Guy de Maupassant ate lunch at the restaurant in the base of the Eiffel Tower nearly every day, that being the only place in Paris where he wouldn’t have to look at the Eiffel Tower. 130 years later, the observation deck of the Tour Montparnasse is known to offer the most beautiful vista on the French capital — thanks precisely to the invisibility of the Tour Montparnasse. Spare a thought, if you will, for that highly conspicuous building, quite possibly the loneliest in Europe. Since its completion in 1973, it has stood as the sole skyscraper in Paris proper, its famous unsightliness having inspired a ban on the construction of buildings over seven stories high in the city center.

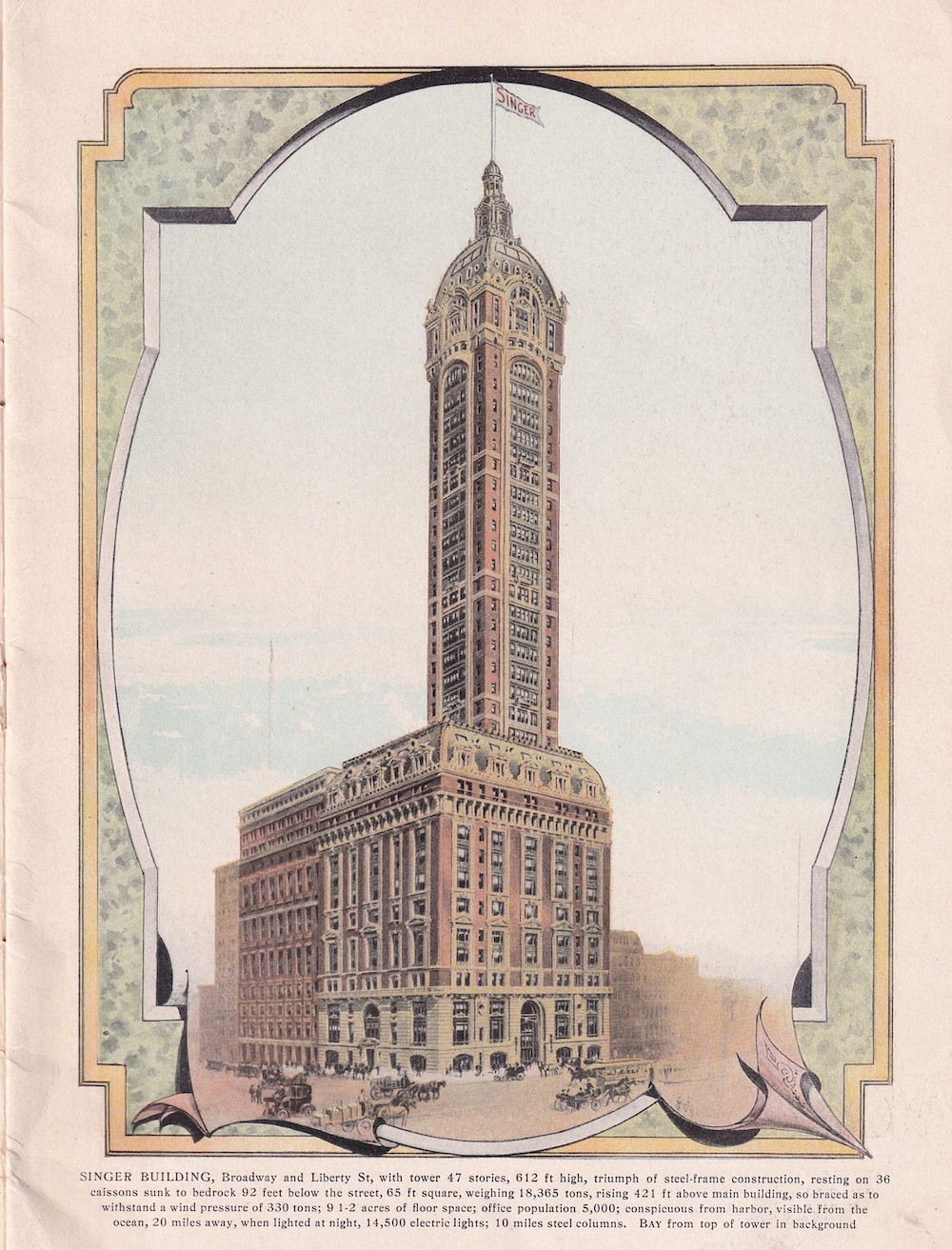

Paris isn’t alone in its lack of skyscrapers, a condition travelers from Asia and America notice in cities all over the Continent. In the video above, construction-themed Youtube channel The B1M explores the reasons for this relative paucity of tall towers in the capitals of Europe. “When skyscrapers first rose to prominence in the 19th century, first in Chicago and later in New York, many European cities were already firmly established with grand historic buildings and public spaces that left little room for large new structures,” says its narrator. At that time, a growing sense of cultural competition between America and Europe also meant that “each continent became wary of adopting the other’s concepts.”

Then came the Second World War, in the wake of whose devastation of Europe “an overwhelming desire to restore what had been destroyed took hold.” Few Continental cities held off the kind of demand for floor space that drove skyscraper construction in America. In the east, the Soviets built mostly “mid-rise, repetitive structures that sought to rehouse much of the population”; in the west, the restrictive phenomenon of “Brusselization” took hold in response to a wave of bulky postwar-modernist structures “that had little regard for architectural or cultural value.” This led to “a general dislike for modern buildings across Europe, with many seeing them as bland or soulless.”

No one who’s spent time in American city centers built up predominantly in the 1960s and 70s can dismiss those European detractors’ fears. But it would be a lie to claim that European cities have avoided skyscrapers entirely: even Paris has simply pushed them a few miles away, into unromantic business districts like La Défense. Ever-taller buildings have symbolized modernity for well over a century now, and no civilization can afford to keep modernity at too great a distance. Taking note of how attitudes toward skyscrapers have been “softening across the Continent” in the 21st century, this B1M video speculates on the possibility of a “skyscraper boom” in Europe. But even if that should happen, the Tour Montparnasse will surely continue standing alone.

Related Content:

Why Do People Hate Modern Architecture?: A Video Essay

The Creation & Restoration of Notre-Dame Cathedral, Animated

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.