In 1880, architect Thomas W. Cutler endeavored to introduce his fellow Brits to Japanese art and design, a subject that remained novel for many Westerners of the time, given how recently the Tokugawa shogunate had “kept themselves aloof from all foreign intercourse, and their country jealously closed against strangers.”

Having written positively of China’s influence on Japanese artists, Cutler hoped that access to Western art would not prove a corrupting factor:

The fear that a bastard art of a very debased kind may arise in Japan, is not without foundation…The European artist, who will study the decorative art of Japan carefully and reverently, will not be in any haste to disturb, still less to uproot, the thought and feeling from which it has sprung; it is perhaps the ripest and richest fruit of a tree cultivated for many ages with the utmost solicitude and skill, under conditions of society peculiarly favorable to its growth.

Having never visited Japan himself, Cutler relied on previously published works, as well as numerous friends who were able to furnish him with “reliable information upon many subjects,” given their “long residence in the country.”

Accordingly, expect a bit of bias in A Grammar of Japanese Ornament and Design (1880).

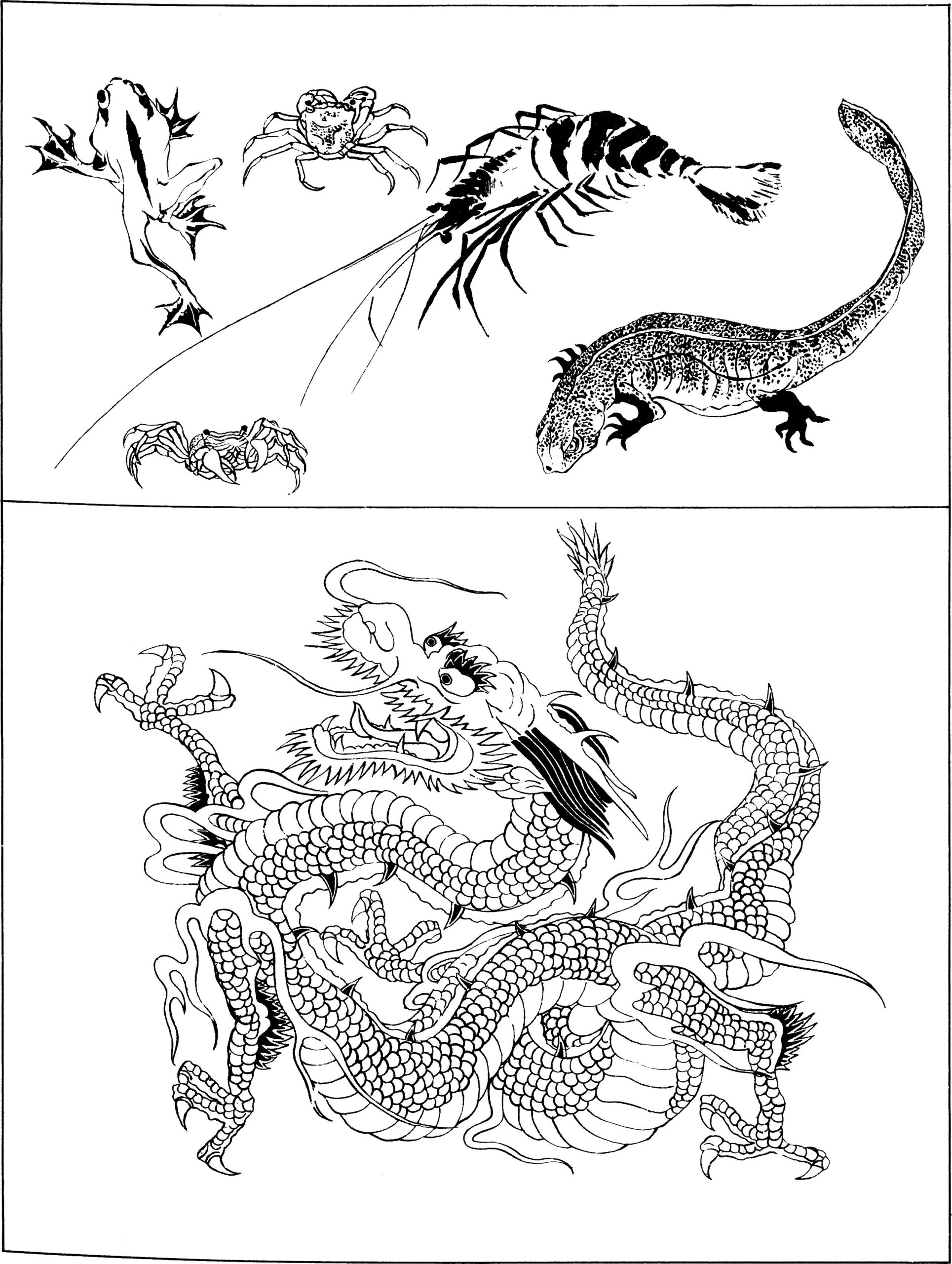

That said, Cutler emerges as a robust admirer of Japan’s painting, lacquerware, ceramics, calligraphy, textiles, metalwork, enamelwork and netsuke carvings, the latter of which are “are often marvelous in their humor, detail, and even dignity.”

Only Japan’s wooden architecture, which he confidently pooh poohed as little more than “artistic carpentry, decoration, and gardening”, cleverly designed to withstand earthquakes, get shown less respect.

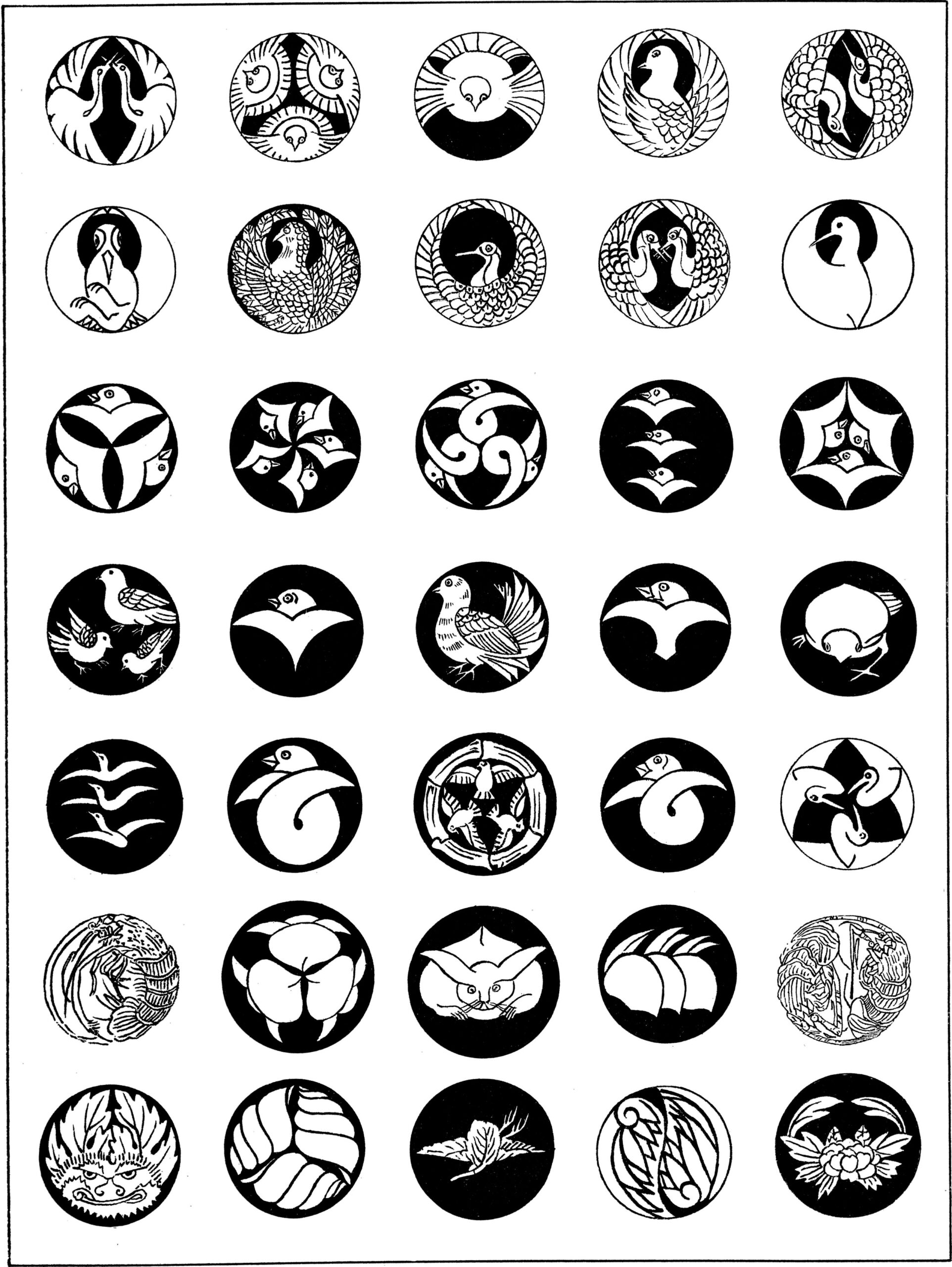

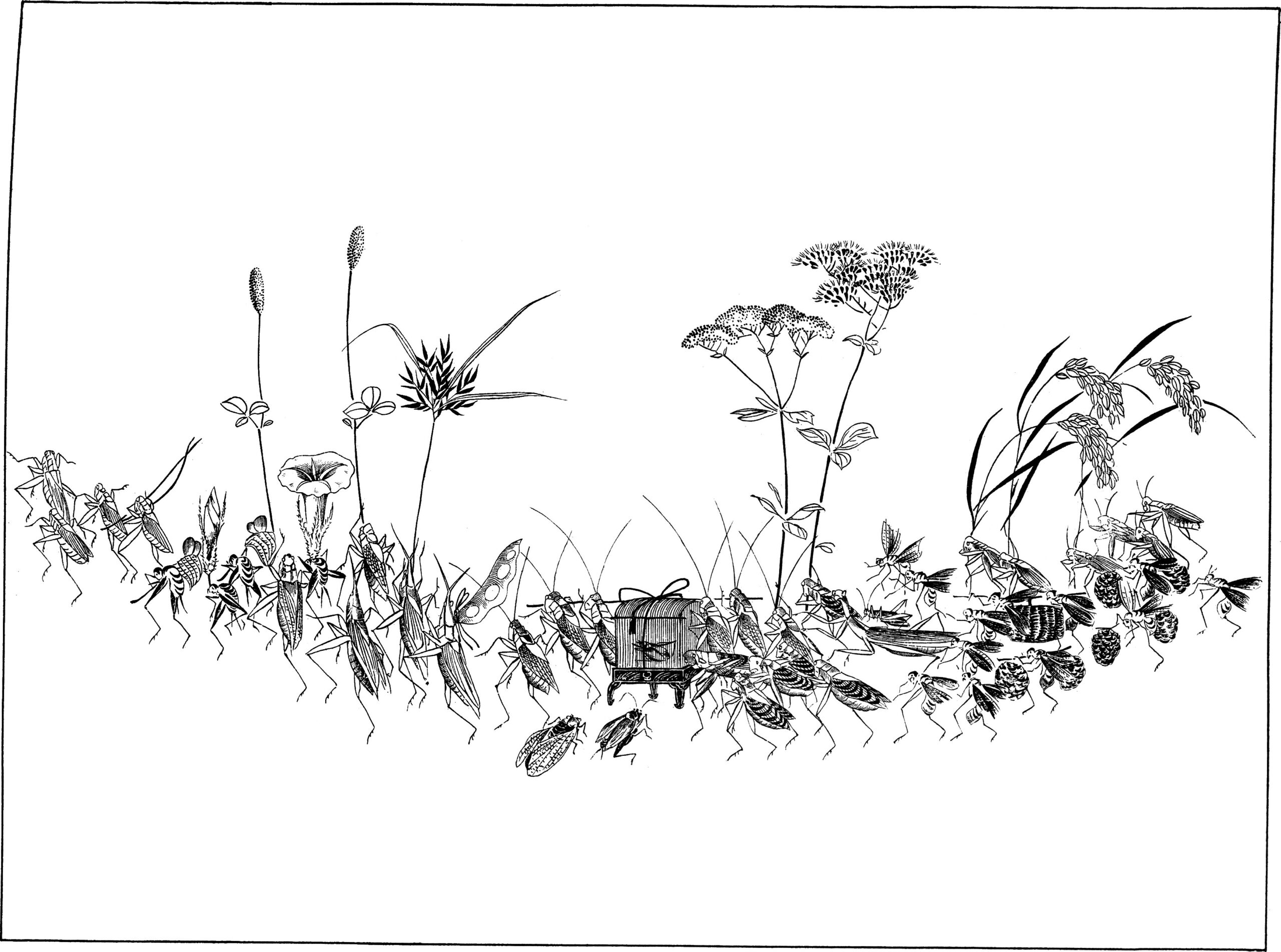

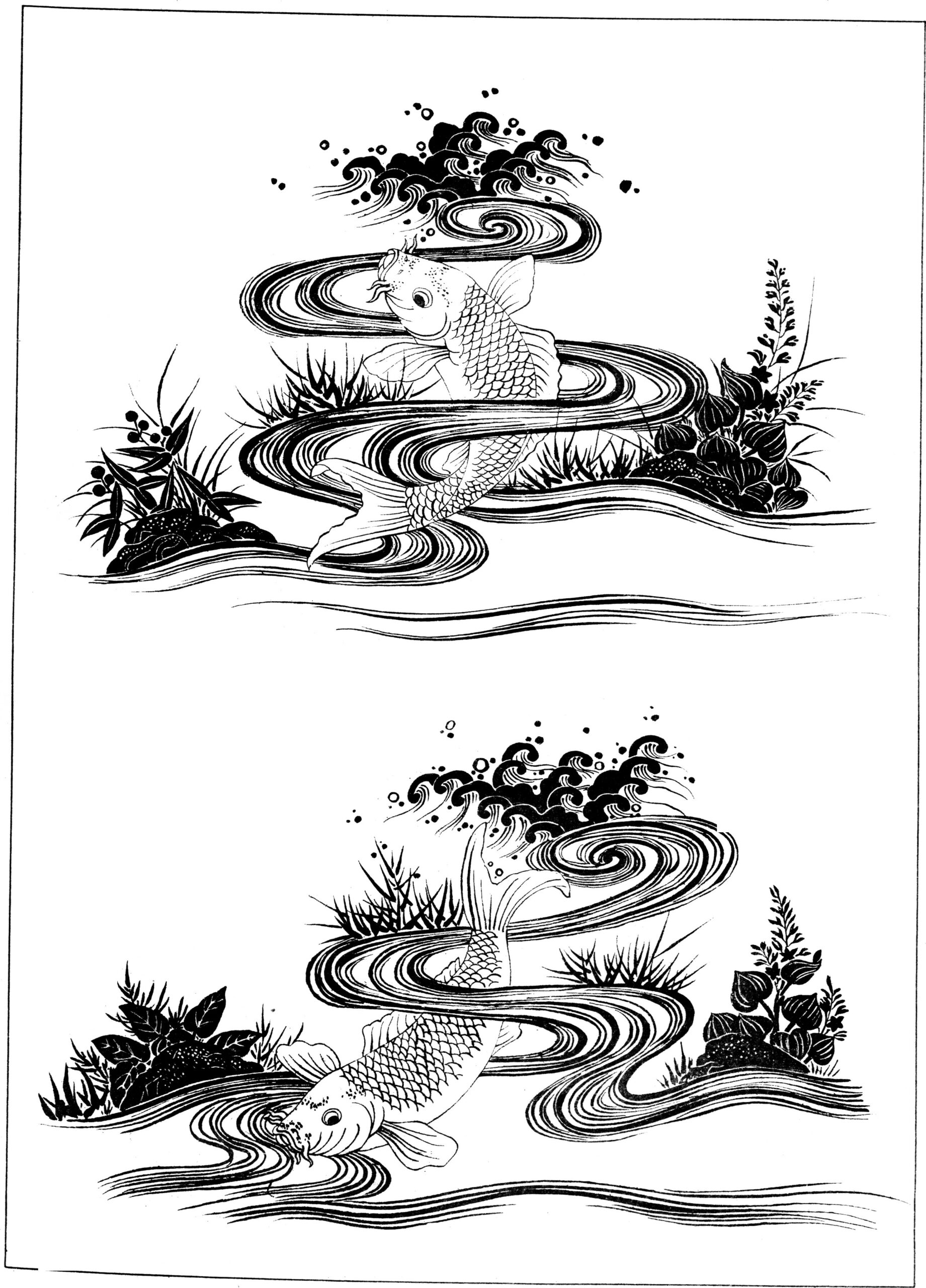

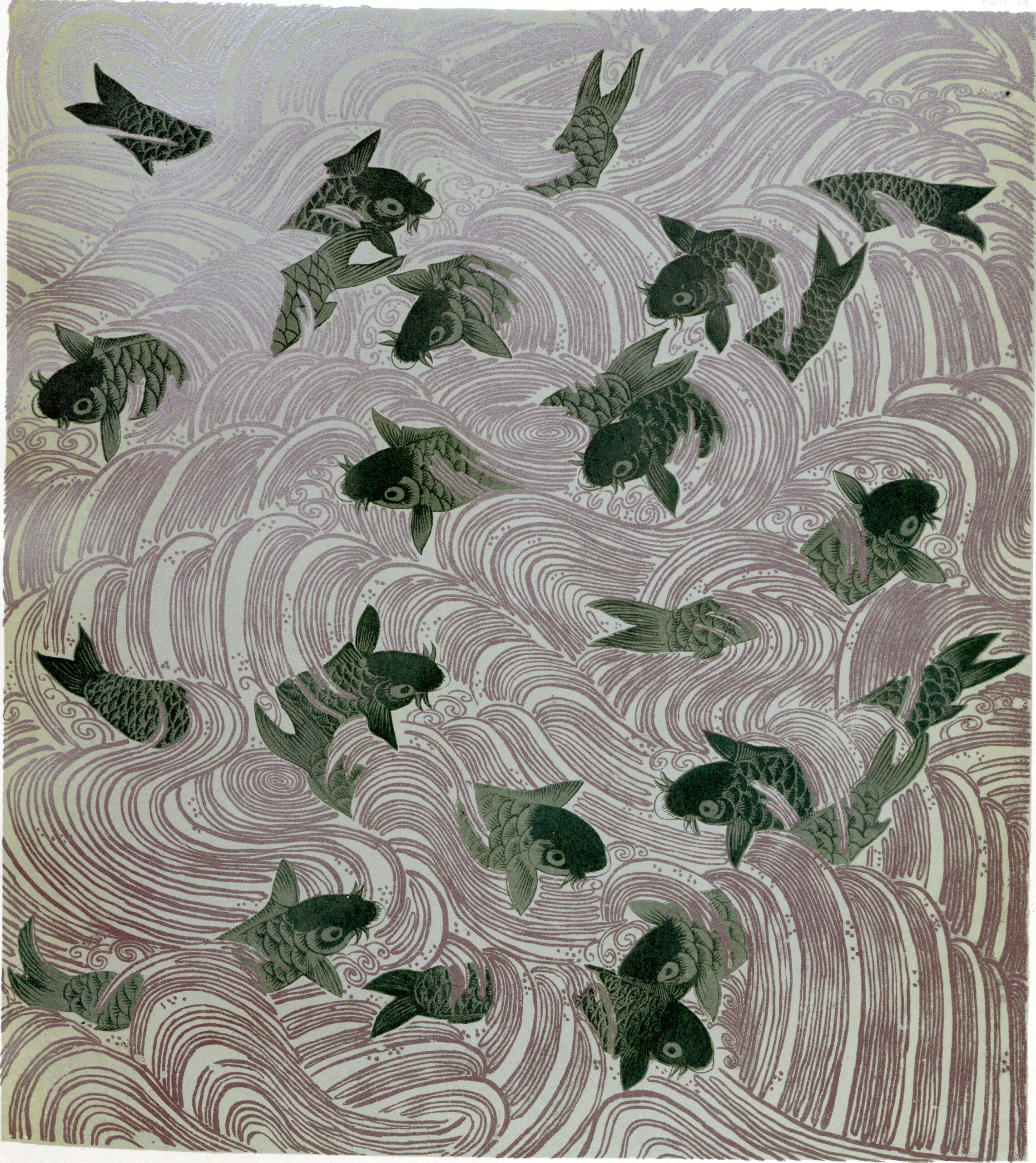

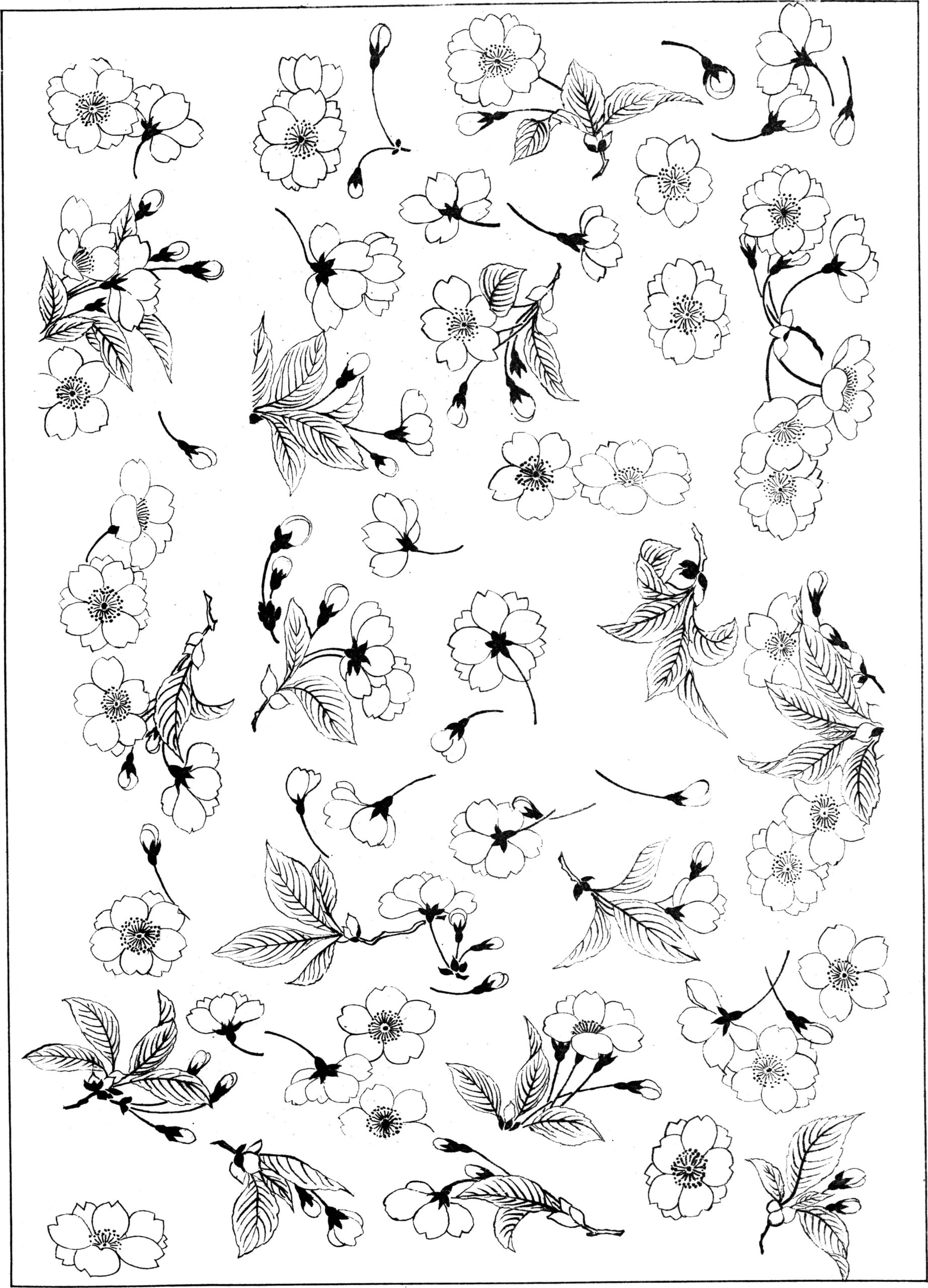

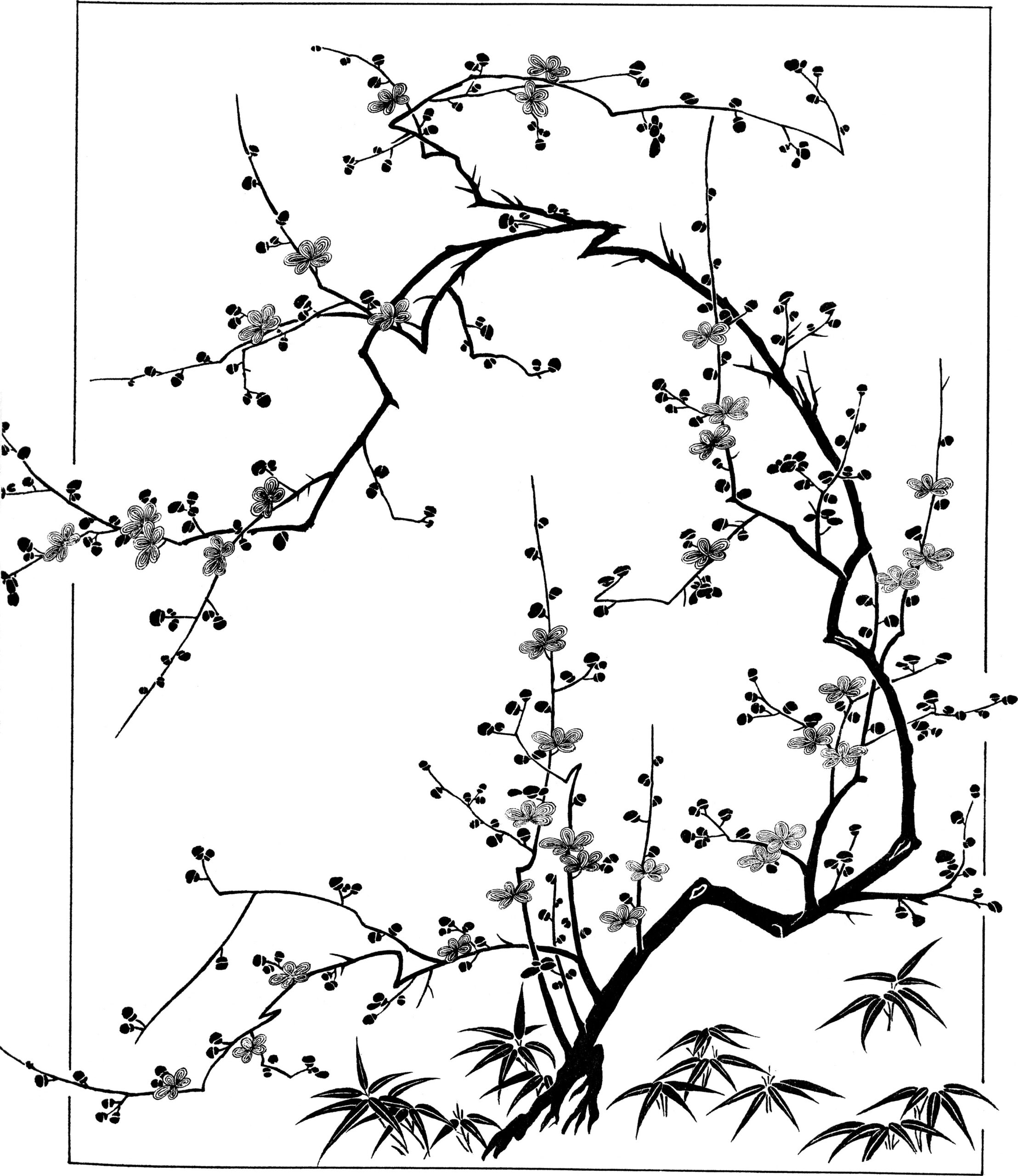

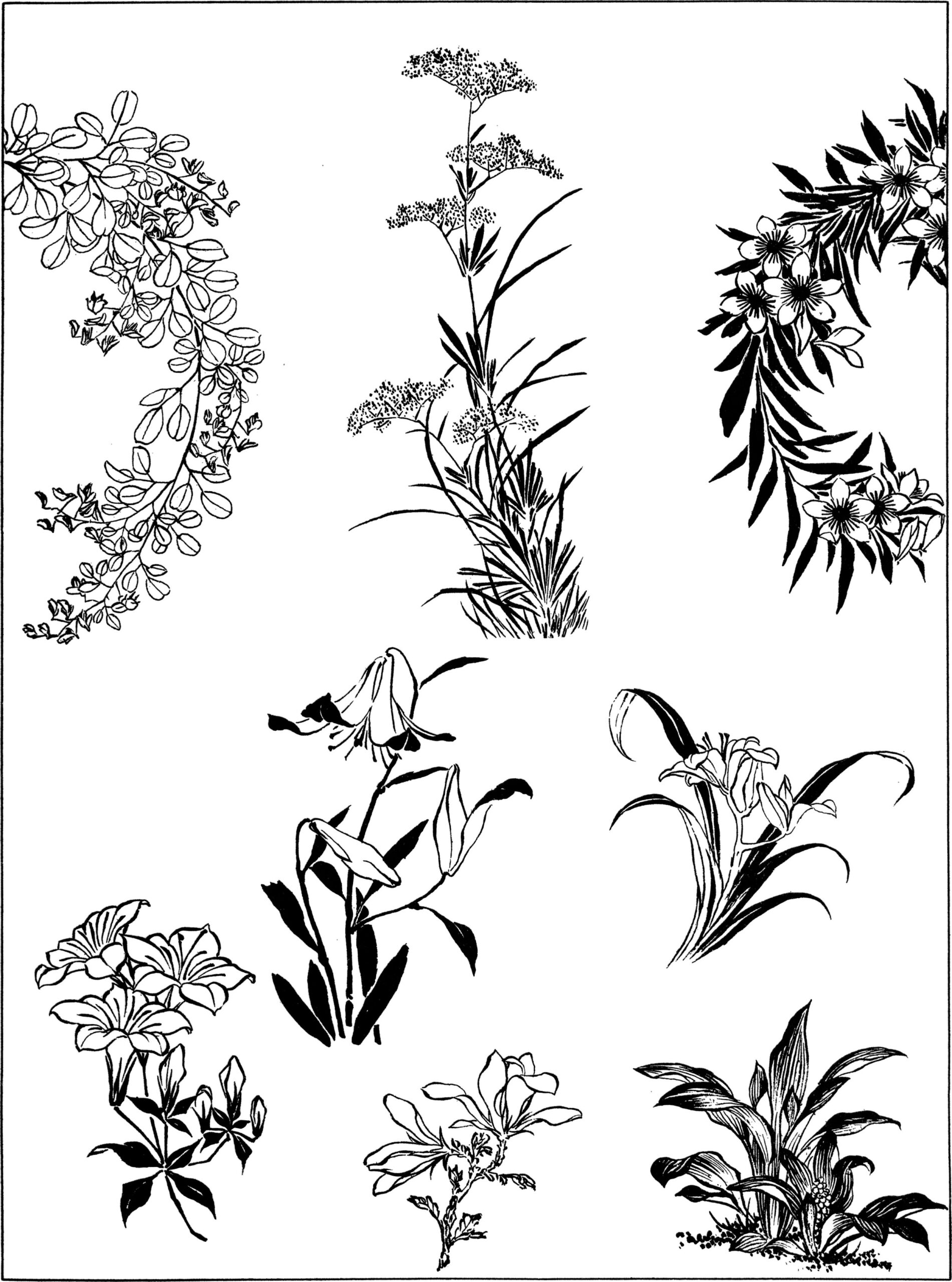

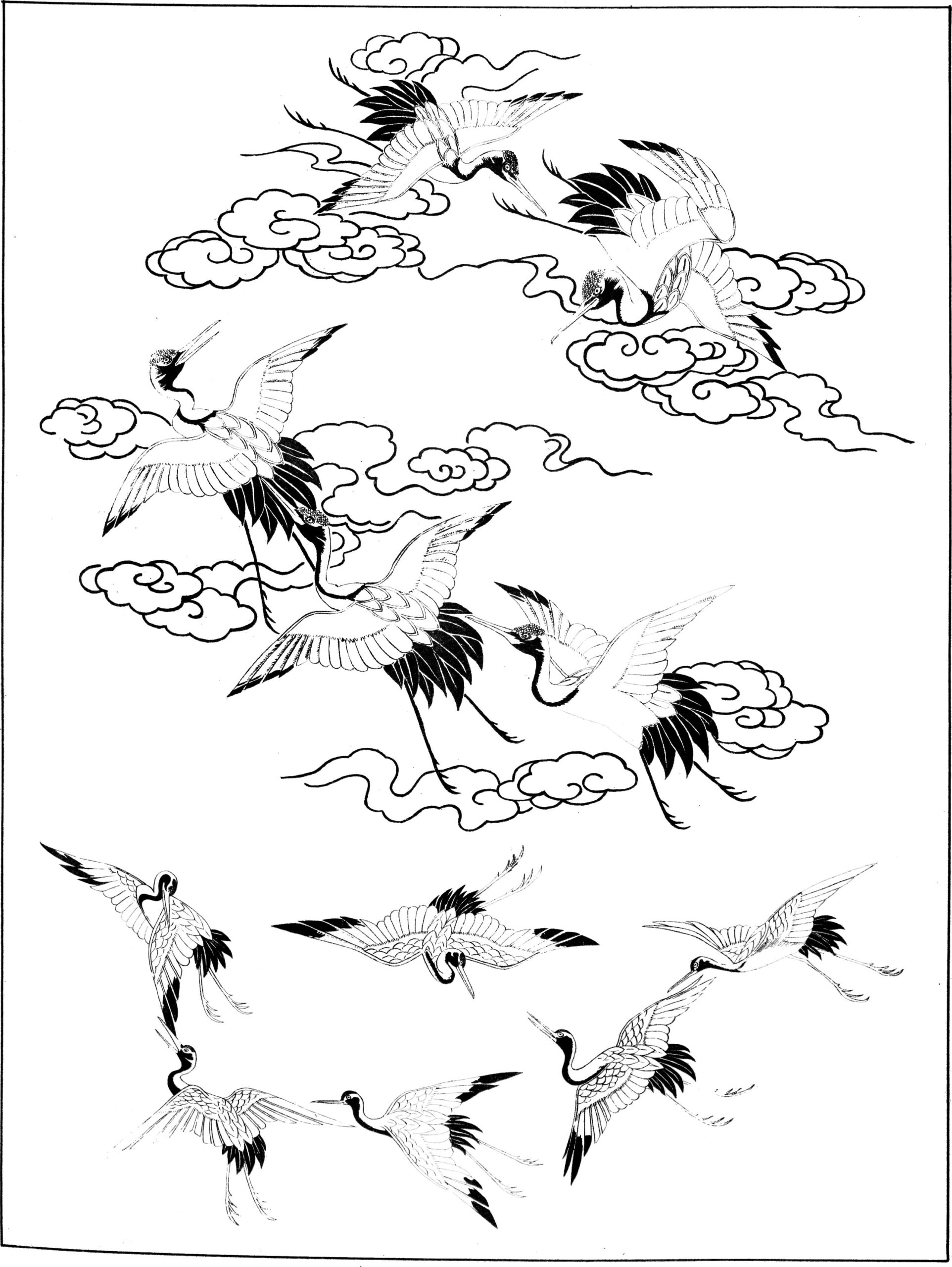

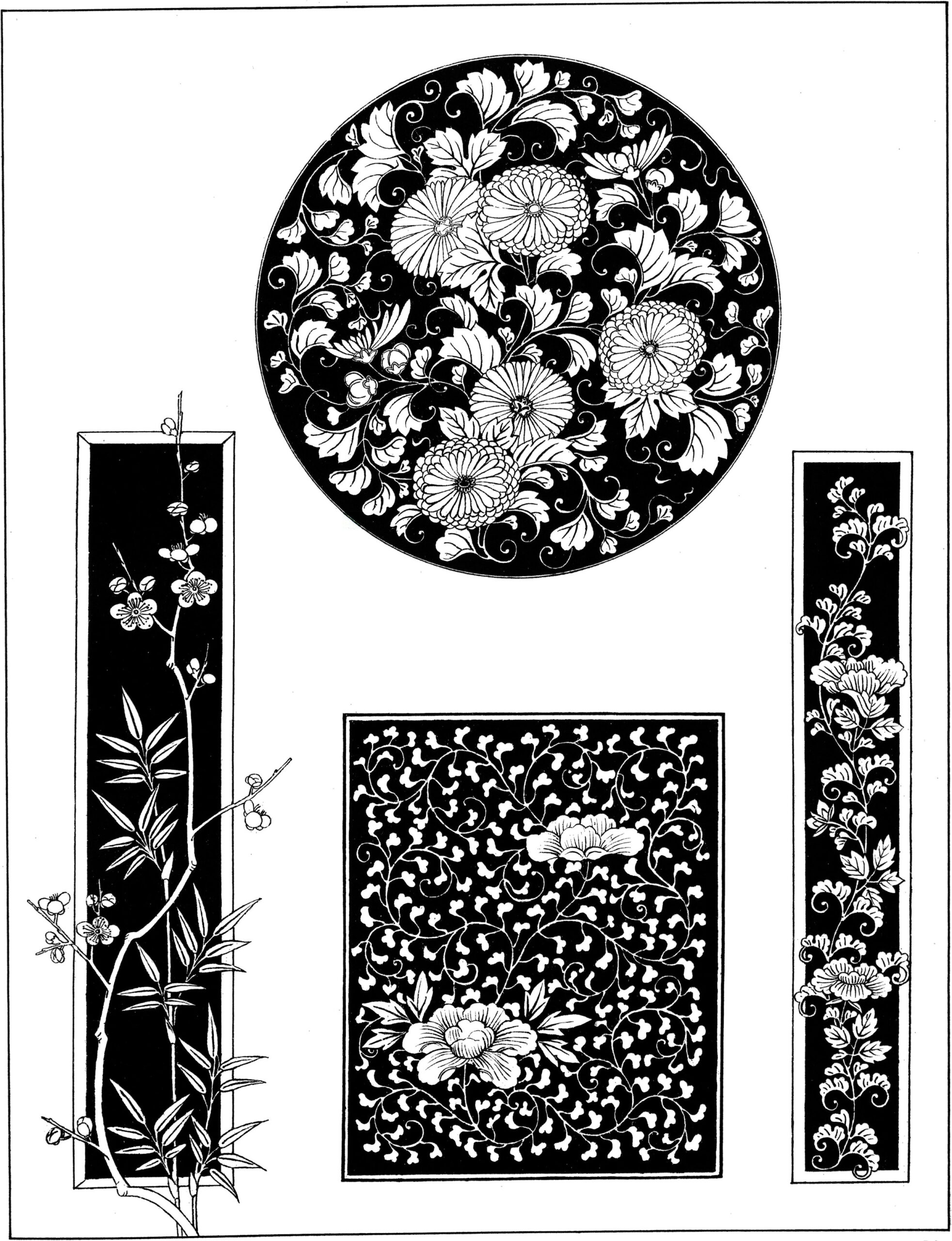

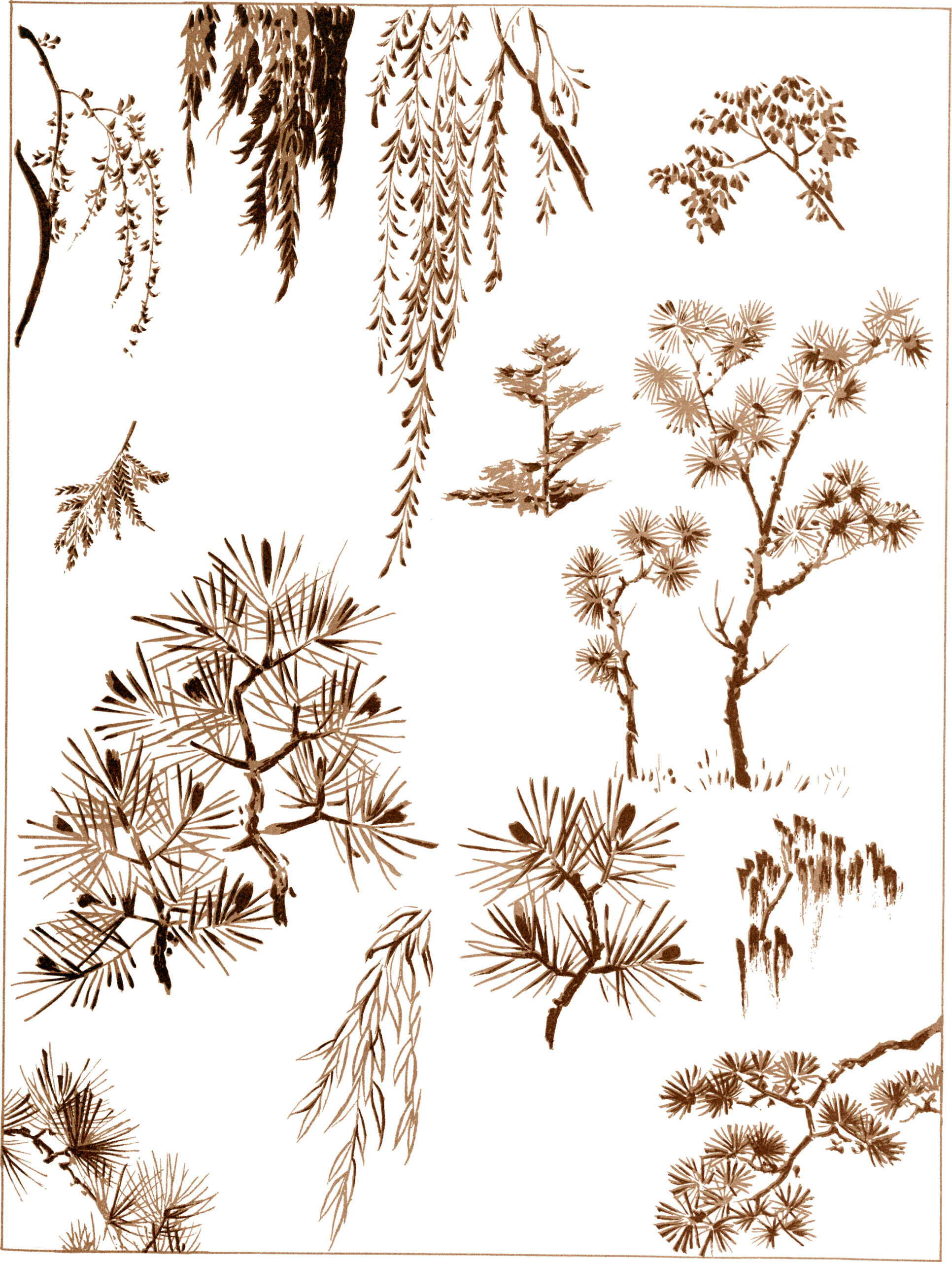

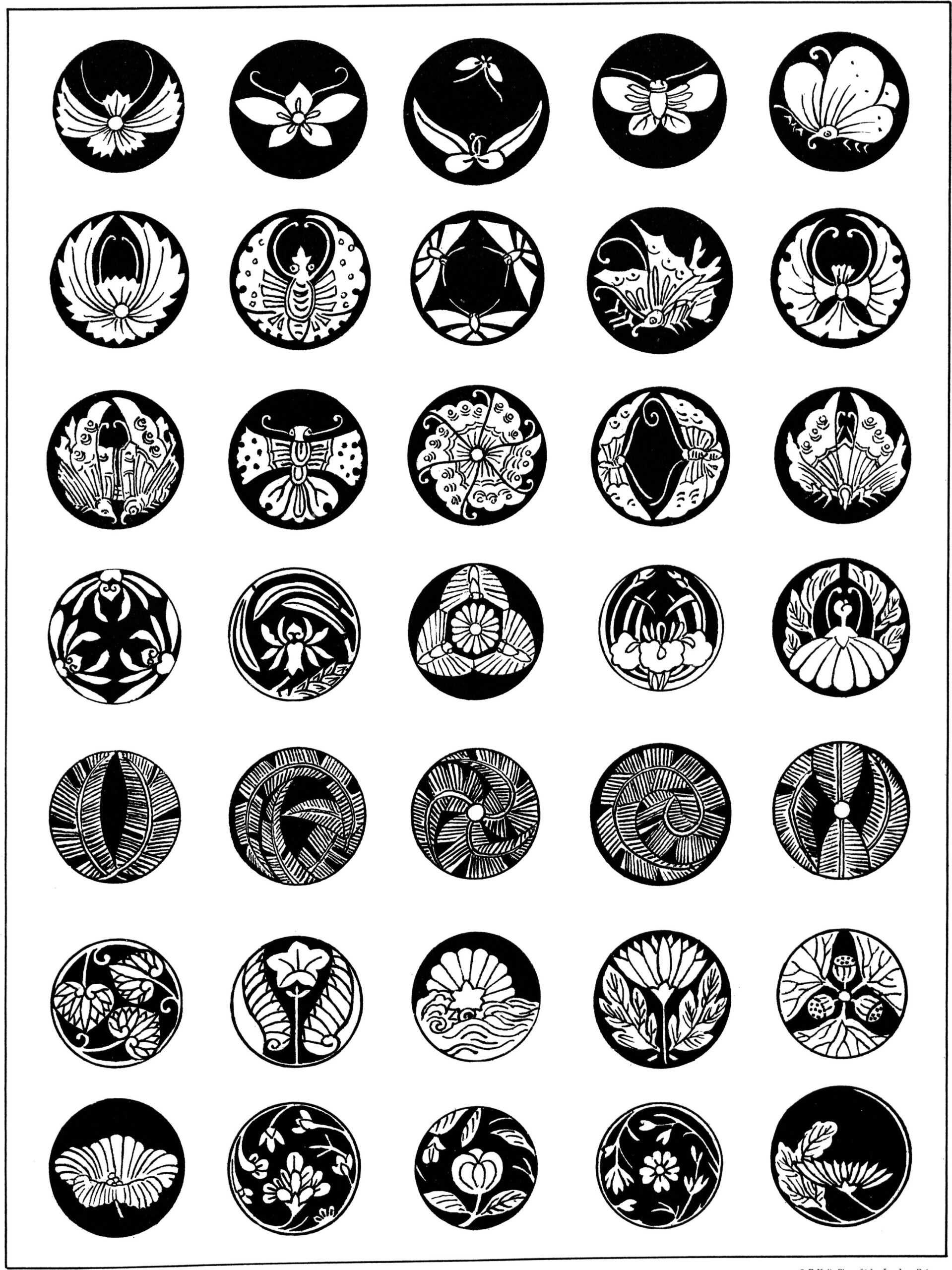

Cutler’s renderings of Japanese design motifs, undertaken in his free time, are the lasting legacy of his book, particularly for those on the prowl for copyright-free graphics.

Cutler observed that the “most characteristic” element of Japanese decoration was its close ties to the natural world, adding that unlike Western designers, a Japanese artist “would throw his design a little out of the center, and cleverly balance the composition by a butterfly, a leaf, or even a spot of color.”

The below plant studies are drawn from the work of the great ukiyo‑e master Hokusai, a “man of the people” who ushered in a period of “vitality and freshness” in Japanese art.

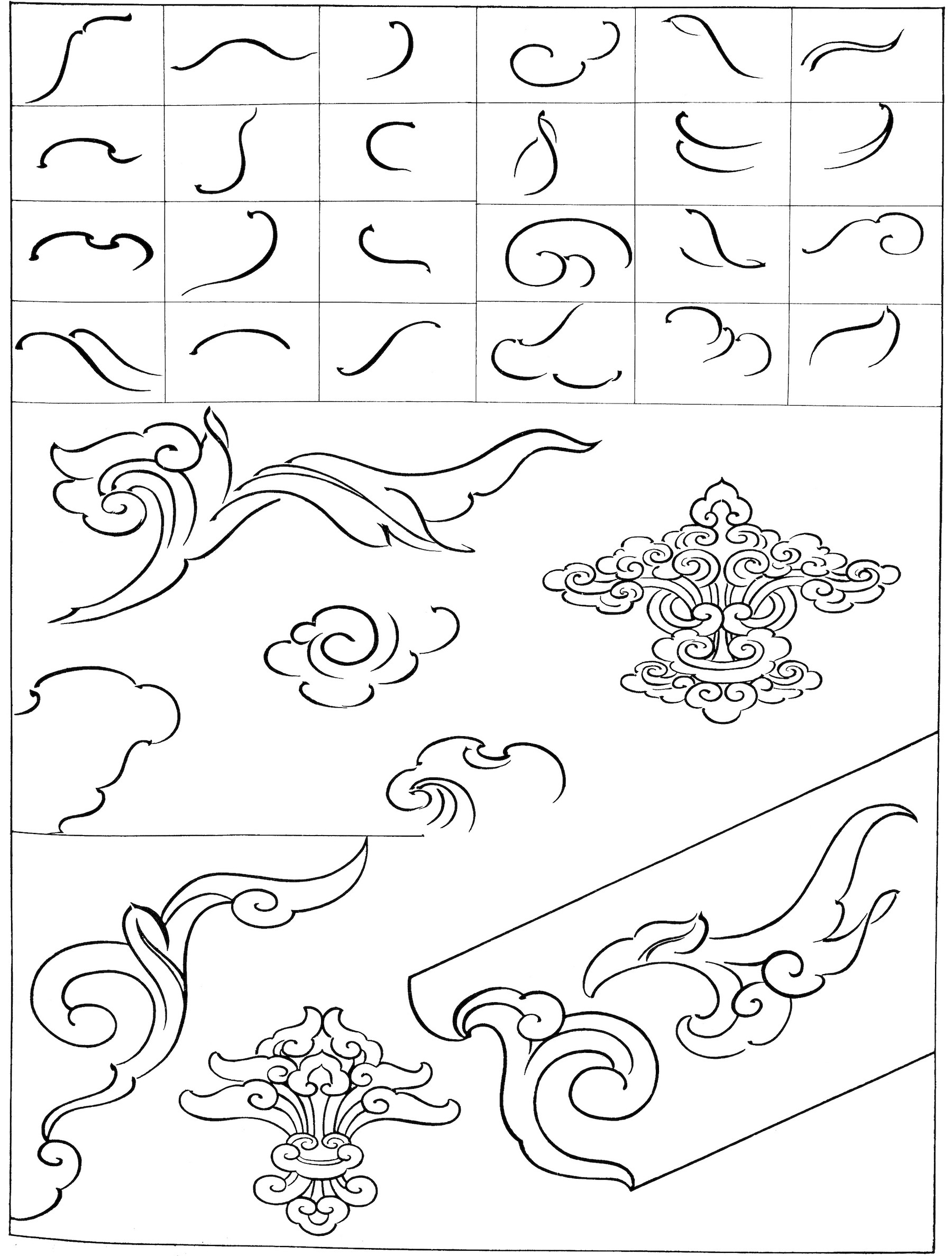

A sampler of curved lines made with single brush strokes can be used to create clouds or the intricate scrollwork that inspired Western artists and designers of the Aesthetic Movement.

While Cutler might not have thought much of Japanese architecture, it’s worth noting that his book shows up in the footnotes of Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan: The Role of Traditional Japanese Art and Architecture in the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Take a peek at some Japanese-inspired wallpaper of Cutler’s own design, then explore A Grammar of Japanese Ornament and Design by Thomas W. Cutler here.

Related Content

Download Classic Japanese Wave and Ripple Designs: A Go-to Guide for Japanese Artists from 1903

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.