There seems to be widespread agreement—something special was lost in the rushed-to-market move from physical media to digital streaming. We have come to admit that some older musical technologies cannot be improved upon. Musicians, producers, engineers spend thousands to replicate the sound of older analog recording technology, with all its quirky, inconsistent operation. And fans buy record players and vinyl records in surprisingly increasing numbers to hear the warm and fuzzy character of their sound.

Neil Young, who has relentlessly criticized every aspect of digital recording, has dismissed the resurgence of the LP as a “fashion statement” given that most new albums released on vinyl are digital masters. But buyers come to vinyl with a range of expectations, writes Ari Herstand at Digital Music News: “Vinyl is an entire experience. Wonderfully tactile…. When we stare at our screens for the majority of our days, it’s nice to look at art that doesn’t glow and isn’t the size of my hand.” Vinyl can feel and look as good as it sounds (when properly engineered).

While shiny, digitally mastered vinyl releases pop up in big box stores everywhere, the real musical wealth lies in the past—in thousands upon thousands of LPs, 45s, 78s—relics of “the only consumer playback format we have that’s fully analog and fully lossless,” says vinyl mastering engineer Adam Gonsalves. Few institutions can afford to store thousands of physical albums, and many rarities and oddities exist in vanishingly fewer copies. Their crackle and hiss may be forever lost without the intervention of digital preservationists like the Internet Archive.

The Archive is “now expanding its digitization project to include LPs,” reports Faye Lessler on the organization’s blog. This will come as welcome news to cultural historians, analog conservationists, and vinyl enthusiasts of all kinds, who will mostly agree that digitization is far better than extinction, though the tactile and visual pleasures may be irreplaceable. The Archive has focused its efforts on the over 100,000 audio recordings from the Boston Public Library’s collection, “in order to prevent them from disappearing forever when the vinyl is broken, warped, or lost.”

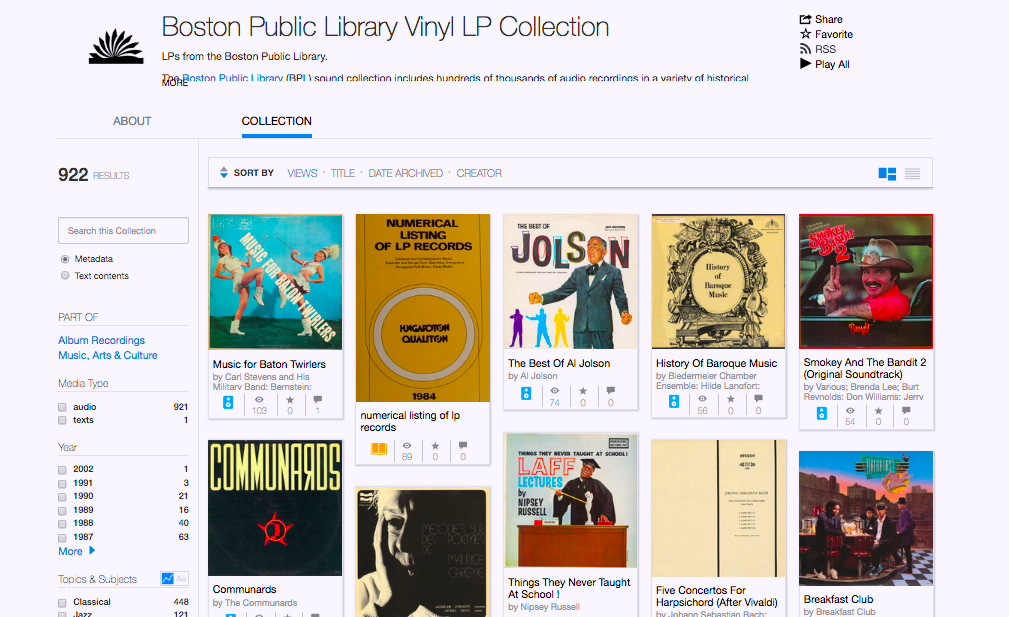

“These recordings exist in a variety of historical formats, including wax cylinders, 78 rpms, and LPs,” though the project is currently focused on the latter. “They span musical genres including classical, pop, rock, and jazz, and contain obscure recordings like this album of music for baton twirlers, and this record of radio’s all-time greatest bloopers.” The method of rapidly converting the artifacts at the rate of ten LPs per hour (which you can read more about at the Archive blog) serves as a testament to what digital technology does best—using machine learning and metadata to automate the archival process and create extensive, searchable databases of catalogue information.

Currently, the project has uploaded 1,180 recordings to its site, “but some of the albums are only available in 30 second snippets due to rights issues,” Lessler points out. Browse the “Unlocked Recordings” category to hear 750 digitized LPs available in full: these include a recording of Gian Carlo Menotti’s ballet The Unicorn, the Gorgon, and the Manticore, further up; The Begetting of the President, above, a satire of Nixon’s rise to power as Biblical epic, read by Orson Welles in his King of Kings’ voice; and Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto no. 1 in B‑flat minor, played by Van Cliburn, below.

The range and variety captured in this collection—from fireworks sound effects to Elton John’s second, self-titled album to classic Pearl Baily to 80s new wave band The Communards to Andres Segovia playing Bach to the Smokey and the Bandit 2 soundtrack—will outlast copyright restrictions. And they will leave behind an extensive record, no pun intended, of the LP: “our primary musical medium for over a generation,” says the Archive’s special projects director CR Saikley, “witness to the birth of both Rock & Roll and Punk Rock… integral to our culture from the 1950s to the 1980s.” Vinyl remains the most revered of musical formats for good reason—reasons future generations will discover, at least virtually, for themselves someday.

via Kottke

Related Content:

How Vinyl Records Are Made: A Primer from 1956

An Interactive Map of Every Record Shop in the World

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness