Online archives, galleries, and libraries offer Vegas-sized buffets for the senses (well two of them, anyway). All the art and photography your eyes can take in, all the music and spoken word recordings your ears can handle. But perhaps you’re still missing something? “Geordies banging spoons” maybe? Or “Tawang lamas blowing conch shell trumpets… Tongan tribesmen playing nose flutes…,” the sound of “the Assamese woodworm feasting on a window frame in the dead of night”?

No worries, the British Library’s got you covered and then some. In 2009, it “made its vast archive of world and traditional music available to everyone, free of charge, on the internet,” amounting to roughly 28,000 recordings and, The Guardian estimates “about 2,000 hours of singing, speaking, yelling, chanting, blowing, banging, tinkling and many other verbs associated with what is a uniquely rich sound archive.”

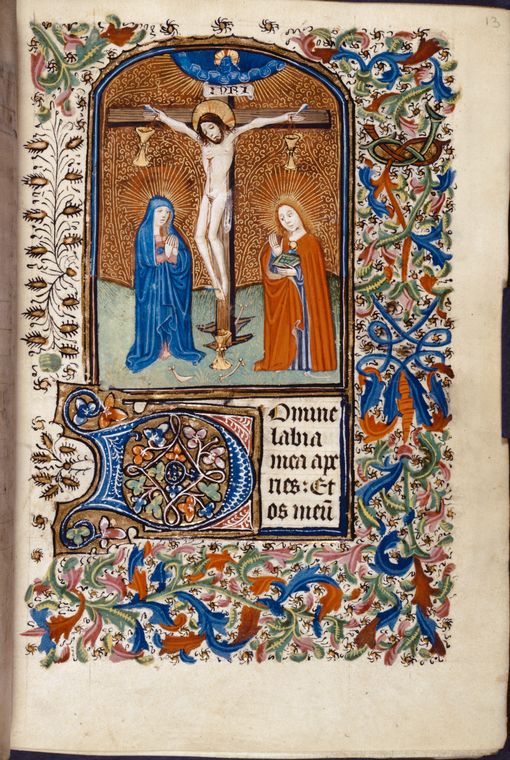

But that’s not all, oh no! The complete archive, titled simply and authoritatively “Sounds,” also houses recordings of accents and dialects, environment and nature, pop music, “sound maps,” oral history, classical music, sound recording history, and arts, literature, and performance (such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s short discourse on “Wireless,” animated in the video below).

The 80,000 recordings available to stream online represent just a selection of the British Library’s “extensive collections of unique sound recordings,” but what a selection it is. In the short video at the top of the post, The Wire Magazine takes us on a mini-tour of the physical archive’s meticulous digitization methods. As with all such wide-ranging collections, it’s difficult to know where to begin.

One might browse the range of unusual folk sounds on aural display in the World & Traditional music section, covering every continent and a daunting metacategory called “Worldwide.” For a more specific entry point, Electronic Beats recommends a collection of “around 8,000 Afropop tracks” from Guinea, recorded on “the state-supported Syliphone label” and “released between 1958 and 1984.”

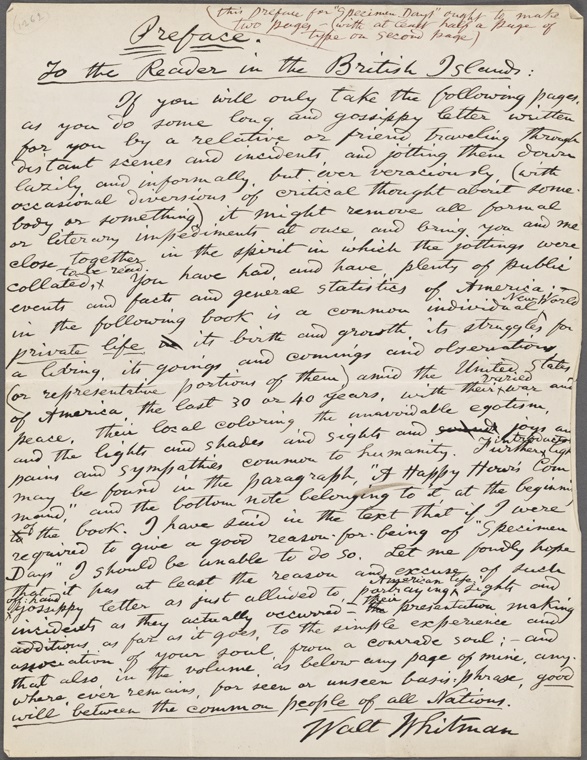

Other highlights include “Between Two Worlds: Poetry & Translation,” an ongoing project begun in 2008 that features readings and interviews with “poets who are bilingual or have English as a second language, or who otherwise reflect the project’s theme of dual cultures.” Or you may enjoy the extensive collection of classical music recordings, including “Hugh Davies experimental music,” or the “Oral History of Jazz in Britain.”

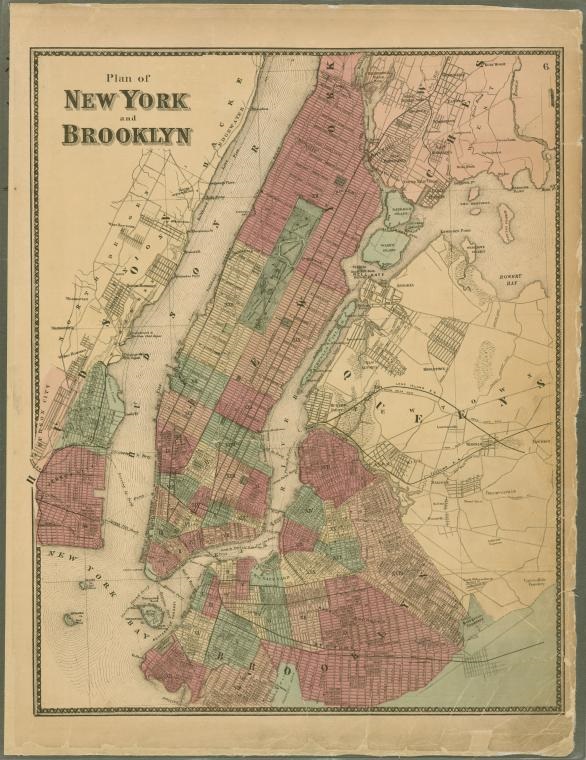

The category called “Sound Maps” organizes a diversity of recordings—including regional accents, interviews with Holocaust survivors, wildlife sounds, and Ugandan folk music—by reference to their locations on Google maps.

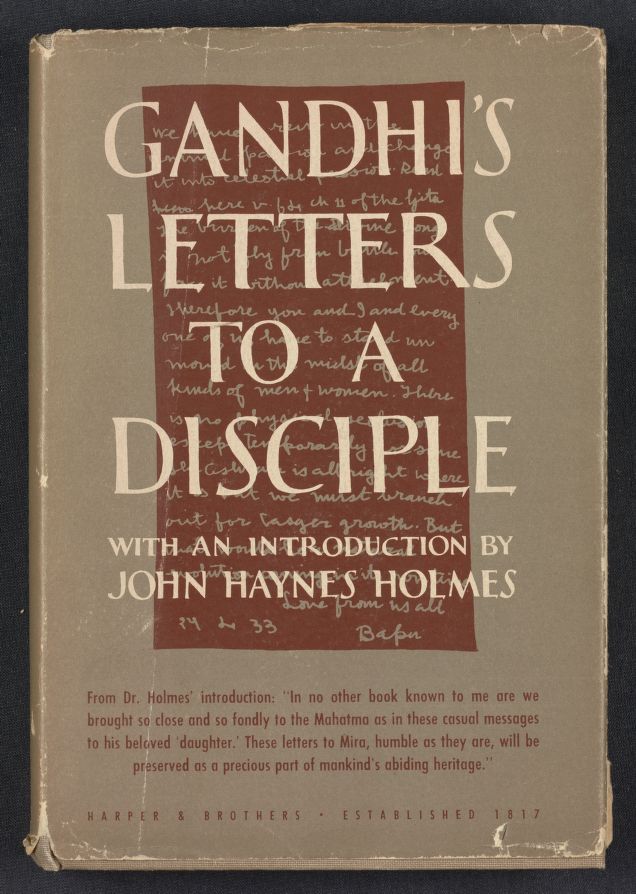

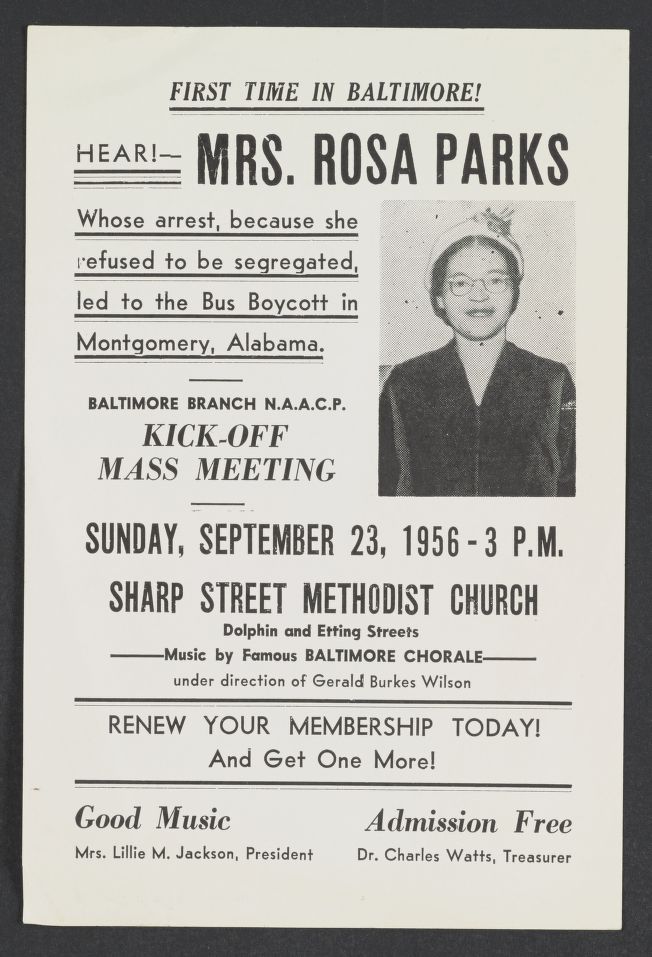

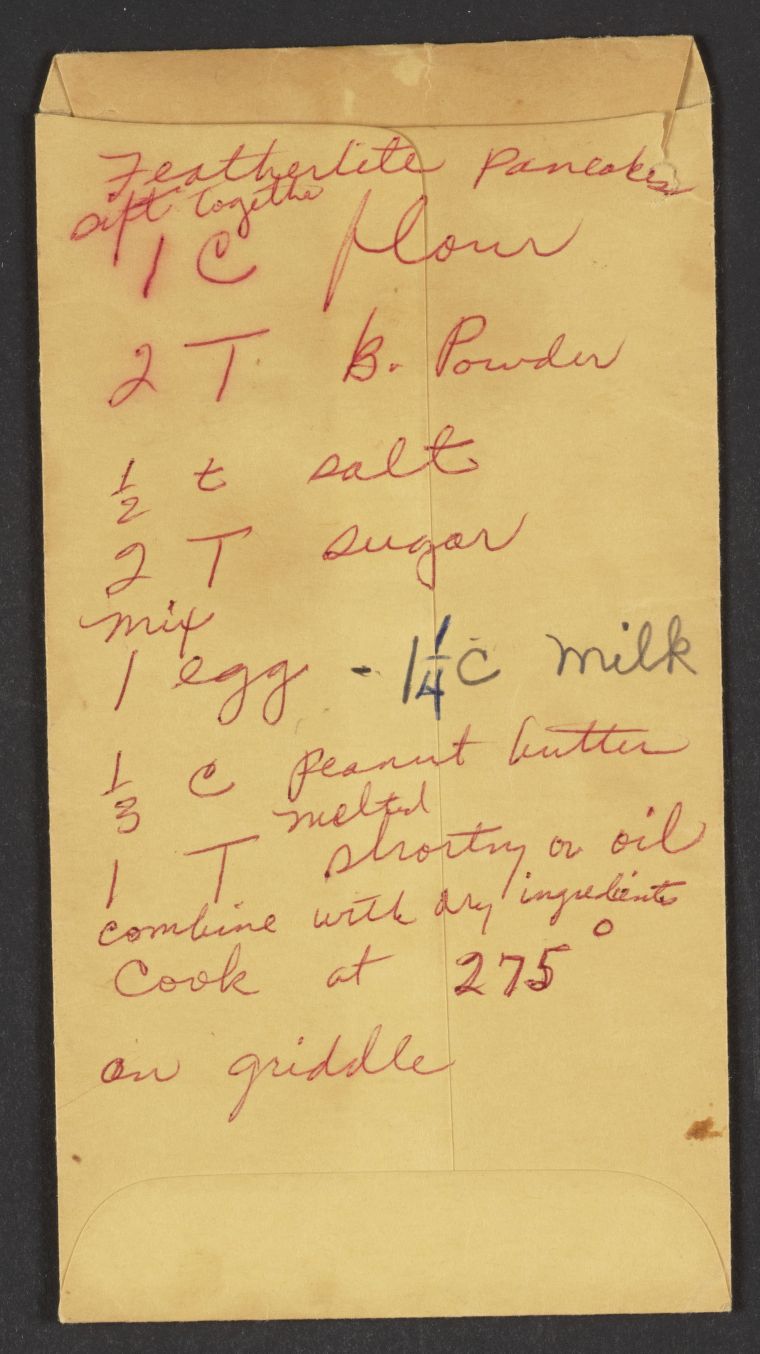

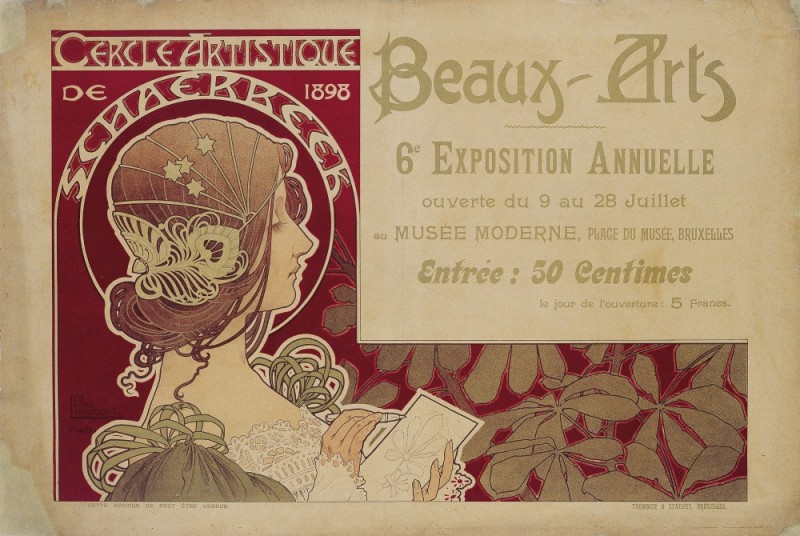

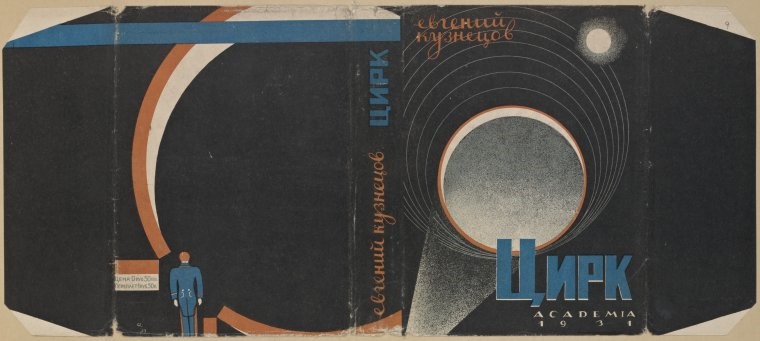

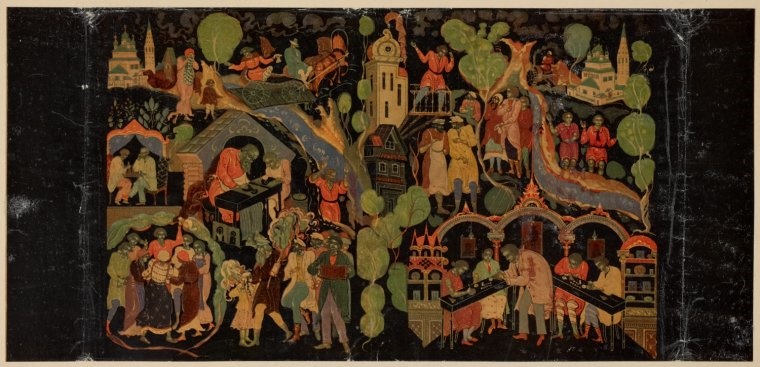

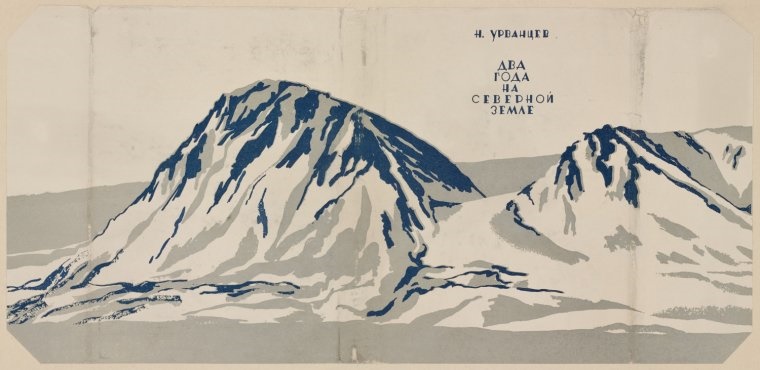

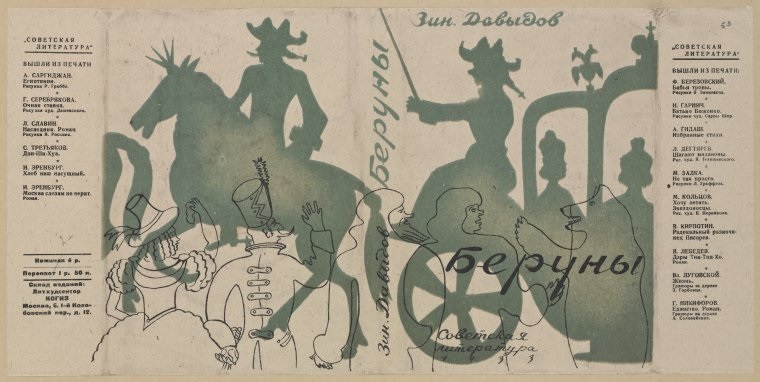

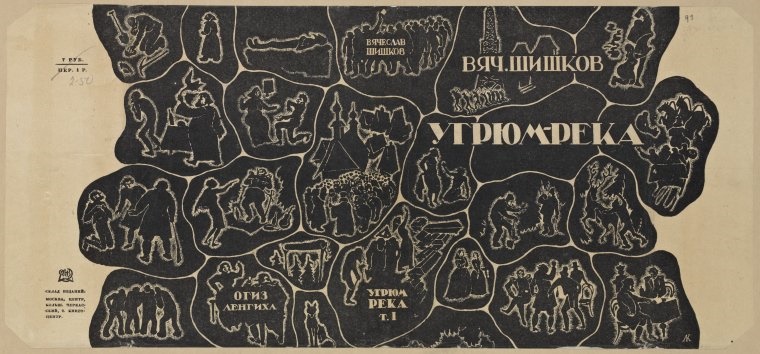

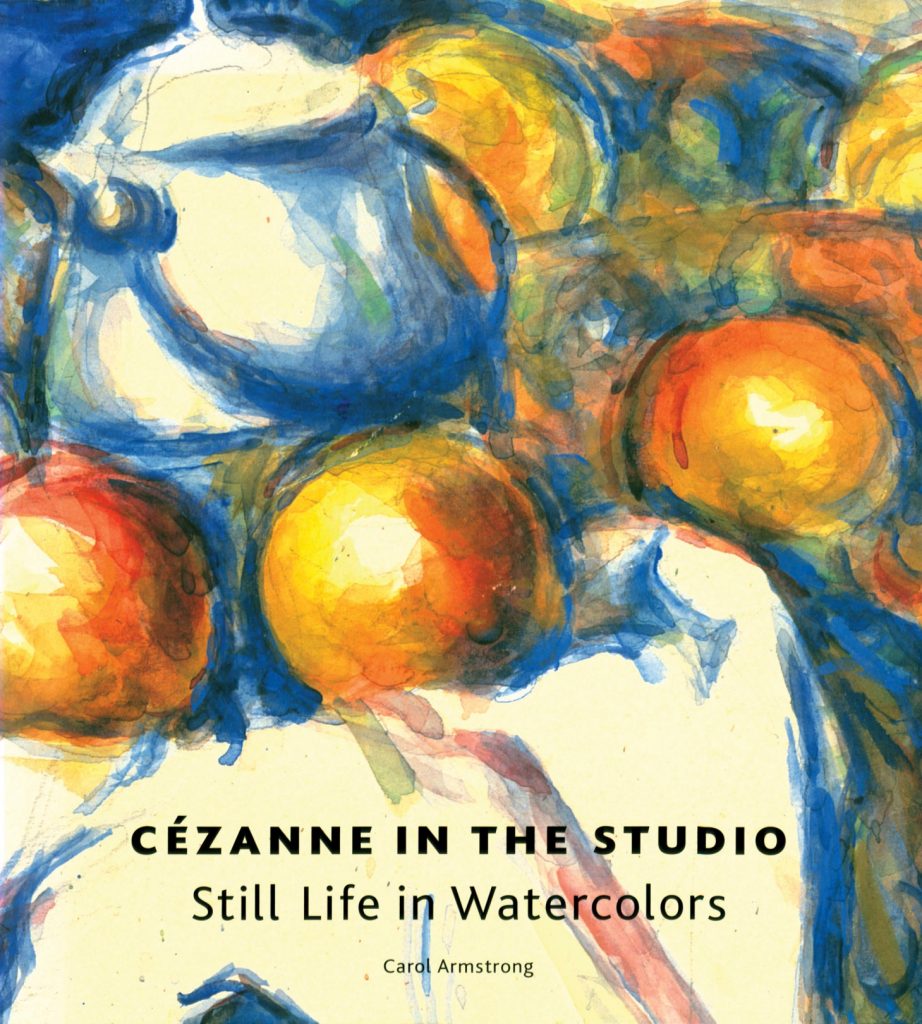

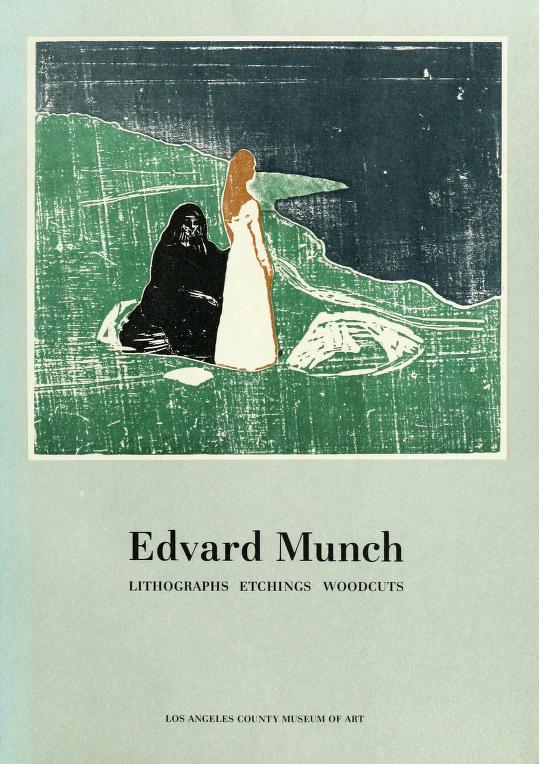

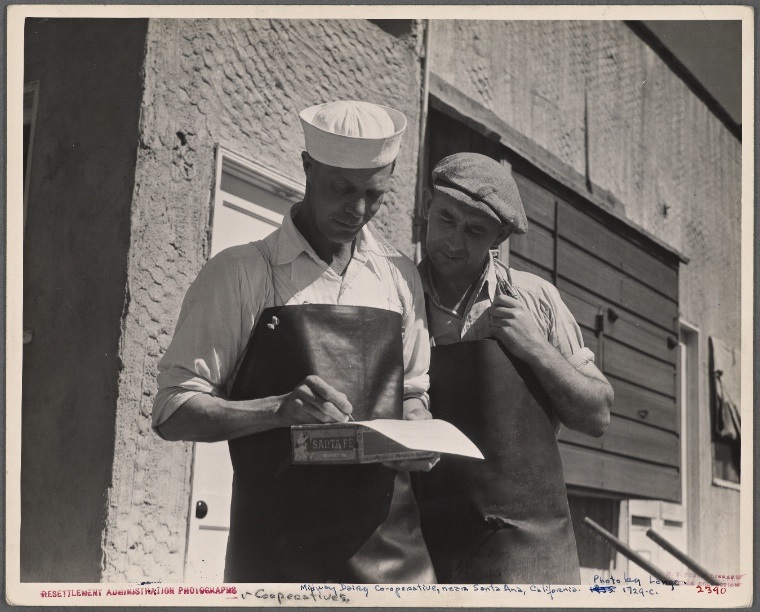

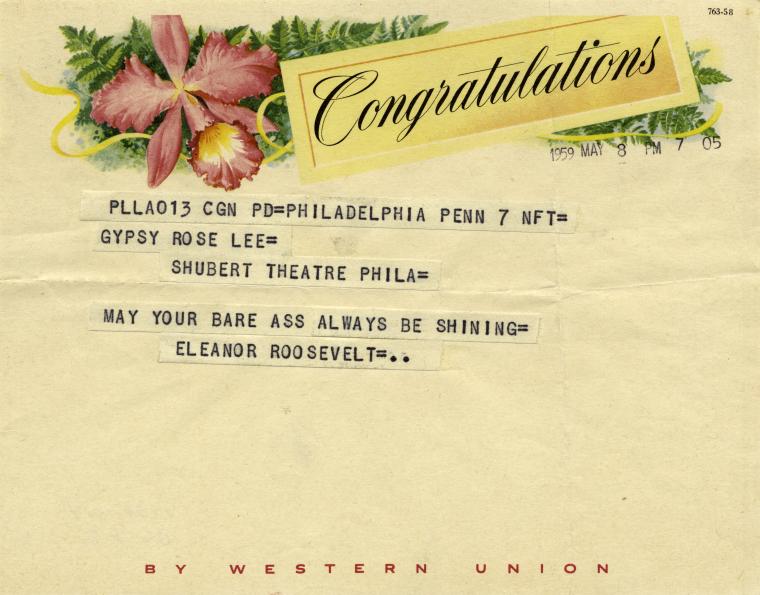

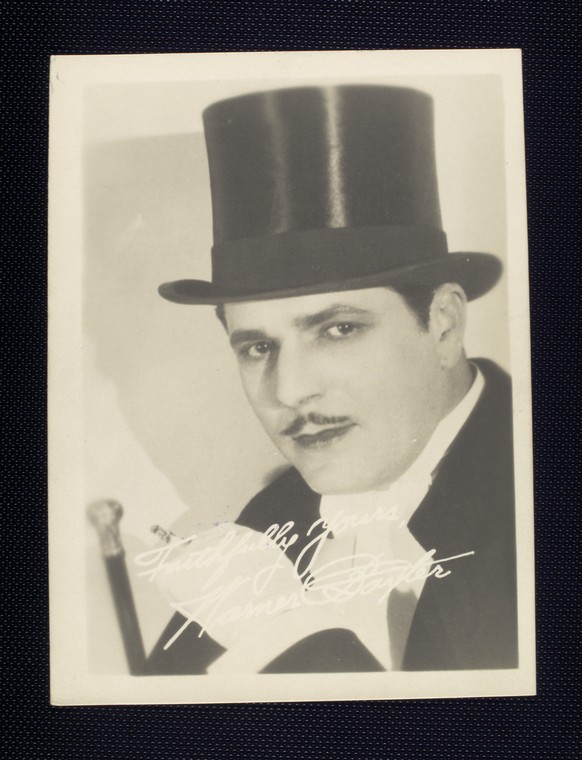

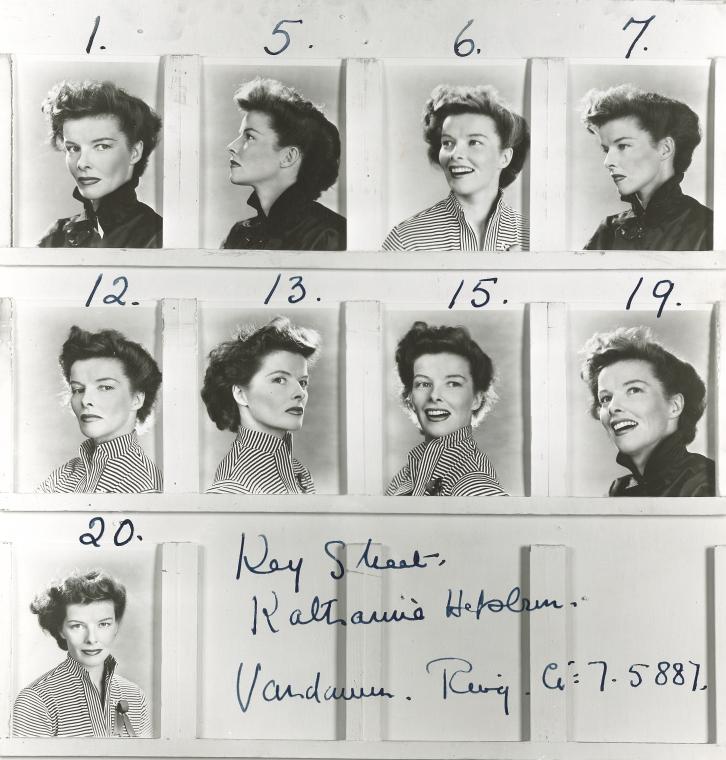

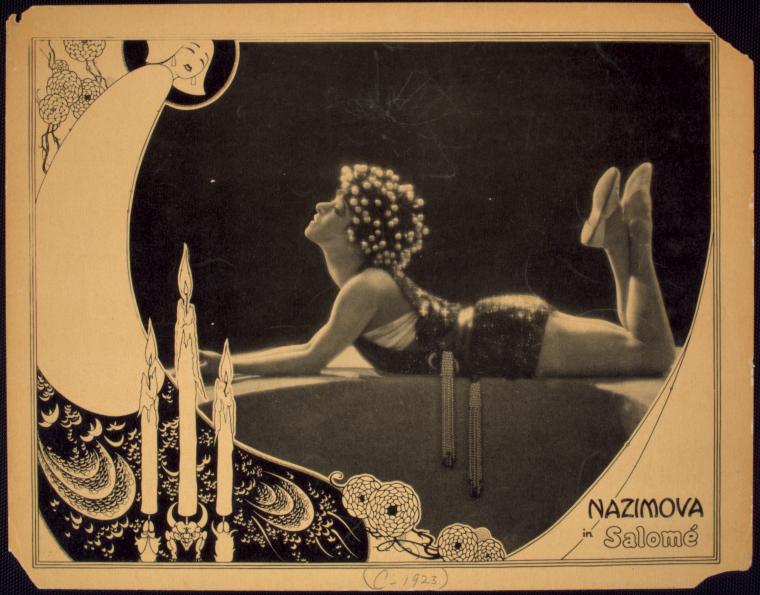

Not all of the material in “Sounds” is sound-based. Recording and audio geeks and historians will appreciate the large collection of “Playback & Recording Equipment” photographs (such as the 1912 Edison Disc Phonograph, above ), spanning the years 1877 to 1992. Also, many of the recordings—such as the wonderful first version of “Dirty Old Town” by Alan Lomax and the Ramblers, with Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger (below)—feature album covers, front and back, as well as disc labels.

The recordings in the Archive are unfortunately not downloadable (unless you are a licensed member of a UK HE/FE institution), but you can stream them all online and share any of them on your favorite social media platform. Perhaps the British Library will extend download privileges to all users in the future. For now, browsing through the sheer volume and variety of sounds in the archive should be enough to keep you busy.

Related Content:

The Alan Lomax Sound Archive Now Online: Features 17,000 Blues & Folk Recordings

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness