In his 1686 Principia Mathematica, Isaac Newton elaborated not only his famous Law of Gravity, but also his Three Laws of Motion, setting a centuries-long trend for scientific three-law sets. Newton’s third law has by far proven his most popular: “every action has an equal and opposite reaction.” In Arthur C. Clarke’s 20th century Three Laws, the third has also attained wide cultural significance. No doubt you’ve heard it: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

Clarke’s third law gets invoked in discussions of the so-called “demarcation problem,” that is, of the boundaries between science and pseudoscience. It also comes up, of course, in science fiction forums, where people refer to Ted Chiang’s succinct interpretation: “If you can mass-produce it, it’s science, and if you can’t, it’s magic.” This makes sense, given the central importance the sciences place on reproducibility. But in Newton’s pre-industrial age, the distinctions between science and magic were much blurrier than they are now.

Newton was an early fellow of the British Royal Society, which codified repeatable experiment and demonstration with their motto, “Nothing in words,” and published the Principia. He later served as the Society’s president for over twenty years. But even as the foremost representative of early modern physics—what Edward Dolnick called “the clockwork universe”—Newton held some very strange religious and magical beliefs that we would point to today as examples of superstition and pseudoscience.

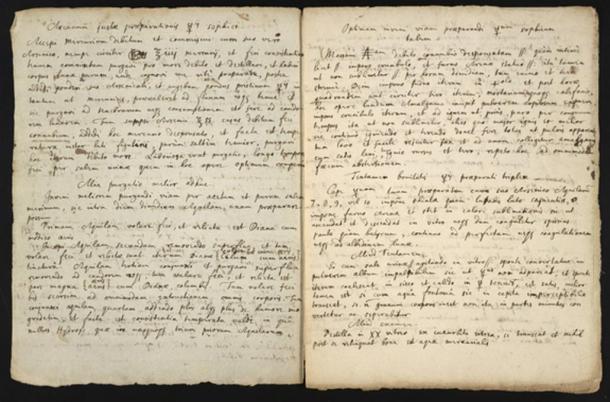

In 1704, for example, the year after he became Royal Society president, Newton used certain esoteric formulae to calculate the end of the world, in keeping with his long-standing study of apocalyptic prophecy. What’s more, the revered mathematician and physicist practiced the medieval art of alchemy, the attempt to turn base metals into gold by means of an occult object called the “Philosopher’s stone.” By Newton’s time, many alchemists believed the stone to be a magical substance composed in part of “sophick mercury.” In the late 1600s, Newton copied out a recipe for such stuff from a text by American-born alchemist George Starkey, writing his own notes on the back of the document.

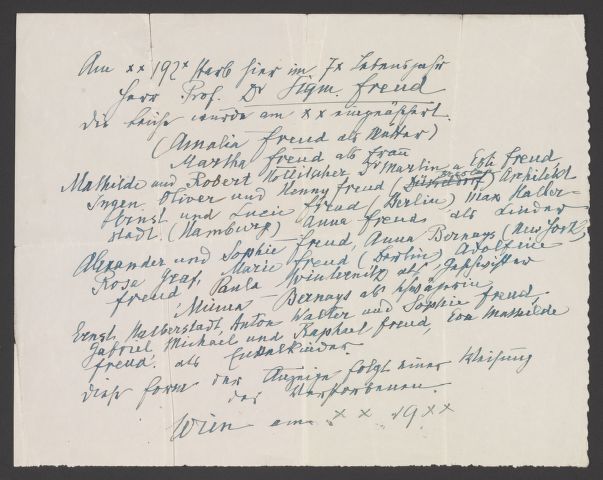

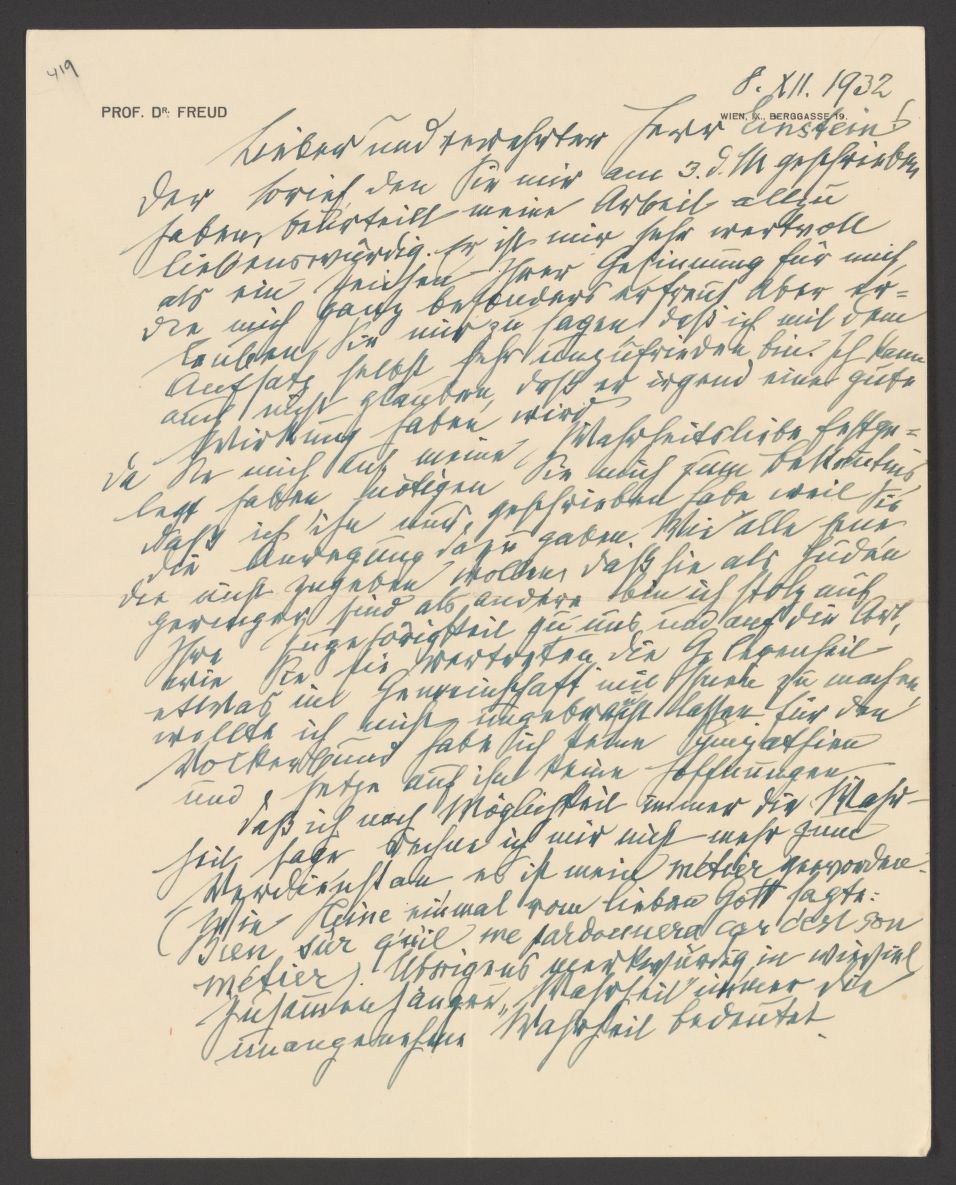

You can see the “sophick mercury” formula in Newton’s hand at the top. The recipe contains, in part, “Fiery Dragon, some Doves of Diana, and at least seven Eagles of mercury,” notes Michael Greshko at National Geographic. Newton’s alchemical texts detail what has long been “dismissed as mystical pseudoscience full of fanciful, discredited processes.” This is why Cambridge University refused to archive Newton’s alchemical papers in 1888, and why his 1855 biographer wondered how he could be taken in by “the obvious production of a fool and a knave.” Newton’s alchemy documents passed quietly through many private collectors’ hands until 1936, when “the world of Isaac Newton scholarship received a rude shock,” writes Indiana University’s online project, The Chymistry of Isaac Newton:

In that year the venerable auction house of Sotheby’s released a catalogue describing three hundred twenty-nine lots of Newton’s manuscripts, mostly in his own handwriting, of which over a third were filled with content that was undeniably alchemical.

Marked “not to be printed” upon his death in 1727, the alchemical works “raised a host of interesting questions in 1936 as they do even today.” Those questions include whether or not Newton practiced alchemy as an early scientific pursuit or whether he believed in a “secret theological meaning in alchemical texts, which often describe the transmutational secret as a special gift revealed by God to his chosen sons.” The important distinction comes into play in Ted Chiang’s discussion of Clarke’s Third Law:

Suppose someone says she can transform lead into gold. If we can use her technique to build factories that turn lead into gold by the ton, then she’s made an incredible scientific discovery. If on the other hand it’s something that only she can do… then she’s a magician.

Did Newton think of himself as a magician? Or, more properly given his religiosity, as God’s chosen vessel for alchemical transformation? It’s not entirely clear what he believed about alchemy. But he did take the practice of what was then called “chymistry” as seriously as he did his mathematics. James Voelkel, curator of the Chemical Heritage Foundation—who recently purchased the Philosophers’ stone recipe—tells Livescience that its author, Starkey, was “probably American’s first renowned, published scientist,” as well as an alchemist. While Newton may not have tried to make the mercury, he did correct Starkey’s text and write his own experiments for distilling lead ore on the back.

Indiana University science historian William Newman “and other historians,” notes National Geographic, “now view alchemists as thoughtful technicians who labored over their equipment and took copious notes, often encoding their recipes with mythological symbols to protect their hard-won knowledge.” The occult weirdness of alchemy, and the strange pseudonyms its practitioners adopted, often constituted a means to “hide their methods from the unlearned and ‘unworthy,’” writes Danny Lewis at Smithsonian. Like his fellow alchemists, Newton “diligently documented his lab techniques” and kept a careful record of his reading.

“Alchemists were the first to realize that compounds could be broken down into their constituent parts and then recombined,” says Newman, a principle that influenced Newton’s work on optics. It is now acknowledged that—while still considered a mystical pseudoscience—alchemy is an important “precursor to modern chemistry” and, indeed, as Indiana University notes, it contributed significantly to early modern pharmacology” and “iatrochemistry… one of the important new fields of early modern science.” The sufficiently advanced technology of chemistry has its origins in the magic of “chymistry,” and Newton was “involved in all three of chymistry’s major branches in varying degrees.”

Newton’s alchemical manuscript papers, such as “Artephius his secret Book” and “Hermes” sound nothing like what we would expect of the discoverer of a “clockwork universe.” You can read transcriptions of these manuscripts and several dozen more at The Chymistry of Isaac Newton, where you’ll also find an Alchemical Glossary, Symbol Guide, several educational resources, and more. The manuscripts not only show Newton’s alchemy pursuits, but also his correspondence with other early modern alchemical scientists like Robert Boyle and Starkey, whose recipe—titled “Preparation of the [Socphick] Mercury for the [Philosophers’] stone by the Antinomial Stellate Regulus of Mars and Luna from the Manuscripts of the American Philosopher”—will be added to the Indiana University online archive soon.

Related Content:

In 1704, Isaac Newton Predicts the World Will End in 2060

Sir Isaac Newton’s Papers & Annotated Principia Go Digital

Isaac Newton Creates a List of His 57 Sins (Circa 1662)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness