All images here by David Romero

From the humblest home renovator to the mightiest auteur of skyscrapers, every architect shares the common experience of not building their projects. This is true even of Frank Lloyd Wright himself: in his lifetime he created 1,171 architectural works, 660 of which went unrealized. How those never-built Wright designs would have fared in the physical realm has been a topic of great interest for the architect’s generation upon generation of fans.

But one lover of Wright’s work has gone well beyond speculation, creating faithful, photorealistic 3D renderings of these nonexistent structures, a few of which you can see at the site of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Notably, the digital artist paying such painstaking homage to this most American of all architects hails from Spain. David Romero is the creator of the site Hooked on the Past, a showcase of his various architectural renderings.

“The project started in 2018, when the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation commissioned Romero to render some of the architect’s most ambitious works for its quarterly magazine,” writes Smithsonian’s Molly Enking. “Each series of images corresponds with a different theme — like designs related to automobiles. Most recently, Romero tackled several of Wright’s unrealized skyscraper projects for the foundation.”

Romero’s most ambitious undertaking thus far has been his rendering of Broadacre City, Wright’s design for an entire urban-rural utopia previously featured here on Open Culture. “Modeling Broadacre took me over eight months,” he tells the FLWF. “The virtual model contains more than one hundred buildings, of which all the exterior facades have been modeled, including their doors and windows. There also are one hundred ships, two hundred ‘aerotors,’ 5,800 cars, and more than 250,000 trees in the virtual model,” each made of “hundreds of thousands of three-dimensional polygons.”

Even though Wright left behind a fairly rich set of materials documenting his plans for Broadacre City, Romero had to draw from other sources both to fill out the surrounding landscape (Midwestern, por supuesto) and to create a properly “retro-futuristic” ambience. “A reference that seemed especially relevant to me was the Dymaxion Car by Buckminster Fuller,” he says, “a design that has points in common with Wright’s ideas.”

The near-fantastical Broadacre City would probably have been unbuildable at any point in history, but others would also face serious challenges today: “For example, in the Trinity Chapel Wright designed beautiful access ramps with a single constant slope throughout its path. This design, perfectly valid in 1958, would not meet today the requirements of the ADA code and the design would lose the elegance of its simplicity.”

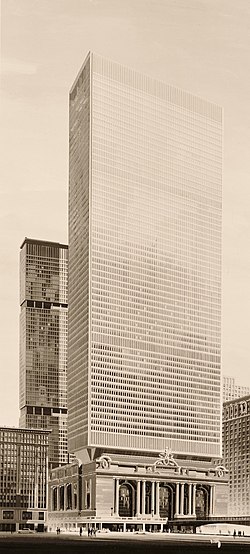

Romero has also brought to digital life a range of Wright’s other demolished or never-built projects including the Thomas C. Lea House, the Arizona Capitol Building, the Lake Tahoe Summer Colony (featuring cabins that appear to float in the water), the massive National Life Insurance Building, and the Universal Portland Cement Co. Exhibition Pavilion. Given the work Romero and his collaborators (including no few fellow enthusiasts with keen eyes for inaccurate-looking details) have put in, Frank Lloyd Wright would surely recognize more than a few of his own visions in the results — and in the project itself, something of his own ambition.

via Smithsonian Magazine/Messy Nessy

Related content:

Frank Lloyd Wright Designs an Urban Utopia: See His Hand-Drawn Sketches of Broadacre City (1932)

What Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unusual Windows Tell Us About His Architectural Genius

When Frank Lloyd Wright Designed a Doghouse, His Smallest Architectural Creation (1956)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.