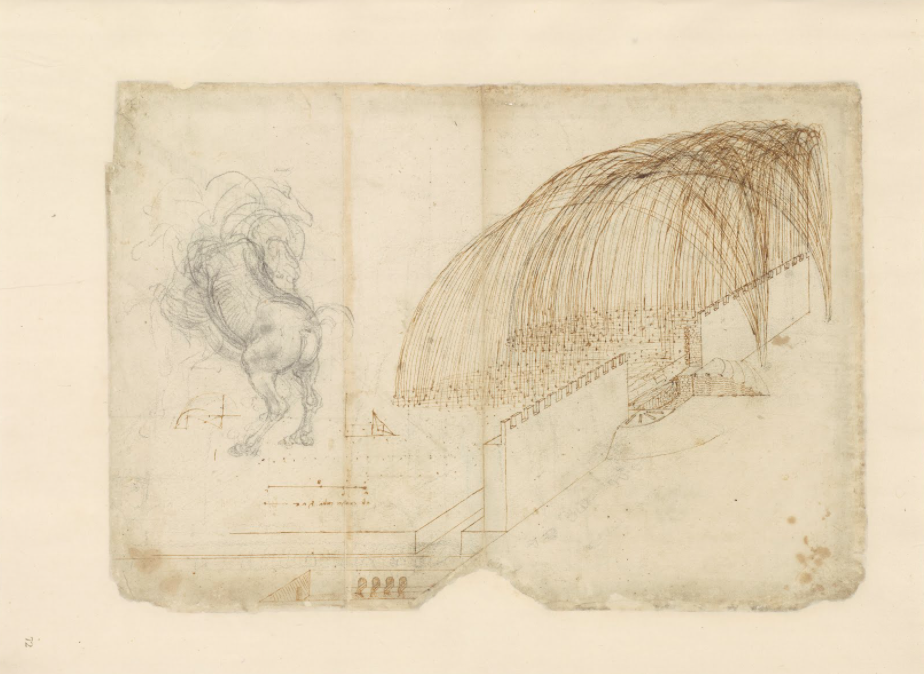

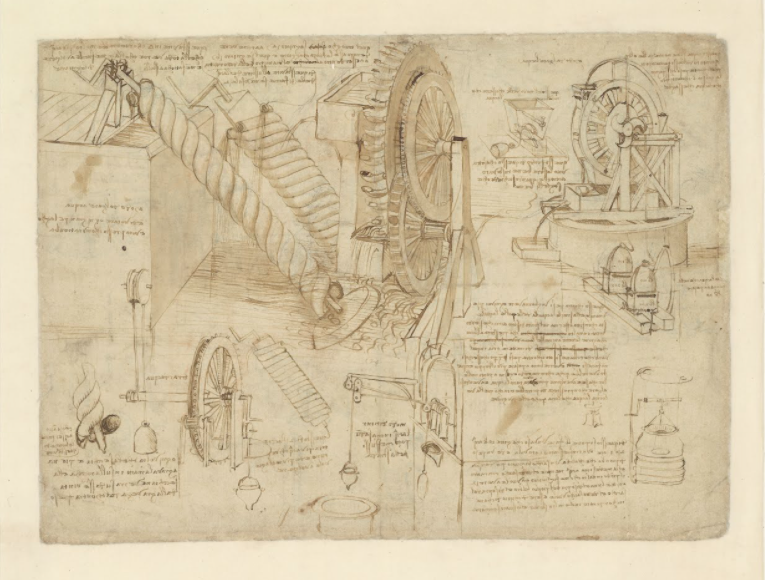

His artistic projects were also experiments. Some of them failed, as most experiments do, and some he abandoned, as he did so many scientific projects. No matter what, he never undertook anything, whether mechanical, anatomical, or artistic, without careful planning and design, as his copious notebooks testify. As more and more of those notebooks have become available online, both Renaissance scholars and laypeople alike have learned considerably more about how Leonardo’s mind worked.

First, there was the Codex Arundel, digitized by the British Library and made freely available. It is, writes Jonathan Jones at The Guardian, “the living record of a universal mind”—but also, specifically, the mind of a “technophile.” Then, the Victoria and Albert National Art Library announced the digitization of Codex Forster, which contains some of Leonardo’s earliest notebooks. Now The Visual Agency has released a complete digitization of Leonardo’s Codex Atlanticus, a huge collection of the artist, engineer, and inventor’s finely-illustrated notes.

(Note: If you speak English, make sure you click the “EN” button at the bottom right hand corner of the site. Also see “How to Read” at the top of the site.)

“No other collection counts more original papers written by Leonardo,” notes Google. The Codex Atlanticus “consists of 1119 papers, most of them drawn or written on both sides.” Its name has “nothing to do with the Atlantic Ocean, or with some esoteric, mysterious content hidden in its pages.” The 12-volume collection acquired its title because the drawings and writings were bound with the same sized paper that was used for making atlases. Gathered in the 16th century by sculptor Pompeo Leoni, the papers descended from Leonardo’s close student Giovan Francesco Melzi, who was entrusted with them after his teacher’s death.

The history of the Codex itself makes for a fascinating narrative, much of which you can learn at Google’s Ten Key Facts slideshow. The notebooks span Leonardo’s career, from 1478, when he was “still working in his native Tuscany, to 1519, when he died in France.” The collection was taken from Milan by Napoleon and brought to France, where it remained in the Louvre until 1815, when the Congress of Vienna ruled that all artworks stolen by the former Emperor be returned. (The emissary tasked with returning the Codex could not decipher Leonardo’s mirror writing and took it for Chinese.)

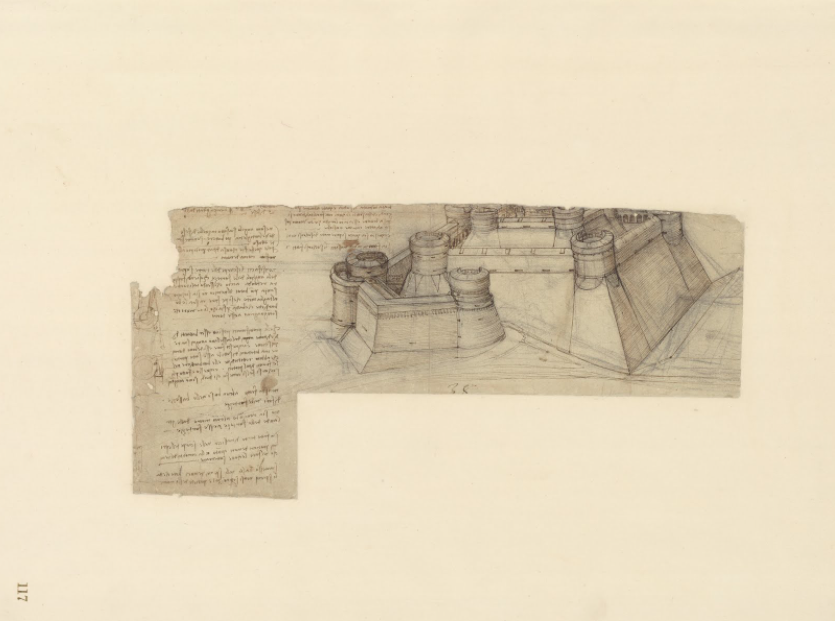

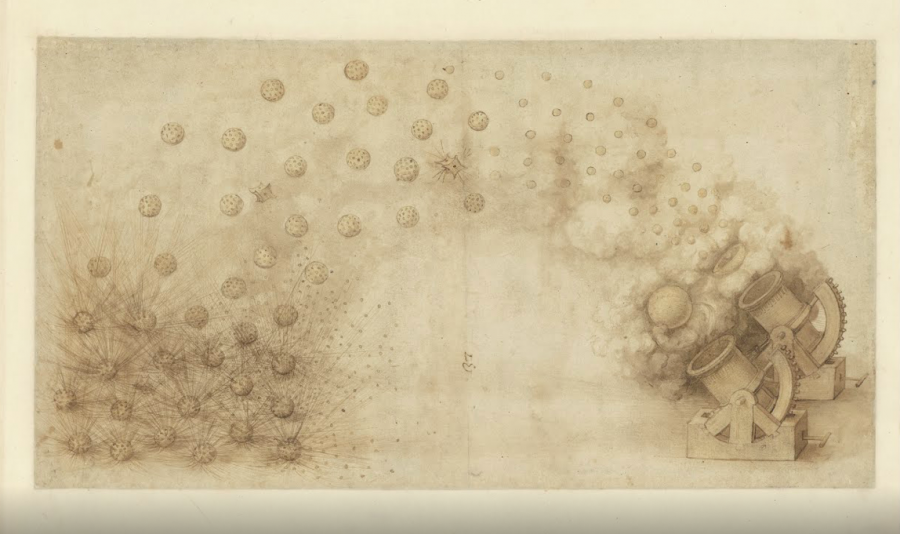

The Codex contains not only engineering diagrams, anatomy studies, and artistic sketches, but also fables written by Leonardo, inspired by Florentine literature. And it features Leonardo’s famed “CV,” a letter he wrote to the Duke of Milan describing in nine points his qualifications for the post of military engineer. In point four, he writes, “I still have very convenient bombing methods that are easy to transport; they launch stones and similar such in a tempest full of smoke to frighten the enemy, causing great damage and confusion.”

As if in illustration, elsewhere in the Codex, the drawing above appears, “one of the most celebrated” of the collection.” It was “shown to traveling foreigners visiting the Ambrosiana [the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, where the Codex resides] since the 18th century, usually arousing much amazement.” It is still amazing, especially if we consider the possibility that its artistry might have been something of a byproduct for its creator, whose primary motivation seems to have been solving technical problems—in the most elegant ways imaginable.

See the complete digitization of Leonardo’s Codex Atlanticus here. And again, click “EN” for English at the bottom of the site, and then “How to Read” at the top of the site.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

How Leonardo da Vinci Drew an Accurate Satellite Map of an Italian City (1502)

Leonardo da Vinci’s Handwritten Resume (1482)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness