Humorist James Thurber never tired of subjecting puny male milquetoasts to powerful female bullies.

In his view, members of the fairer sex were never femme fatales or fussy matrons, but rather battle-loving warriors in simple Wilma Flintstone-esque frocks. They are immune to the traditionally feminine concerns of the period—hair, children, the living room drapes… they get their pleasure dominating Walter Mitty and his ilk.

(Was he terrified of Woman? Resentful of her? The story he stuck to was that he’d conceived of his comic portrayal for the sole purpose of “egging her on.”)

There is one memorable instance where the little guy was allowed to come out on top. “The Unicorn in the Garden” is a story first published in The New Yorker on October 31, 1939. No spoilers, but there’s a close resemblance to Harvey, Mary Chase’s much-produced play about a mild-mannered gent whose devotion to a 6’ tall invisible rabbit drives his domineering sister around the bend.

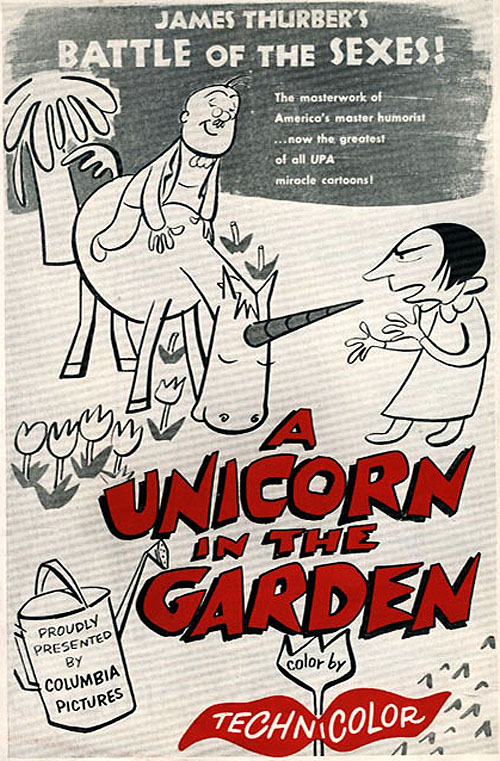

The 1953 cartoon adaptation above brought Thurber’s drawings to life, whilst preserving the dialogue of the original in its entirety. The original story was published with only a single illustration, but director William T. Hurtz’s had hundreds of New Yorker cartoons to draw upon. Legend has it that Hurtz purposefully assigned some of United Productions of America’s least gifted animators to the project, hoping to duplicate Thurber’s ”nice, lumpy look.” The plan was for “The Unicorn in the Garden” to be part of a full-length Thurber feature, but alas, the studio pulled the plug on Men, Women and Dogs before it could be completed. Moral: Don’t count your boobies until they are hatched.

“A Unicorn in the Garden” was later voted #48 of the 50 Greatest Cartoons of all time by members of the animation field. You can find more literary animations in our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Eudora Welty Writes a Quirky Letter Applying for a Job at The New Yorker (1933)

New Yorker Cartoon Editor Bob Mankoff Reveals the Secret of a Successful New Yorker Cartoon

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday