Published in 1864, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground has a reputation as the first existentialist novel. It established a template for the genre with a portrait of an isolated man contemptuous of the sordid society around him, paralyzed by doubt, and obsessed with the pain and absurdity of his own existence. Also true to form, the narrative, though it has a plot of sorts, does not redeem its hero in any sense or offer any resolution to his gnawing inner conflict, concluding, literally, as an unfinished text. Thirteen years later, the great Russian writer, his health in decline but his literary reputation and financial prospects much improved, wrote a similar story, “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man.”

In this tale, an unnamed narrator also meditates on his absurd state, to the point of suicide. But he observes this spiritual malaise at a distance, recalling the story as an older man from a vantage point of wisdom: “I am a ridiculous person,” the story begins, “Now they call me a madman. That would be a promotion if it were not that I remain as ridiculous in their eyes as before. But now I do not resent it, they are all dear to me now.” This character, unlike Dostoevsky’s bitter underground man, has had a transformative experience—a dream in which he experiences the full moral weight of his choices on a grand scale. In a moment of instant enlightenment, our protagonist becomes a kinder, more humane person concerned with the welfare of others.

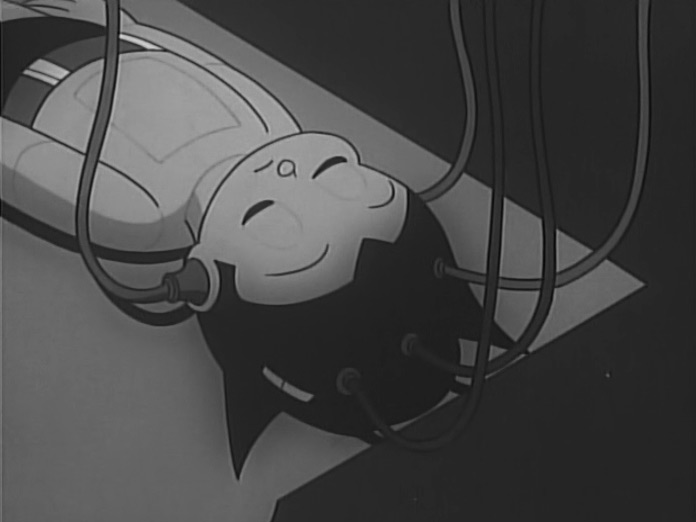

It is the difference between these two tales which makes the static, internal Underground a very difficult story to adapt to the screen—as far as I know it hasn’t been done—and “Ridiculous Man,” with its vivid dream imagery and dynamic characterization, almost ideal. The 1992 animation (in two parts above) uses painstakingly hand-painted cells to bring to life the alternate world the narrator finds himself navigating in his dream. From the flickering lamps against the dreary, darkened cityscape of the ridiculous man’s waking life to the shifting, sunlit sands of the dreamworld, each detail of the story is finely rendered with meticulous care. Drawn and directed by Russian animator Alexander Petrov—who won an Academy Award for his 1999 adaptation of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea—this is clearly a labor of love, and of tremendous skill and patience.

The technique Petrov uses, writes Galina Saubanova, is one of“Finger Painting”: “Forcing the paint on the glass, the artist draws with his fingers, using brushes only in exceptional cases. One figure is one film frame, which flashes within 1/24 of a second while watching. Petrov draws more than a thousand paintings for one minute of his film.” In Russian with English subtitles taken from Constance Garnett’s translation, the twenty-minute “animated painting” sublimely realizes Dostoevsky’s tale of personal transformation with a lightness and lyricism that a live-action film cannot duplicate, although a 1990 BBC production called “The Dream” certainly has much to recommend it. If you like Petrov’s work, be sure to watch his Old Man and the Sea here. Also online are his short films “The Mermaid” (1997) and “My Love” (2006).

Related Content:

See a Beautifully Hand-Painted Animation of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (1999)

Watch Piotr Dumala’s Wonderful Animations of Literary Works by Kafka and Dostoevsky

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness