To be a New Yorker is to be a gourmand—of food carts, local diners, supermarkets, outer borough mercados, whatever latest upscale restaurant surfaces in a given season.… It is to be as likely to have a menu in hand as a newspaper, er… smartphone…, and it is to notice the design of said menus. Well, some of us have done that. Often the added attention goes unrewarded, but then sometimes it does. Now you, dear reader, can experience well over one-hundred years of staring at menus, thanks to the New York Public Library’s enormous digitized collection. Fancy a time warp through dining halls abroad? You’ll not only find several hundred New York restaurants represented here, but hundreds more from all over the world. With a collection of 17,000 menus and counting, a person could easily get lost.

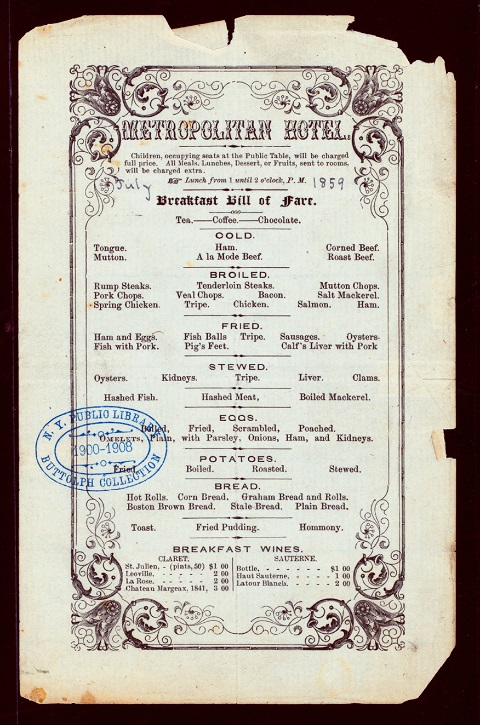

You may notice I used the word “gourmand,” and not “foodie” above. While it might be a gross anachronism to call someone a “foodie” in 1859, the year the menu for the Metropolitan Hotel (above) was printed, it might also import a cosmopolitan concept of dining that didn’t seem to exist, at least at this establishment. More than anything, the menu resembles the various descriptions of pub food that populate Joyce’s Ulysses. Though much of it was delicious, I’m sure, for heavy eaters of meat, eggs, potatoes, and bread, you won’t find a vegetable so much as mentioned in passing. The fare does include such hearty staples as “Hashed Fish,” “Stale Bread,” and “Breakfast Wine.” The design marries flowery Victorian elements with the kind of font found in Old West typesets.

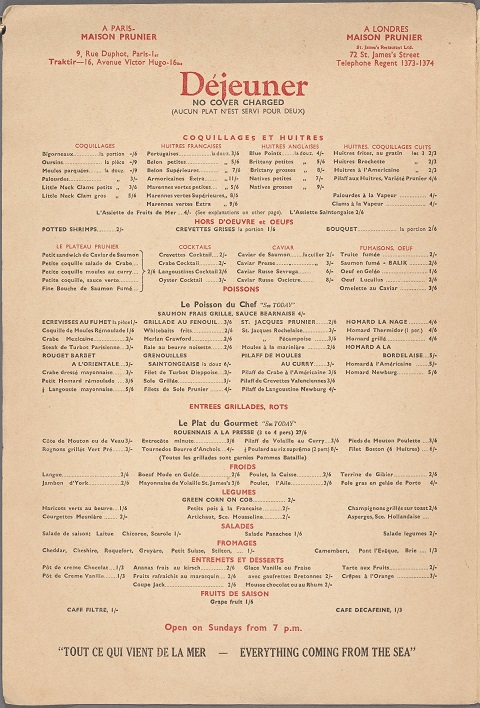

1939 was a good year for menus, at least in Europe. While New York institutions like the Waldorf Astoria practiced certain design austerities, the Maison Prunier, with locations in Paris and London, spared no expense in the printing of their full-color fishermans’ slice of life painting on the menu cover above and the elegant typography of its extensive contents below. A version was printed in English—though The New York Public Library (NYPL) doesn’t seem to have a copy of it digitized. One English phrase stands out at the bottom, however: the translation of “Tout Ce Qui Vient De La Mer–Everything From the Sea.” Other menus for this restaurant show the same kind of careful attention to design. Clicking on the pages of many of the NYPL menus—like this one from a 1938 Maison Prunier menu—brings up an interactive feature that links each dish to close-up views.

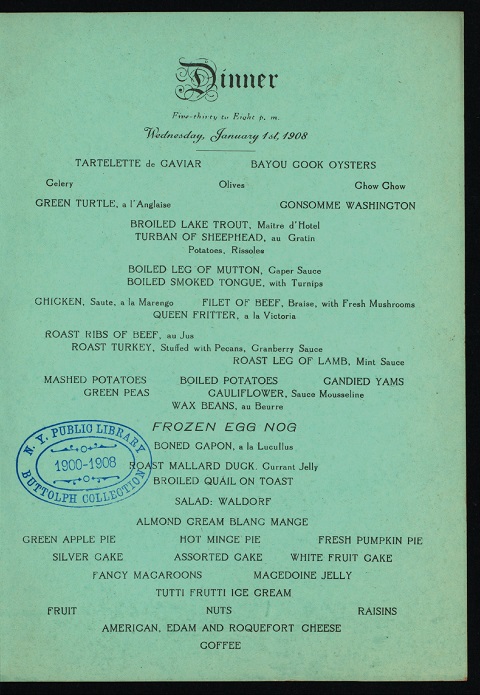

In a post on the NYPL menu collection, Buzzfeed specifically compares New York menus of today with those of 100 years ago, noting that prices quoted signify cents, not dollars. A 1914 Delmonico “Rib of Roast” would run you .75 cents, for example, while a 2014 rib eye there sells for 58 big ones. Of course then, as now, many restaurants considered it gauche to print prices at all. See, for example, the dinner menu at New Orleans’ St. Charles Hotel from 1908 below. We may have an all-inclusive feast here since this comes from a New Years Eve bill, which also includes a “Musical Program” in two parts and a list of local “Amusements” at such places as Blaney’s Lyric Theatre, Tulane, Dauphine, “French Orera” (sic), and the 2:00 pm races at City Park. Matinees and 8 o’clock shows every day except Sunday.

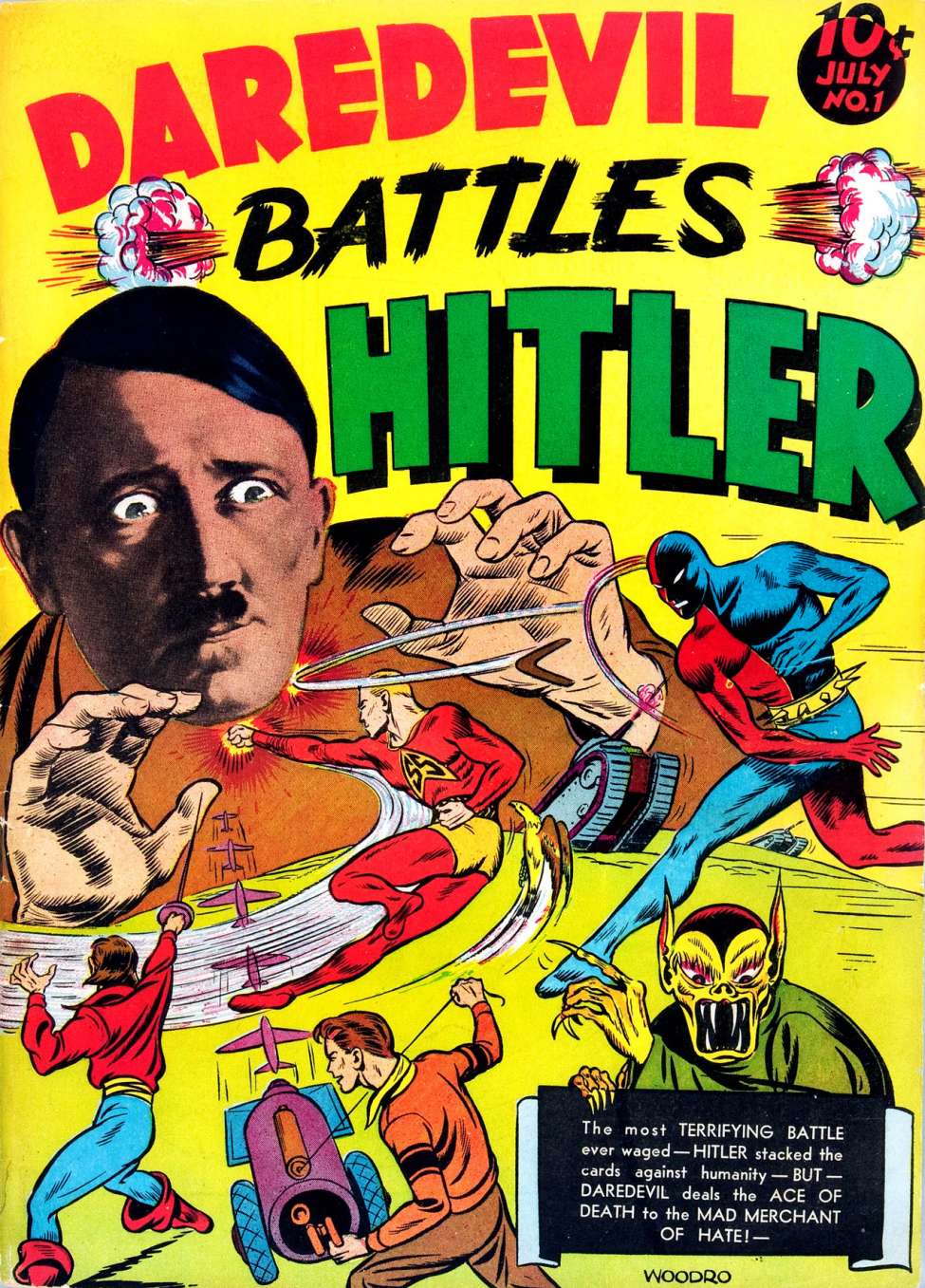

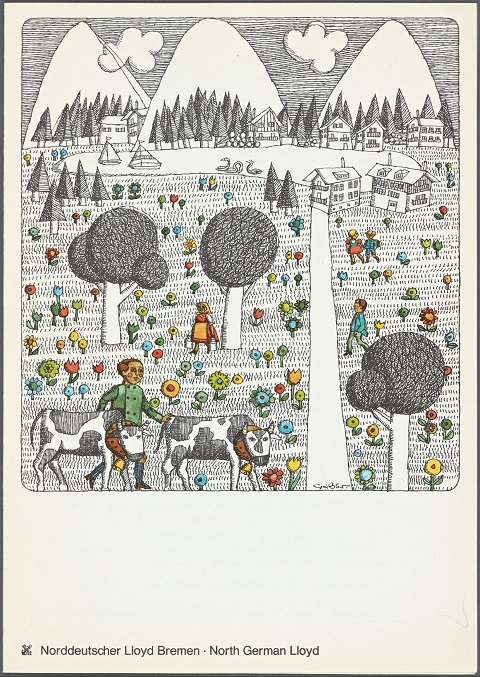

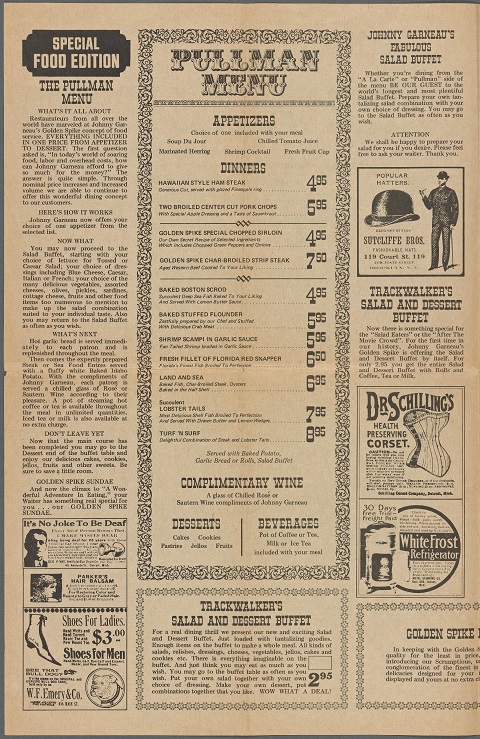

The sixties gave us an explosion of menus that parallel in many cases the breakout designs of magazine and album covers. See two standouts below. The North German Lloyd, just below, went with a funky children’s book-cover illustration for its 1969 menu cover, though its interior maintains a minimalist clarity. Below it, see the striking first page of a menu for Johnny Garneau’s Golden Spike from that same year. The cover boasts a nostalgic headline story for Promontory News: “Golden Spike is Driven: The last rail is laid! East meets West in Utah!” Put it on the cover of a Band or CSNY album and no one bats an eye.

See many, many, many more menus at the NYPL site. With the steady growth of food scholarship, this collection is certainly a boon to researchers, as well as curious gourmands, foodies, and rabid diners of all stripes.

via Buzzfeed

Related Content:

What Prisoners Ate at Alcatraz in 1946: A Vintage Prison Menu

Howard Johnson’s Presents a Children’s Menu Featuring Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Extensive Archive of Avant-Garde & Modernist Magazines (1890–1939) Now Available Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness