Since George Orwell published his landmark political fable 1984, each generation has found ample reason to make reference to the grim near-future envisioned by the novel. Whether Orwell had some prophetic vision or was simply a very astute reader of the institutions of his day—all still with us in mutated form—hardly matters. His book set the tone for the next 70-plus years of dystopian fiction and film.

Orwell’s own political activities—his stint as a colonial policeman or his denunciation of several colleagues and friends to British intelligence—may render him suspect in some quarters. But his nightmarish fictional projections of totalitarian rule strike a nerve with nearly everyone on the political spectrum because, like the speculative future Aldous Huxley created, no one wants to live in such a world. Or at least no one will admit it if they do.

Even the institutions most likely to thrive in Orwell’s vision have co-opted his work for their own purposes. The C.I.A. rewrote the animated film version of Animal Farm. And if you’re of a certain vintage, you’ll recall Apple’s appropriation of 1984 in Ridley Scott’s Super Bowl ad that very year for the Macintosh computer. But of course not every Orwell adaptation has been made in the service of political or commercial opportunism. Long before the Apple ad, and Michael Radford’s 1984 film version of Nineteen Eighty-Four, there was the 1949 radio drama above. Starring British great David Niven, with intermission commentary by author James Hilton, the show aired on the educational radio series NBC University Theater.

This radio drama, the “first audio production of the most challenging novel of 1949,” opens with a trigger warning, of sorts, that prepares us for a “disturbing broadcast.” To audiences just on the other side of the Nazi atrocities and the nuclear bombings of Japan, then dealing with the threat of Soviet Communism, Orwell’s dystopian fiction must have seemed dire and disturbing indeed.

Every adaptation of a literary work is unavoidably also an interpretation, bound by the ideas and ideologies of its time. The Niven broadcast shares the same historical concerns as Orwell’s novel. More recently, this 70-year-old audio has itself been co-opted by a podcast called “Great Speeches and Interviews,” which edited the broadcast together with a perplexing selection of popular songs and an interview between journalists Glenn Greenwald and Dylan Ratigan. Whatever we make of these developments, one thing seems certain. We won’t be done with Orwell’s 1984 for some time, and it won’t be done with us.

Related Content:

George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984

The Cover of George Orwell’s 1984 Becomes Less Censored with Wear & Tear

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Of course it is only right to decry those of the extreme political Right, right?

Is it best to leave the depredations of the extreme political Left left alone?

Or do rhetorical gambits grow to be gratingly tiresome given a bit of thought and time?

The problem is ultimately the psychological nature of any oliogarchic enterprìse.

Mass rectal productions are never foul, eh?

Right right. Left left. You lost me at rectal.

Those who have the most goats and water, win.

T’was ever thus.

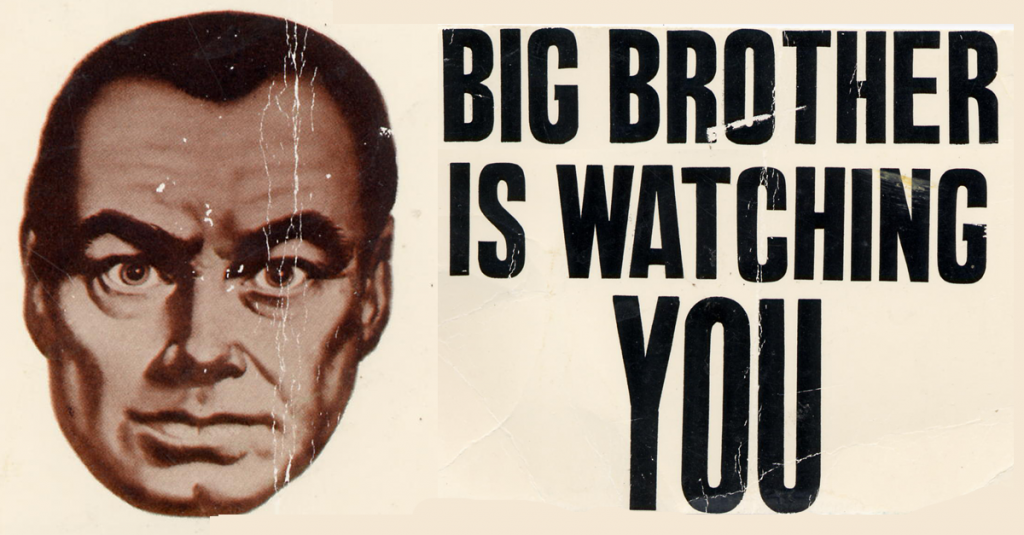

I love the fact that the original Big Brother poster was based on James Mason, a conscientious objector during WWII.

As a kid, I fell in love with him as Captain Nemo.

More recently, I was writing a fanfic about the fall of IngSoc through an act of misguided fandom by a young woman, who rushes the stage with a painting she’d made of him — and finds the “Big Brother” giving the speech is animatronic.

So does the audience as she falls in a torrent of bullets.

Most contemporary depictions of Big Brother depict him as a Stalin/Hitler hybrid — oppressive, yes, but not a face one could *love*.

I like this version.