Between 711 and 1492, much of the Iberian Peninsula, including modern-day Spain, was under Muslim rule. Not that it was easy to hold on to the place for that length of time: after the fall of Toledo in 1085, Al-Andalus, as the territory was called, continued to lose cities over the subsequent centuries. Córdoba and Seville were reconquered practically one right after the other, in 1236 and 1248, respectively, and you can see the invasion of the first city animated in the opening scene of the Primal Space video above. “All over the land, Muslim cities were being conquered and taken over by the Christians,” says the companion article at Primal Nebula. “But amidst all of this, one city remained unconquered, Granada.”

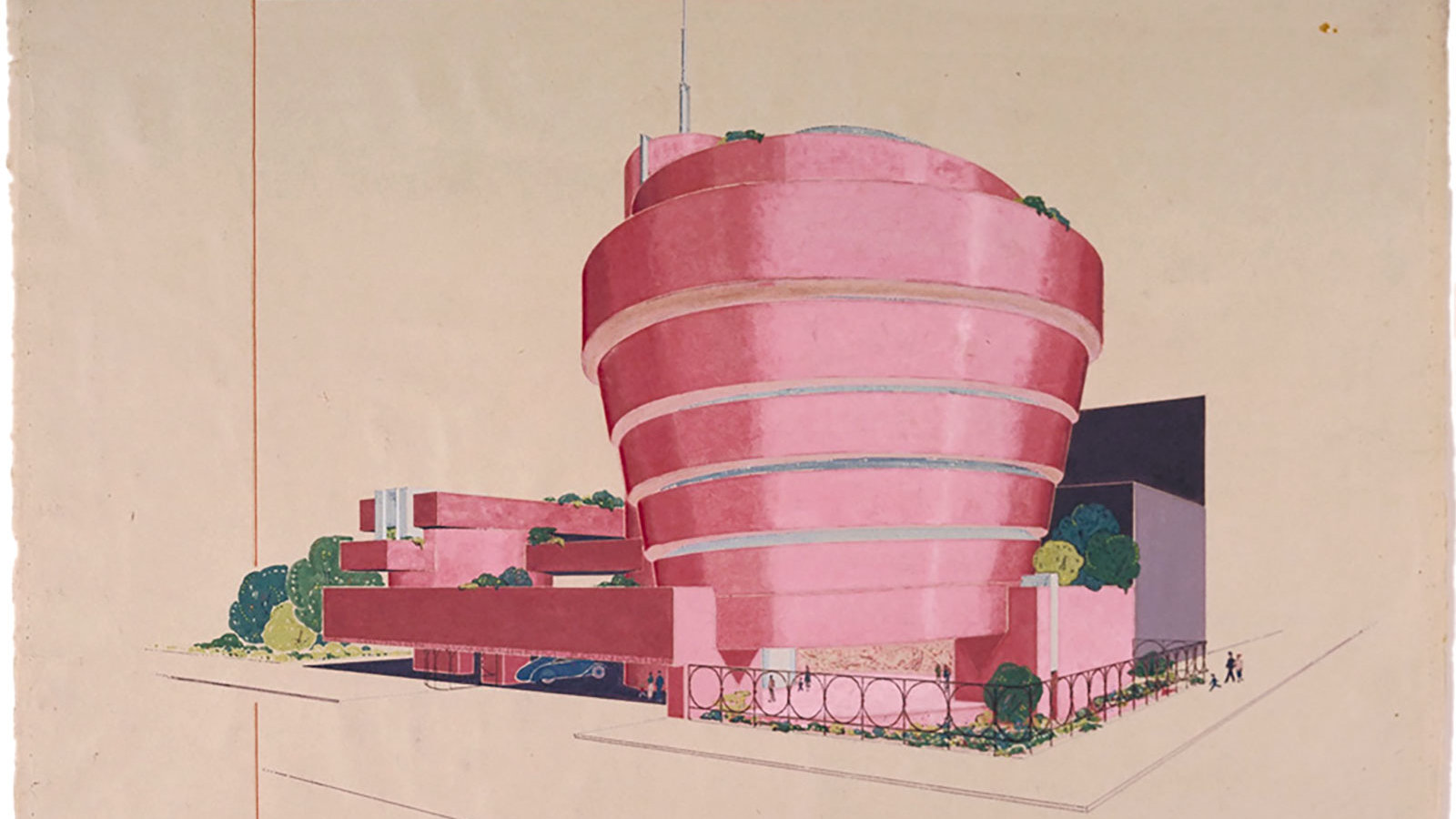

“Thanks to its strategic position and the enormous Alhambra Palace, the city was protected,” and there the Alhambra remains today. A “thirteenth-century palatial complex that’s one of the world’s most iconic examples of Moorish architecture,” writes BBC.com’s Esme Fox, it’s also a landmark feat of engineering, boasting “one of the most sophisticated hydraulic networks in the world, able to defy gravity and raise water from the river nearly a kilometer below.”

The jewel in the crown of these elaborate waterworks is a white marble fountain that “consists of a large dish held up by twelve white mythical lions. Each beast spurts water from its mouth, feeding four channels in the patio’s marble floor that represent the four rivers of paradise, and then running throughout the palace to cool the rooms.”

The fuente de los Leones also tells time: the number of lions currently indicates the hour. This works thanks to an ingenious design explained both verbally and visually in the video. Anyone visiting the Alhambra today can admire this and other examples of medieval opulence, but travelers with an engineer’s cast of mind will appreciate even more how the palace’s builders got the water there at all. “The hill was around 200 meters above Granada’s main river,” says the narrator, which entailed an ambitious project of damming and redirection, to say nothing of the pool above the palace designed to keep the whole hydraulic system pressurized. The Alhambra’s heated baths and well-irrigated gardens represent the luxurious height of Moorish civilization, but they also remind us that, then as now, beneath every luxury lies an impressive feat of technology.

Related content:

The Brilliant Engineering That Made Venice: How a City Was Built on Water

How Toilets Worked in Ancient Rome and Medieval England

The Amazing Engineering of Roman Baths

Historic Spain in Time Lapse Film

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.