Some histories tell us more about their narrators than their characters. The story of tattoos in ancient Egypt is one example. While tattoos and other forms of body modification have been part of nearly every ancient culture, Egyptologists have found many more tattooed female than male mummies at ancient burial sites. Since tattooing seemed to be an almost “exclusively female practice in ancient Egypt,” writes archeologist Joann Fletcher, “mummies found with tattoos were usually dismissed by the (male) excavators who seemed to assume the women were of ‘dubious status,’ described in some cases as ‘dancing girls.’ ”

There is no evidence, however, to suggest that tattoos in ancient Egypt specifically marked dancers, prostitutes, concubines, or individuals of a lower class (and thus of little interest to some early archaeologists). One mummy described as a concubine “was actually a high-status priestess named Amunet, as revealed by her funerary inscriptions.” Early archaeologists stubbornly clung to derogatory 19th-century assumptions about tattoos (and class, dancing, sex, and religion), even when discussing tattooed Egyptian women whose burials obviously showed they were priestesses or extended members of a royal family.

Until relatively recently, “the most conclusive evidence of Egyptian tattoos,” writes Joshua Mark at the World History Encyclopedia, “dates the practice to the Middle Kingdom” — spanning the 11th through the 13th Dynasties (approximately 2040 to 1782 BC). In 2018, however, researchers at the British Museum took another look at two naturally mummified 5,000-year-old Predynastic bodies, one male one female, dating from between 3351 and 3017 BC. They looked specifically for signs of body modification that might have gone unseen by earlier Egyptologists.

Known as the Gebelein predynastic mummies, these bodies are two of six excavated at the end of the 1800s by Egyptologist Sir Wallis Budge. Through the use of CT scanning, radiocarbon dating and infrared imaging, the British Museum has found that previously unexamined marks “push back the evidence for tattooing in Africa by a millennium,” the Museum blog notes, describing the findings in detail.

The male mummy, called “Gebelein Man A,” showed a design on his bicep:

Dark smudges on his arm, appearing as faint markings under natural light, had remained unexamined. Infrared photography recently revealed that these smudges were in fact tattoos of two slightly overlapping horned animals. The horned animals have been tentatively identified as a wild bull (long tail, elaborate horns) and a Barbary sheep (curving horns, humped shoulder). Both animals are well known in Predynastic Egyptian art. The designs are not superficial and have been applied to the dermis layer of the skin, the pigment was carbon-based, possibly some kind of soot.

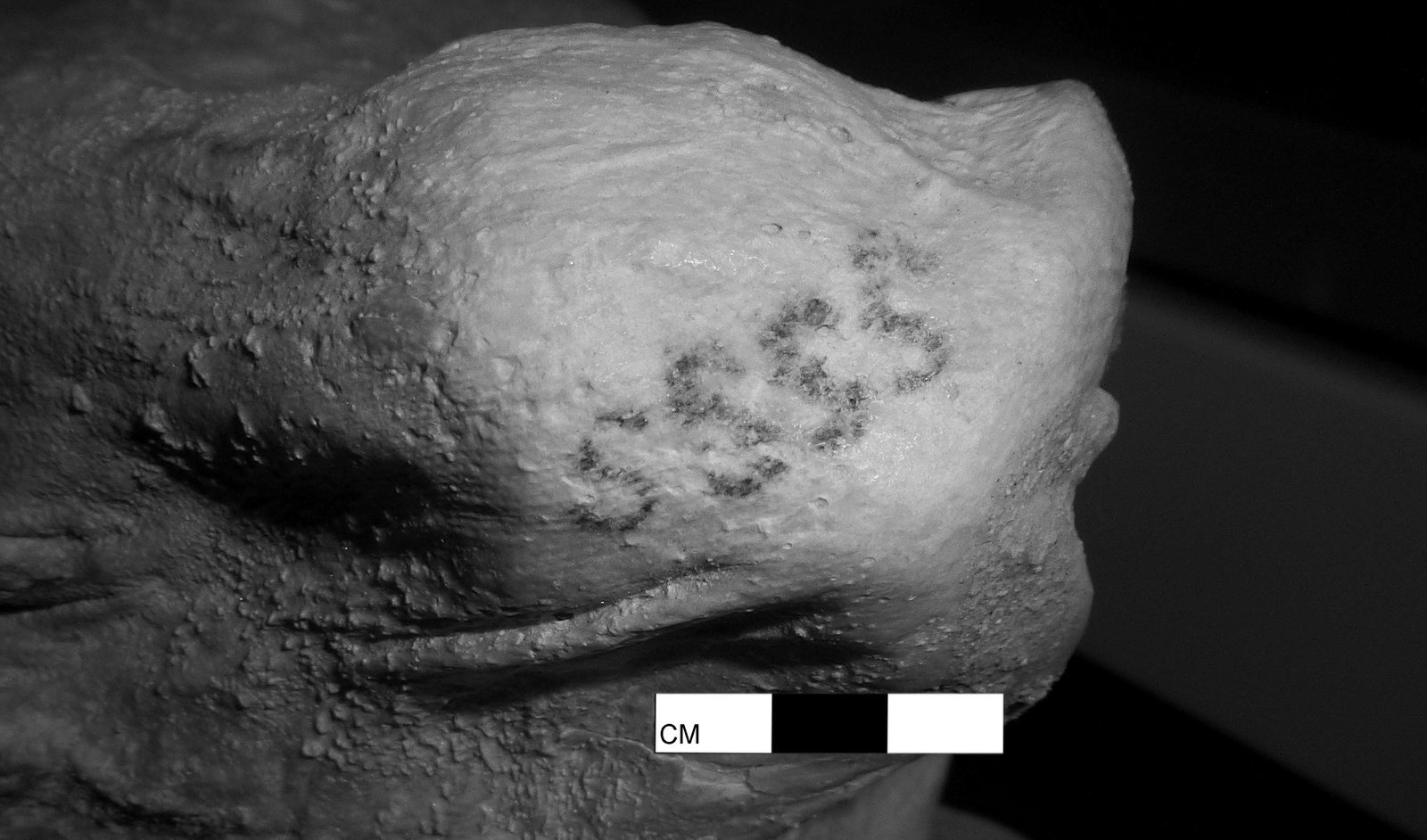

The female mummy, or “Gebelein Woman,” showed more intelligible markings:

[A] series of four small ‘S’ shaped motifs can be seen running vertically over her right shoulder. Below them on the right arm is a linear motif which is similar to objects held by figures participating in ceremonial activities on painted ceramics of the same period. It may represent a crooked stave, a symbol of power and status, or a throw-stick or baton/clappers used in ritual dance. The ‘S’ motif also appears on Predynastic pottery decoration, always in multiples.

In Middle Kingdom tattooing practices, a series of marks seemed to provide protection, especially in fertility and childbirth rites, functioning as permanent amulets or a kind of practical magic. Even if their meanings remain unclear, Marks writes, it does, “seem evident that they had an array of implications and that women of many different social classes chose to wear them.” And it does seem clear that tattooing was important to ancient, Predynastic men and women, maybe for similar reasons. Tattooing tools have also been found dating from around the same time as the Gebelein mummies, excavated at Abydos and consisting of “sharp metal points with a wooden handle.”

The dating of Gebelein Man A and Gebelein Woman place them as approximate contemporaries of Ötzi, a naturally mummified man covered in tattoos. Discovered in 1991 on the border of Austria and Italy, Ötzi was previously considered the oldest tattooed mummy. You can learn more about how the British Museum re-examined the Gebelein bodies in the “Curator’s Corner” video above with curator of physical anthropology Daniel Antoine. Read more about the findings at the British Museum’s blog and the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Related Content:

What Ancient Egyptian Sounded Like & How We Know It

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply