Few artists have anticipated, or precipitated, the fragmented, heroically individualist, and purposefully oppositional art of modernity like William Blake, a man to whom the cliché ahead of his time can be applied with perfect accuracy. Blake strenuously opposed the rationalist Deism and Neoclassical artistic values of his contemporaries, not only in principle, but in nearly every part of his artistic practice. His politics were correspondingly radical: in opposition to empire, racism, poverty, patriarchy, Christian dogma, and the emerging global capitalism of his time.

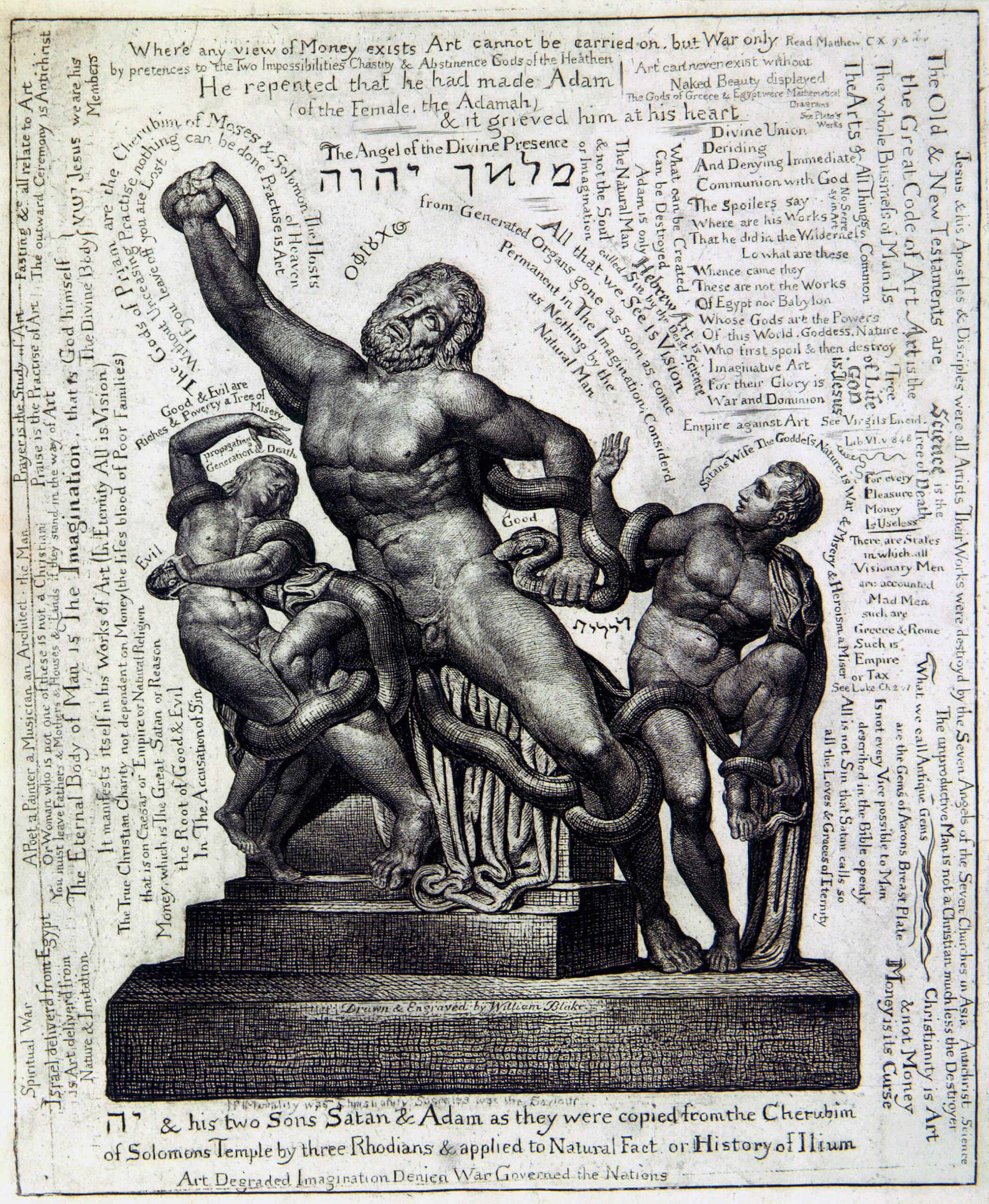

Nowhere do we see Blake’s visual radicalism more in evidence, argues Julia M. Wright in a 2000 essay for the journal Mosaic, than in his Laocoön, a work that not only seems to presage the modernist collaging of text and image, from Braque to Rauschenberg, but also looks toward hypertext with its nonlinearity, fragmentation, and intertextuality: “By combining as many as four different media in Laocoön — drawing, writing, engraving, and sculpture [in his depiction of the classical original] — Blake puts into play their different properties, engaging the debate in theory as well as practice.”

Through an art of visual pastiche, Blake resists the Neoclassical idea that visual art and poetry were mutually exclusive formal pursuits that could not coexist. (View a larger image here to read the poems and slogans that surround the image.)

We can see the influence of Blake’s radicalism everywhere, from zine art to the Blakes reproduced on the skin of special edition Doc Martens (the artist was also an enthusiastic defender of the Gothic over the Classical, Wright points out). An art like Blake’s demanded a radical process, and he conceived one through his professional skills as an engraver, an art he began learning at the age of twelve. “Right from his earliest childhood,” notes the British Library video at the top, “Blake was driven by two extraordinary and powerful aspirations. On the one hand as a poet, on the other as a painter… so how was he going to bring these two together in a form that would enable him to publish his own images in illustration of his own poems?”

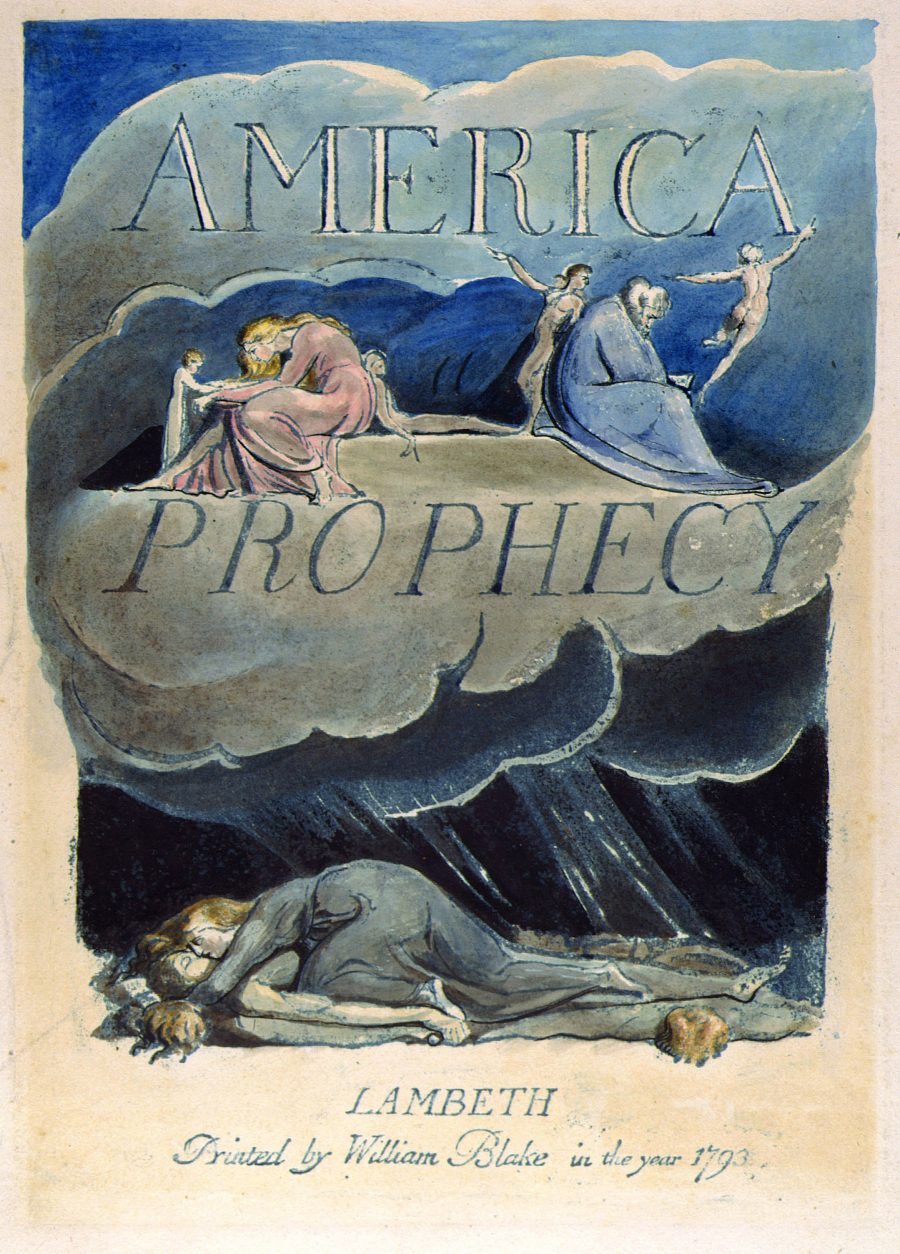

The video demonstrates “Blake’s innovation” as an engraver and printer. The printing process at that point involved a number of different specialized workers, some responsible for setting text, and others for separately printing images in blank spaces left on the pages. Blake’s process “enabled him, with the exception of the paper, to be responsible for every stage in the production process, from writing the poems, making the drawings, using the stop-out varnish to write his text, etching and printing the impressions.”

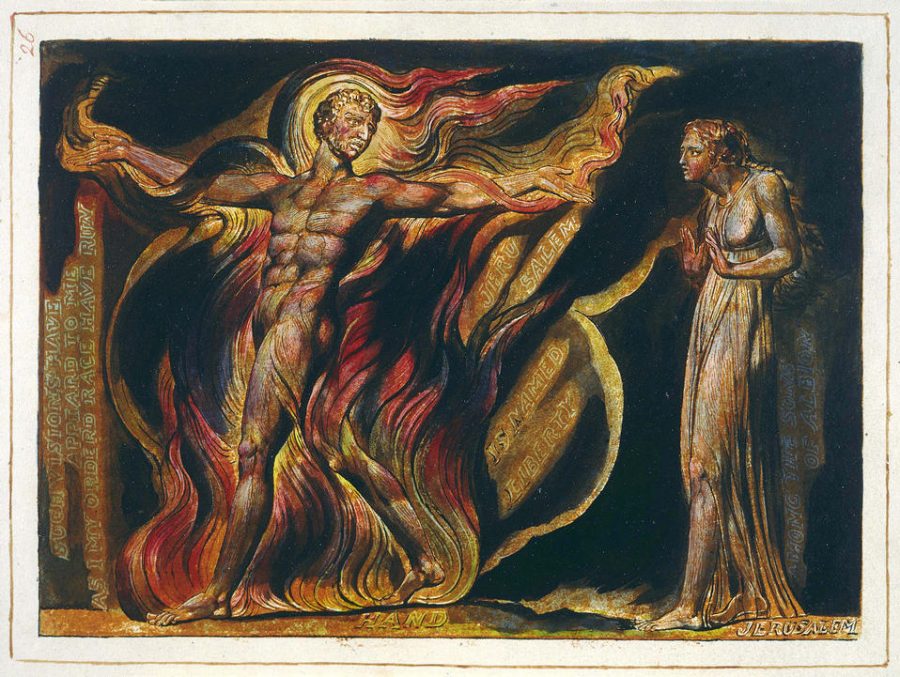

He began working out his methods as a teenager, and they allowed tremendous creative freedom throughout his life to create personal works of art like the “Illuminated Books” (from which the other two images here come): containers of his complex mythology and some of his most passionate engravings. You can learn even more about Blake’s DIY printing process in the video further up from Ashmolean Museum. Blake’s futuristic art drew heavily from the past — from Renaissance masters like Michelangelo, for example — as a means of creating an alternate art history, one that opposed the values of domination and oppressive systems of order.

His formal and political radicalism is perhaps one reason Blake became one of the first artists to populate an online archive, with the launch of the Blake Archive all the way back in 1996, “conceived as an international [free] public resource that would provide unified access to major works of visual and literary art that are highly disparate, widely dispersed, and more and more often severely restricted as a result of their value, rarity, and extreme fragility.” Visit the Blake Archive here to see high resolution scans of hundreds of Blake’s prophetic works, all created from start to finish by his own hand, and learn more about his personal and commercial illustrations at the links below.

Related Content:

William Blake’s Hallucinatory Illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

William Blake was the original mystic multimedia artist. Possibly a Freemason or Kabbalist.