Leonard Cohen, High Priest Of Pathos…

Lord Byron of Rock and Roll…

Gentleman Zen

Master Of Misery…Morbidity… Erotic Despair…

Prince of Pessimism…Pain…

Troubadour For Troubled Souls…

The gravel-voiced singer-songwriter accumulated hundreds of nicknames over a career spanning more than half a century. He wasn’t thrilled by some of them, remarking to the BBC, “You get tired, over the years, hearing that you’re the champion of gloom.”

Taken all together, however, they make for a decent composite portrait of a prolific artist whose sensuality, mordant wit, and obsession with love, loss, and redemption never wavered.

He took some hiatuses, including a 5‑year stint as a monk in California’s Mount Baldy monastery, but never retired.

His final studio album, You Want It Darker, was released mere weeks before his death.

Journalist Rob Sheffield articulated the Cohen mystique in a Rolling Stone eulogy:

This man was both the crack in everything and the light that gets in. Nobody wrote such magnificently bleak ballads for brooding alone in the dark, staring at a window or wall – “Joan of Arc,” “Chelsea Hotel,” “Tower of Song,” “Famous Blue Raincoat,” “Closing Time.” He was music’s top Jewish Canadian ladies’ man before Drake was born, running for the money and the flesh. Like Bowie and Prince, he tapped into his own realm of spiritual and sexual gnosis, and like them, he went out at the peak of his musical powers. No songwriter ever adapted to old age with more cunning or gusto.

Cohen also excelled at interviews, leaving behind a wealth of generous, freewheeling recordings, at least three of which have become fodder for animators.

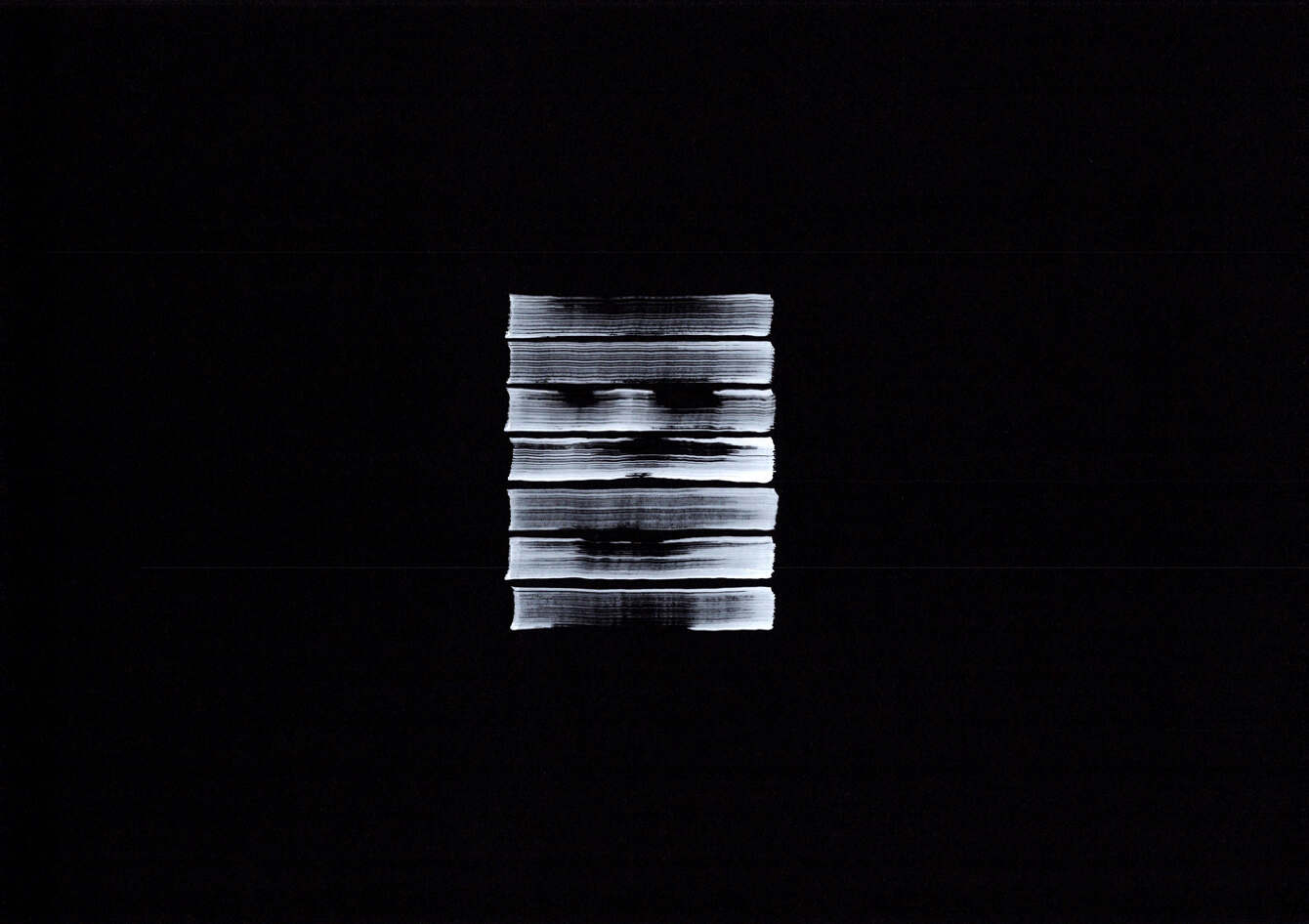

The animation at the top of the page is drawn from Cohen’s 1966 interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Adrienne Clarkson, shortly after the release of his experimental novel, Beautiful Losers. (His debut album was still a year and a half away.)

Earlier in the interview, Cohen mentions the “happy revolution” he encountered in Toronto after an extended period on the Greek island of Hydra:

I was walking on Yorkville Street and it was jammed with beautiful, beautiful people last night. I thought maybe it could spread to the [other] streets and maybe even … where’s the money district? Bay Street?… I thought maybe they could take that over soon, too.

How to tap into the source of all this happiness?

The future Zen monk Cohen was pretty convinced it could be located by sitting quietly, though he doesn’t condemn those using drugs or alcohol as an assist, explaining that his fellow Canadian, abstract expressionist Harold Town, “gets beautiful under alcohol. I get stupid and generally throw up.”

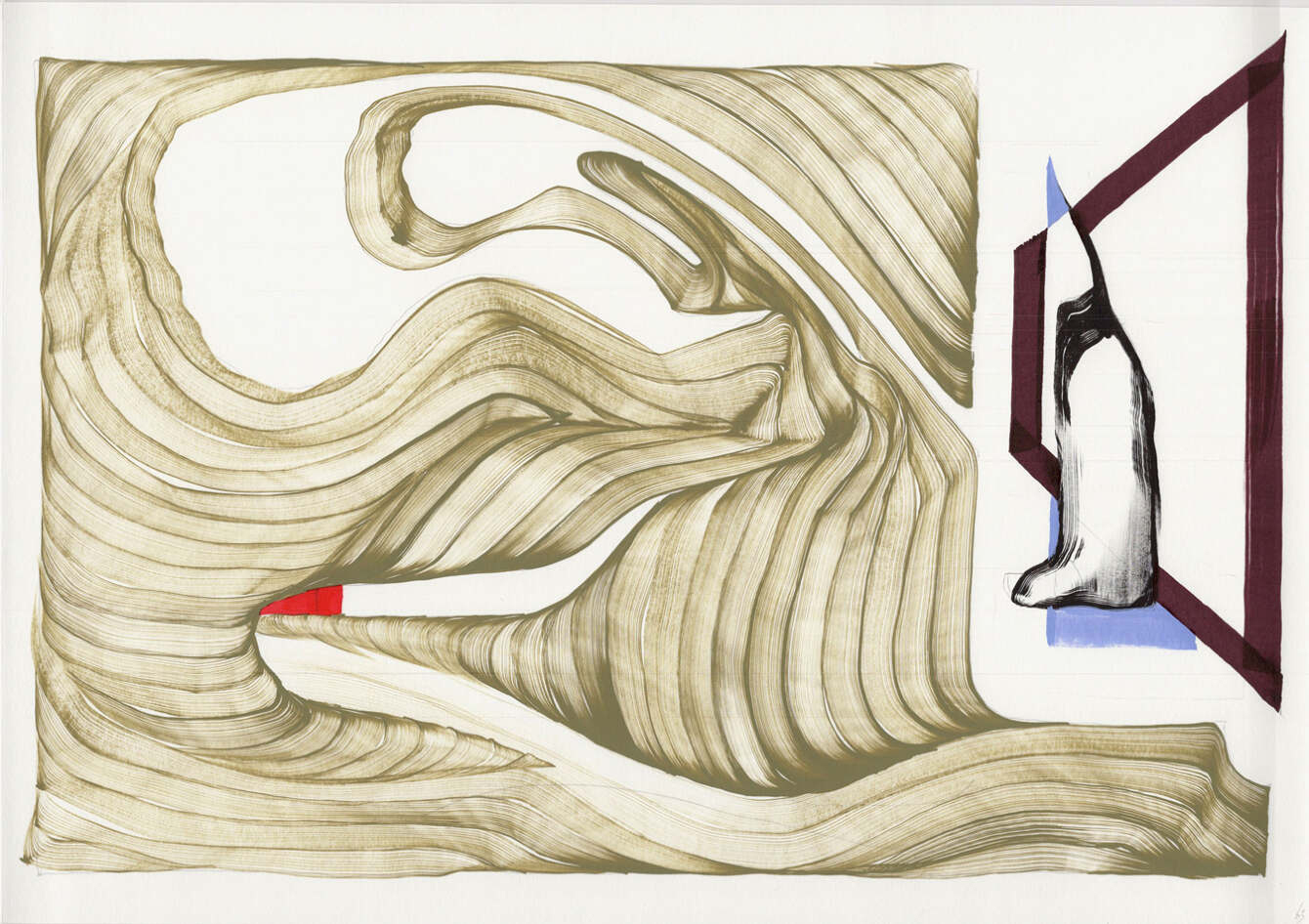

8 years later, WBAI’s Kathleen Kendel came armed with a poem for Cohen to read on air, and also plumbed him as to the origins of “Sisters of Mercy,” one of his best known songs, and the only one that didn’t require him to “sweat over every word.” (Possibly the consolation prize for his dashed hopes of erotic adventure with the song’s protagonists.)

(The animation here is by Patrick Smith for PBS’ Blank on Blank series.)

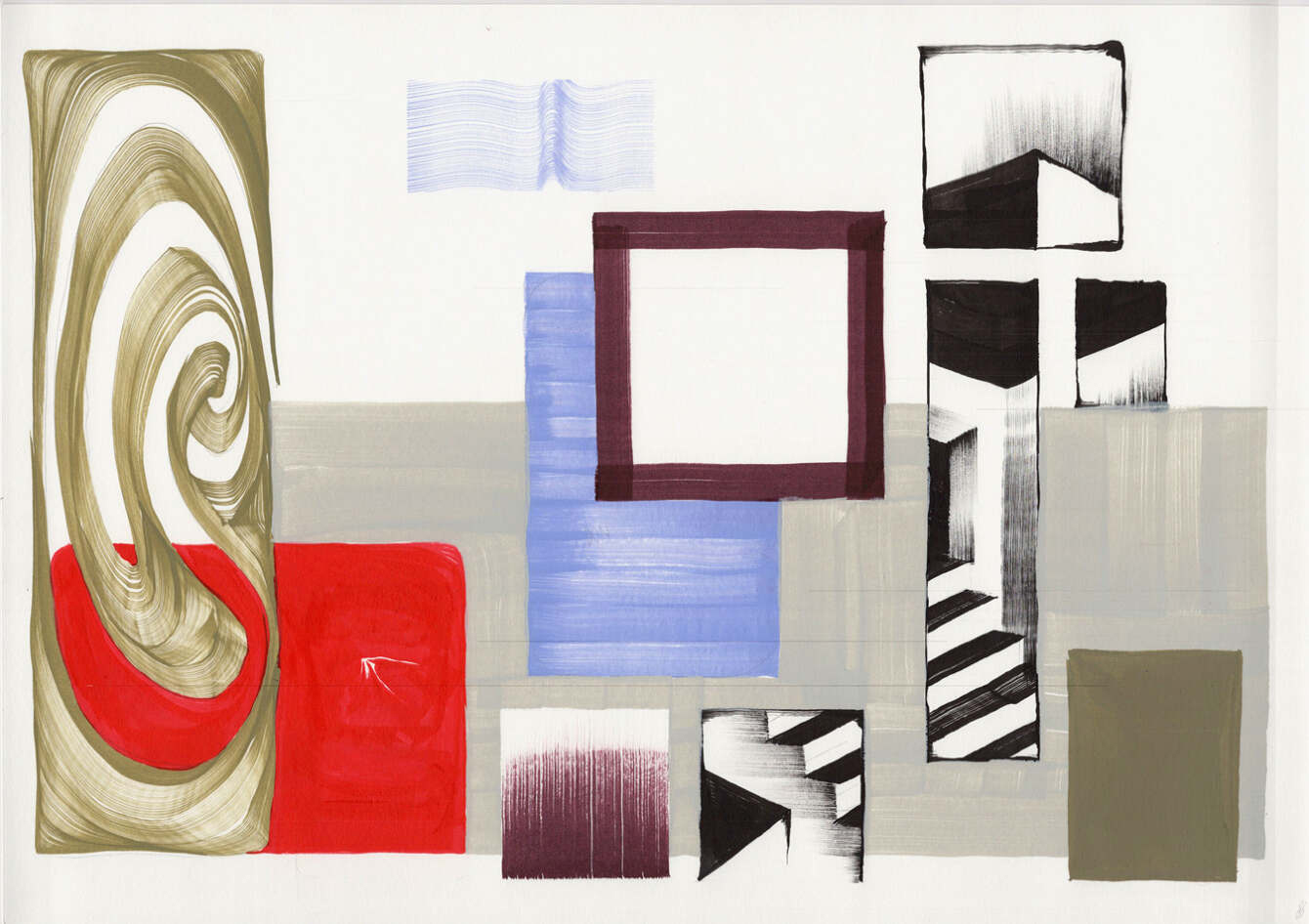

Animator Joe Donaldson riffs on an excerpt from Cohen’s final major interview, with The New Yorker’s editor-in-chief, David Remnick, above.

Remnick recalled that his subject, who died a few days later, was “in an ebullient mood for a man… who knew exactly where he was going, and he was headed there in a hurry. And at the same time, he was incredibly gracious.”

The 82-year-old Cohen spoke enthusiastically if somewhat pessimistically about having a lot of new material to get through, “to put (his) house in order,” but also admitted, “sometimes I just need to lie down.”

Related Content:

Hear Leonard Cohen’s Final Interview: Recorded by David Remnick of The New Yorker

Ladies and Gentlemen… Mr. Leonard Cohen: The Poet-Musician Featured in a 1965 Documentary

Leonard Cohen Plays a Spellbinding Set at the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.