I think, as social primates, we want to feel a strong sense of belonging either in a relationship or to a community—or both. But also intrinsic to our humanity is a feeling that we are truly alone.

—Filmmaker Andrea Dorfman, 2010

When they first became friends, poet Tanya Davis and filmmaker Andrea Dorfman talked a lot about the pleasures and hardships of being alone. Davis had just gone through a break up, and Dorfman was just embarking on a relationship after four years of flying solo.

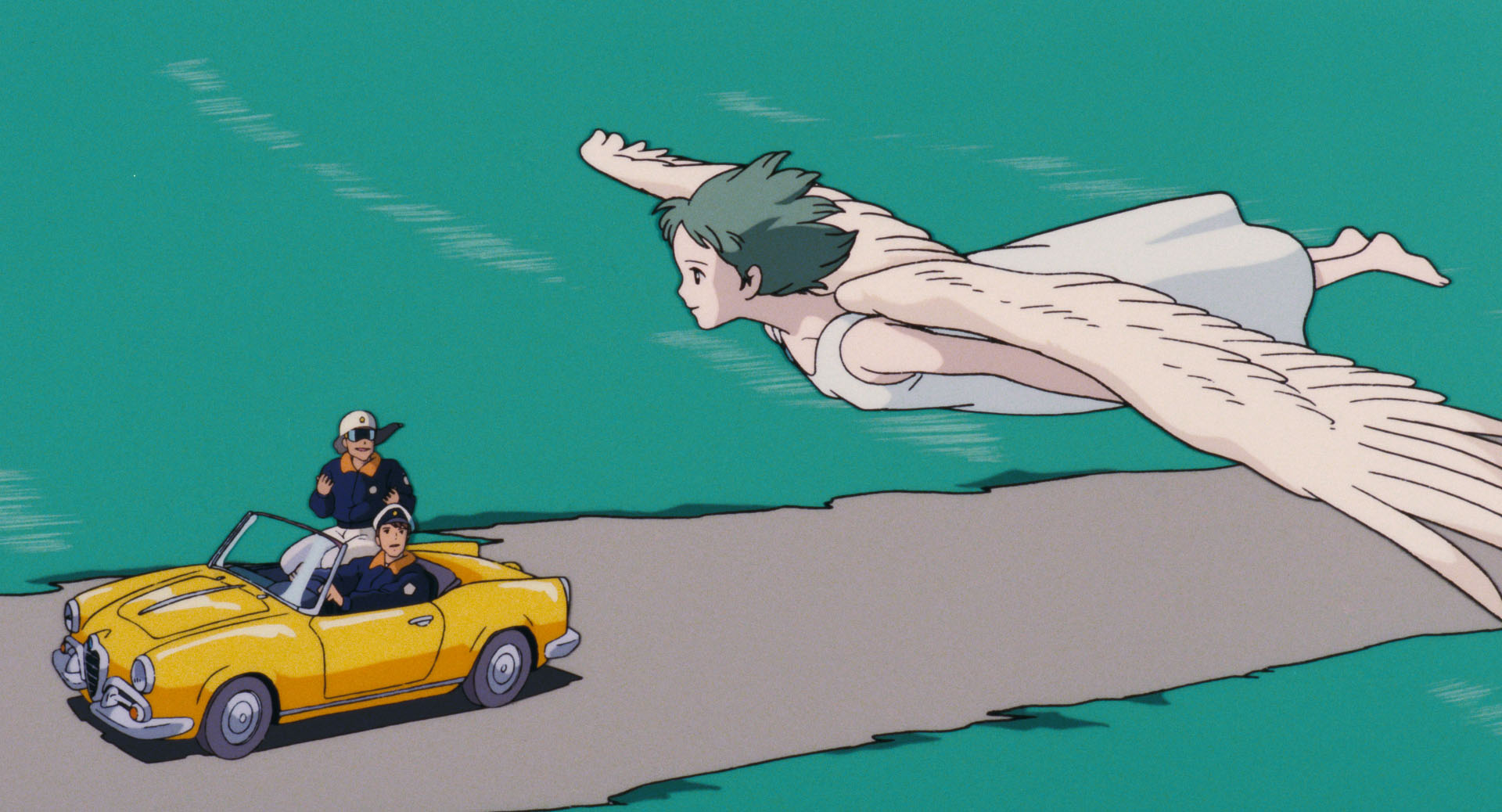

These conversations led to a collaboration, 2010’s How to Be At Alone (see below), a whimsical videopoem that combines live action and animation to consider some of solitude’s sweeter aspects, like sitting on a bench as signal to the universe that one is available for impromptu conversation with a stranger.

That bench reappears in their 2020 follow up, How to Be At Home, above. Now it is cordoned off with black and yellow caution tape, a familiar public health measure in 2020.

As with the earlier project, a large part of Davis’ purpose was to reflect and reassure, both herself, and by extension, others.

Although she has become a poster child for the joys of solitude, she also relishes human contact, and found herself missing it terribly while sheltering alone in the early days of the pandemic. Writing the new poem gave her “an anchor” and a place to put her anxiety.

Dorfman notes that the project, which was commissioned by the National Film Board of Canada as part of a short film collection about Canadians navigating life during the pandemic, was “essentially catalyzed by COVID.”

As she embarked on the project, she wondered if the pandemic would be over by the time it was complete. As she told the CBC’s Tom Power:

There was this feeling that this could go away in a month, so this better be finished soon, so it’s still relevant. So as an artist, as a filmmaker, I thought, “I have to crank this out” but there’s no fast and easy way to do animation. It just takes so long and as I got into it and realized that this was going to be a marathon, not a sprint, the images just kept coming to me and I really just made it up as I went along. I’d go into my studio every day not knowing what lay ahead and I’d think, “Okay, so, what do we have up next? What’s the next line? And I’d spend maybe a week on a line of the poem, animating it.

It appears to have been an effective approach.

Dorfman’s painted images ripple across the fast turning pages of an old book. The titles change from time to time, and the choices seem deliberate—The Lone Star Ranger, Le Secret du Manoir Hanté, a chapter in The Broken Halo—“Rosemary for Remembrance.”

“It’s almost as though the way the poem is written there are many chapters in the book. (Davis) moves from one subject to another so completely,” Dorfman told the University of King’s College student paper, The Signal.

In the new work, the absence of other people proves a much heavier burden than it does in How To Be Alone.

Davis flirts with many of the first poem’s settings, places where a lone individual might have gone to put themselves in proximity to other humans as recently as February 2020:

Public transportation

The gym

A dance club

A description from 2010:

The lunch counter, where you will be surrounded by chow-downers, employees who only have an hour and their spouses work across town, and they, like you, will be alone.

Resist the urge to hang out with your cell phone.

In 2020, she struggles to recreate that experience at home, her phone serving as her most vital link to the outside world, as she scrolls past images of a Black Lives Matter protests and a masked essential worker:

I miss lunch counters so much I’ve been eating [pickles and] toasted sandwiches while hanging unabashedly with my phone.

See How to Be at Home and the 29 other films that comprise The Curve, the National Film Board of Canada series about life in the era of COVID-19 here.

How to be at Home

By Tanya Davis

If you are, at first, really fucking anxious, just wait. It’ll get worse, and then you’ll get the hang of it. Maybe.

Start with the reasonable feelings – discomfort, lack of focus, the sadness of alone

you can try to do yoga

you can shut off the radio when it gets to you

you can message your family or your friends or your colleagues, you’re not supposed to leave your home anyway, so it’s safe for you

There’s also the gym

you can’t go there but you could pretend to

you could bendy by yourself in your bedroom

And there’s public transportation

probably best to avoid it

but there’s prayer and meditation, yes always

employ it

if you have pains in your chest ‘cause your anxiety won’t rest

take a moment, take a breath

Start simple

things you can handle based on your interests

your issues and your triggers

and your inner logistics

I miss lunch counters so much I’ve been eating [pickles and] toasted sandwiches while hanging unabashedly with my phone

When you are tired, again of still being alone

make yourself a dinner

but don’t invite anybody over

put something green in it, or maybe orange

chips are fine sometimes but they won’t keep you charged

feed your heart

if people are your nourishment, I get you

feel the feelings that undo you while you have to keep apart

Watch a movie, in the dark

and pretend someone is with you

watch all of the credits

because you have time, and not much else to do

or watch all of the credits to remember

how many people come together

just to tell a story

just to make a picture move

And then, set yourself up dancing

like it’s a club where everyone knows you

and they’re all gonna hold you

all night long

they’re gonna dance around you and with you and on their own

it’s your favourite song

with the hardest bass and the cathartic drums

your heart pumps along/hard, you belong

you put your hands up to feel it

With the come down comes the weeping

those downcast eyes and feelings

the truth is you can’t go dancing, not right now

not at any club or party in any town

The heartbreak of this astounds you

it joins old aches way down in you

you can visit them, but please don’t stay there

Go outside if you’re able, breathe the air

there are trees for hugging

don’t be embarrassed

it’s your friend, it’s your mother, it’s your new crush

lay your cheek against the bark, it’s a living thing to touch

Sadly, leave all benches empty

appreciate the kindness in the distance of strangers

as you pine for company and wave at your neighbours

savour the depths of your conversations

the layers uncovered

in this strange space and time

Society is afraid of change

and no one wants to die

not now, from a tiny virus

not later from the world on fire

But death is a truth we all hate to know

we all get to live, and then we all have to go

In the meantime, we’re surrounded, we’re alone

each a thread woven in the fabric, unravelling in moments though

each a solo entity spinning on its axis, forgetting that the galaxy includes us all

Herein our fall

from grace from each other from god whatever, doesn’t matter

the disaster is that we believe we’re separate

we’re not

As evidenced by viruses taking down societies

as proven by the loneliness inherent in no gatherings

as palpable as the vacancy in the space of one person hugging

If this disruption undoes you

if the absence of people unravels you

if touch was the tether that held you together

and now that it’s severed you’re fragile too

lean into loneliness and know you’re not alone in it

lean into loneliness like it is holding you

like it is a generous representative of a glaring truth

oh, we are connected

we forget this, yet we always knew.

How to Be at Home will be added to the Animation section of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Watch 66 Oscar-Nominated-and-Award-Winning Animated Shorts Online, Courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada

Watch “Ryan,” Winner of an Oscar and 60 Other Awards

2020: An Isolation Odyssey–A Short Film Reenacts the Finale of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, with a COVID-19 Twist

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.