Image by Andrew Rusk, via Wikimedia Commons

If you’re a linguist, you’ve read Noam Chomsky—no way of getting around that. There may be reasons to disagree with Chomsky’s linguistic theories but—as Newton’s theories do in physics—his breakthroughs represent a paradigmatic shift in the study of language, an implicit or explicit reference point for nearly every linguistic analysis in the past few decades.

If you’re on the political left, you’ve read Chomsky, or you should. Even if there are significant reasons to disagree with whatever controversial stance he’s taken over the years, few political theorists have approached their subject with the degree of doggedness, intellectual integrity, and erudition as he has. Chomsky began his second career as a political activist and philosopher in the late sixties, speaking out in opposition to the Vietnam war. Since then, he’s written majorly influential works on mass media propaganda, Cold War politics and interventionist war, economic imperialism, anarchism, etc.

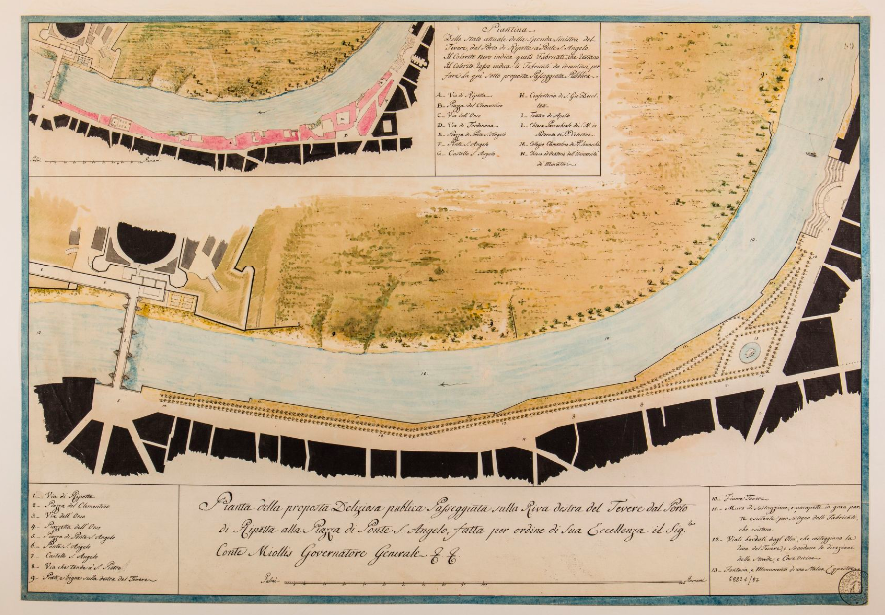

Now an emeritus professor from MIT, where he began teaching in 1955, and a laureate professor at the University of Arizona, Chomsky has reached that stage in every public intellectual’s career when archivists and curators begin consolidating a documentary legacy. Librarians at MIT started doing so a few years ago when, in 2012, the MIT Libraries Institute Archives received over 260 boxes of Chomsky’s personal papers. You can hear the man himself discuss the archive’s importance in the short interview at the top. And at the MIT Library site unBox Chomsky Archive, you’ll find slideshow previews of its contents.

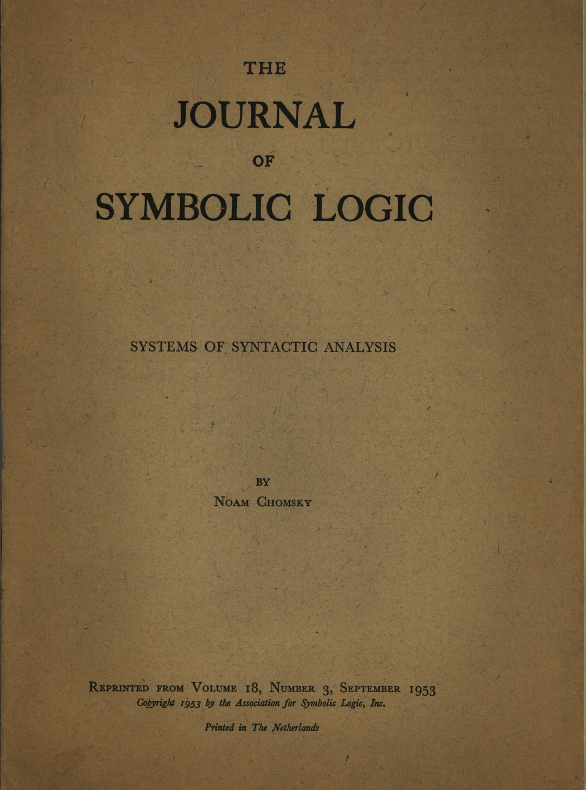

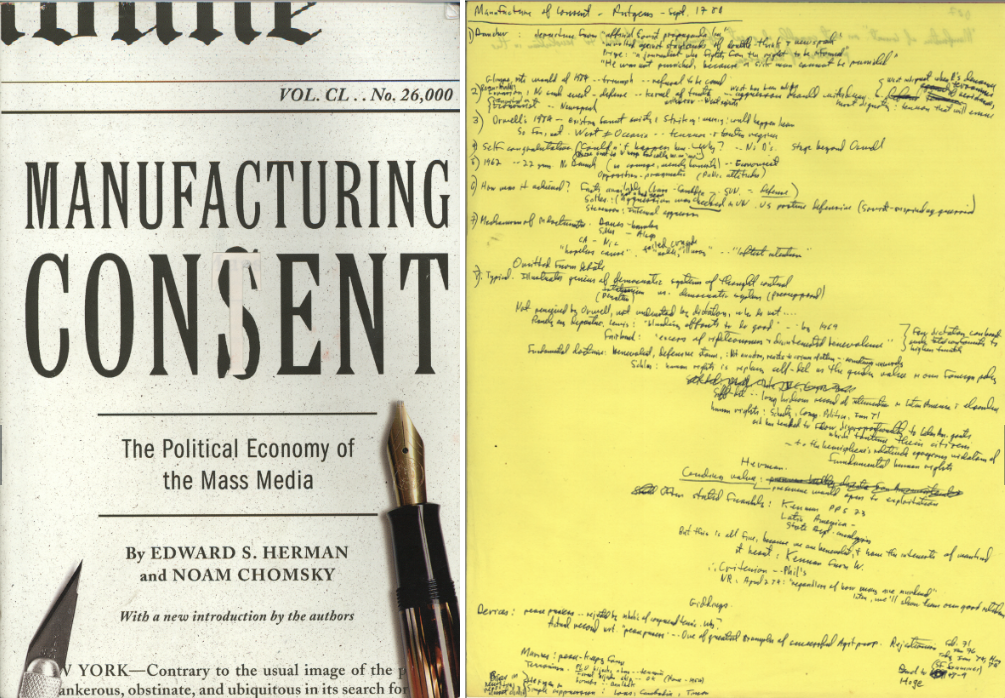

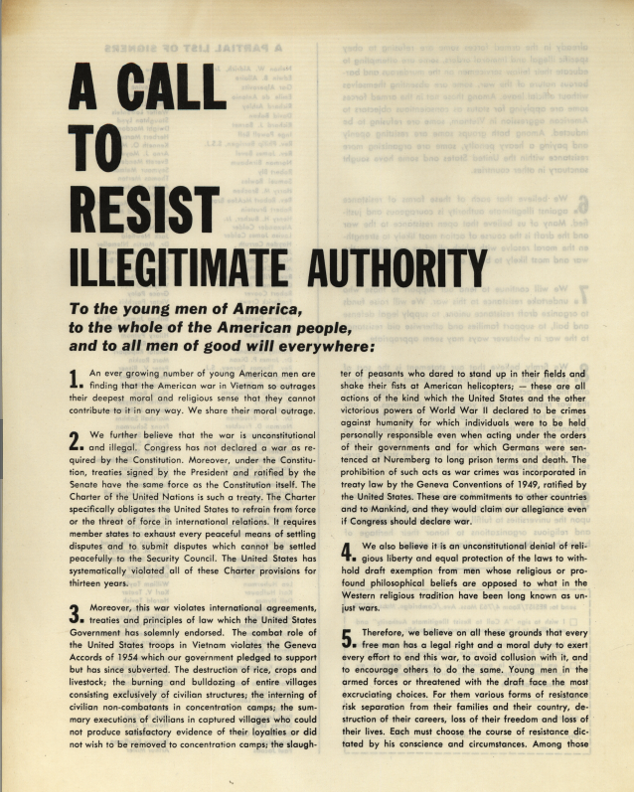

Those contents include the 1953 paper “Systems of Syntactic Analysis,” which “appears to be Chomsky’s first foray in print of what would become transformational generative grammar.” Also archived are notes from a 1984 talk on “Manufacturing Consent” given at Rutgers University, outlining the ideas Chomsky and Edward S. Herman would fully explore in the 1988 book of the same name on “the political economy of the mass media.” And in the category of “activism,” we find materials like the newsletter below, published by an anti-war organization Chomsky co-founded in the 60s called RESIST.

MIT hopes to “digitize the hundreds of thousands of pieces” in the collection, “to make it accessible to the public.” Such a massive undertaking exceeds the library’s budget, so they have asked for financial support. At unBoxing the Chomsky Archive, you can make a donation, or just peruse the slideshow previews and consider the legacy of one of the U.S.’s most formidable living scientific and political thinkers.

Related Content:

Read 9 Free Books By Noam Chomsky Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness