“Democracy is the worst form of government except all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” So said Winston Churchill, perhaps not suspecting how frequently the remark would be quoted in the decades thereafter. Time and experience continue to reveal to us democracy’s liabilities, but also — at least in certain societies — the nature of its surprising staying power. Since well before Churchill’s time, democracy and its workings have been objects of fascination the world over. So have its central questions, not least the one of just how to maintain the “informed citizenry” on which its operation supposedly depends.

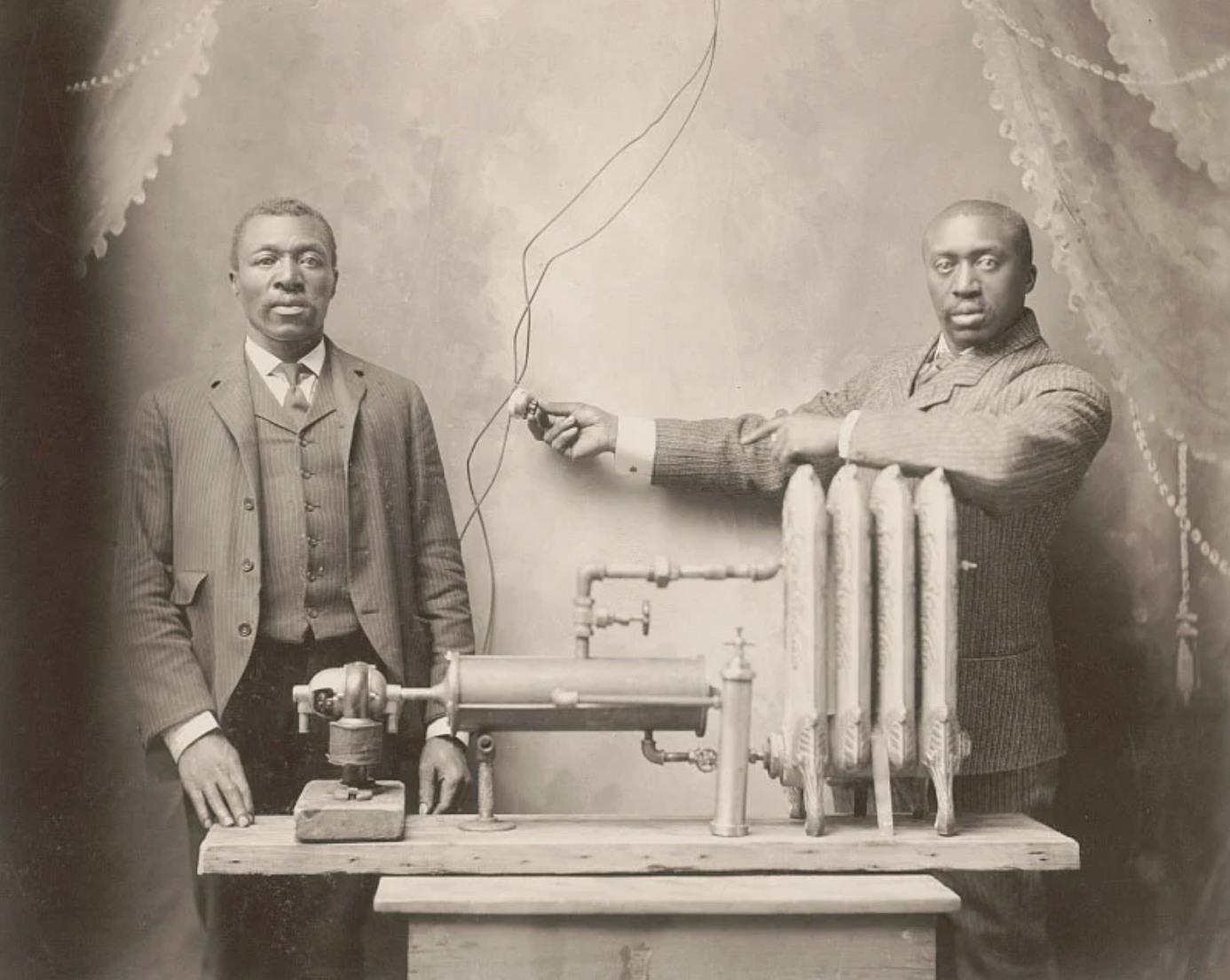

The Internet Archive has just launched its own kind of answer in the form of Democracy’s Library. “A free, open, online compendium of government research and publications from around the world,” the site offers citizens a way to “leverage useful research, learn about the workings of their government, hold officials accountable, and be more informed voters.”

Collected from a variety of governmental bodies like the United States’ National Agricultural Library, Foreign Broadcast Information Service, and National Institute of Standards and Technology Research Library — as well as Statistics Canada and Public Accounts of Canada — its materials were ostensibly produced for the public, but haven’t always been easy to find. It total, there are more than 500,000 documents in the collection.

“Governments have created an abundance of information and put it in the public domain, but it turns out the public can’t easily access it,” says Brewster Kahle, founder of the Internet Archive. He gives one of the series of talks that comprise “Building Democracy’s Library,” the launch celebration that took place last week and that you can still watch in the video above. Its proceedings go into quite a bit of detail about the efforts of acquisition and organization that went into this project, as well as the nature of its mission. For this isn’t just an effort to document democracy, but to strengthen it by making the information it produces available as conveniently as possible to as many citizens as possible. And no matter the country of which you count yourself a citizen, you can start browsing Democracy’s Library here.

Related content:

Does Democracy Demand the Tolerance of the Intolerant? Karl Popper’s Paradox

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.