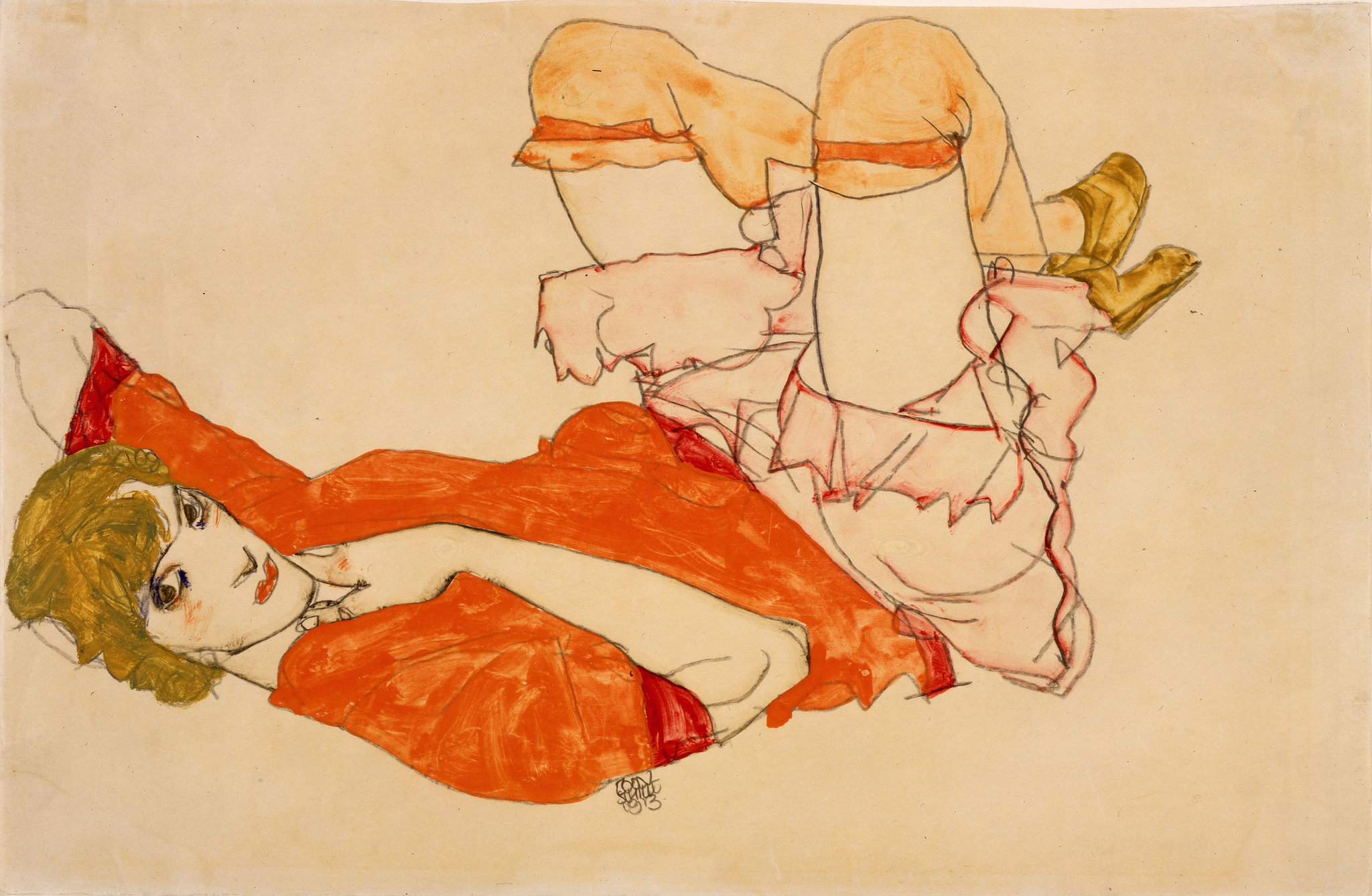

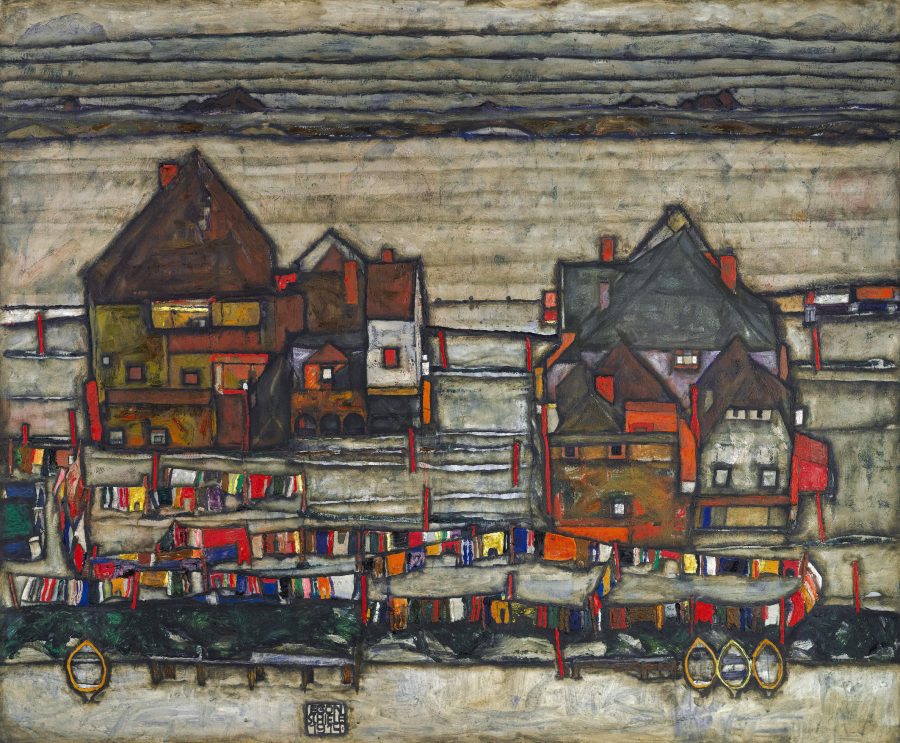

If you’ve ever mistaken an Egon Schiele for a Gustav Klimt, you can surely be forgiven—the Austrian modernist don served as a North Star for Schiele, who sought out Klimt, apprenticed himself, and received a great deal of encouragement from his elder. But he would soon strike out on his own, developing a grotesque, exaggerated, yet elegantly sensual style that shocked his contemporaries and made him a leading figure of Austrian Expressionism.

Now, a century after his death in 1918 at age 28, a number of exhibitions have highlighted the complexity of his brief career, during which he “created a formidable output that turned him into a real icon for new generations,” writes Elena Martinique.

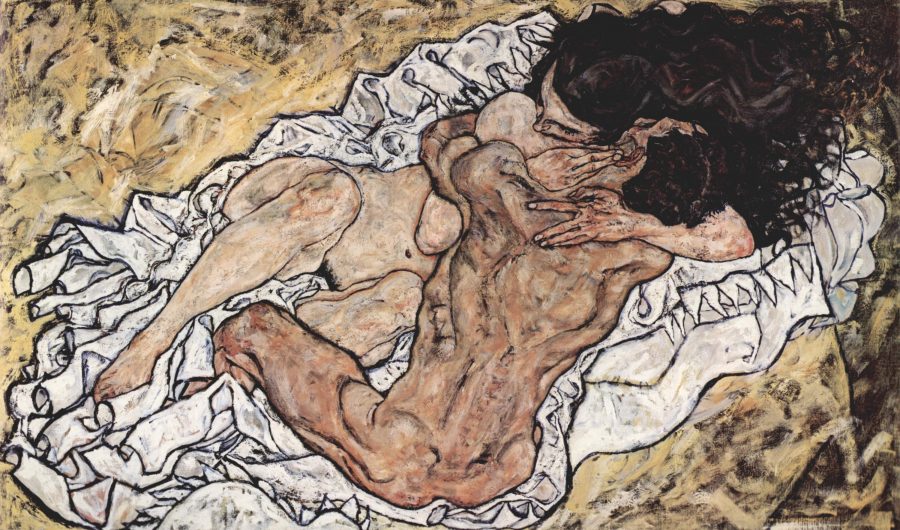

Schiele achieved “a remarkable impact and permanency” and it’s easy to see why. Best known for his erotic, elongated portraits and self-portraits, “searing explorations of their sitter’s psyches,” as The Art Story describes them, his depictions of the human form are considered some of the “most remarkable of the 20th century.”

The details of Schiele’s short life paint the picture of a modernist rock star. He is as famous for his work as for his “licentious lifestyle… marked by scandal, notoriety, and a tragically early death… at a time when he was on the verge of the commercial success that had eluded him for much of his career.” In his short life, Martinique notes, Schiele produced “over 400 paintings; close to 3,000 watercolors and drawings; 21 sketchbooks; 17 graphics; and 4 sculptures.”

This incredible body of work will be made available in full online in a project spearheaded by Jane Kallir, co-director of New York’s Galerie St. Etienne, which mounted Schiele’s first American solo exhibition in 1941 and recently staged a “comprehensive survey of the artist’s artistic development.” Kallir authored the most recent catalogue raisonné of Schiele’s work, and rather than publish another print edition, she has decided to put the full catalogue online, under the auspices of her research institute.

The project currently “details 419 works and counting, with a particular emphasis on Schiele’s paintings,” reports Meilan Solly at Smithsonian. His drawings and watercolors will be added in 2019. Though it is a public resource, the online catalogue is designed for scholars, who can use it to “trace specific pieces’ provenance or debunk the existence of forgeries.” Kallir continues the work of her grandfather, Otto Kallir, who wrote the first complete catalogue of the artist’s work in 1930.

That early reference has proven invaluable “in the tangle courtroom drama surrounding the restitution of Nazi-looted art.” The centenary of Schiele’s death on October 31, 2018 has brought even more interest to his work, and a rise in fakes circulating in the art market. “It is very important to have a reliable and readily accessible means of identifying authentic works of art,” Kallir writes in a statement. There is no one better placed than her to create it.

But while the Kallir Research Institute’s Complete Works of Egon Schiele Online offers necessary information for curators, art dealers, and scholars, it is very accessible to the general public. If you’re new to Schiele, start with a short biography at the site. (Also read The Art Story’s overview and see several high-resolution scans of his most famous works at the Art History Project). Then click on “Works” to view photos and information about sketchbooks, graphics, sculptures, and paintings.

These latter works show a radical development: from the conservative, traditional style of his earliest painting, to the heavily Klimt-influenced work of 1908–9, to 1910–18, when he discovered and perfected his own peculiar vision.

Related Content:

Explore 7,600 Works of Art by Edvard Munch: They’re Now Digitized and Free Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.