It’s practically guaranteed that we now have more stupid people on the planet than ever before. Of course, we might be tempted to think; just look at how many of them disagree with my politics. But this unprecedented stupidity is primarily, if not entirely, a function of an unprecedentedly large global population. The more important matter has less to do with quantity of stupidity than with its quality: of all the forms it can take, which does the most damage? Robert Greene, author of The 48 Laws of Power and The Laws of Human Nature, addresses that question in the clip above from an interview with podcaster Chris Williamson.

“What makes people stupid,” Greene explains, “is their certainty that they have all the answers.” The basic idea may sound familiar, since we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture the related phenomenon of the Dunning-Kruger effect. In some sense, stupid people who know they’re stupid aren’t actually stupid, or at least not harmfully so.

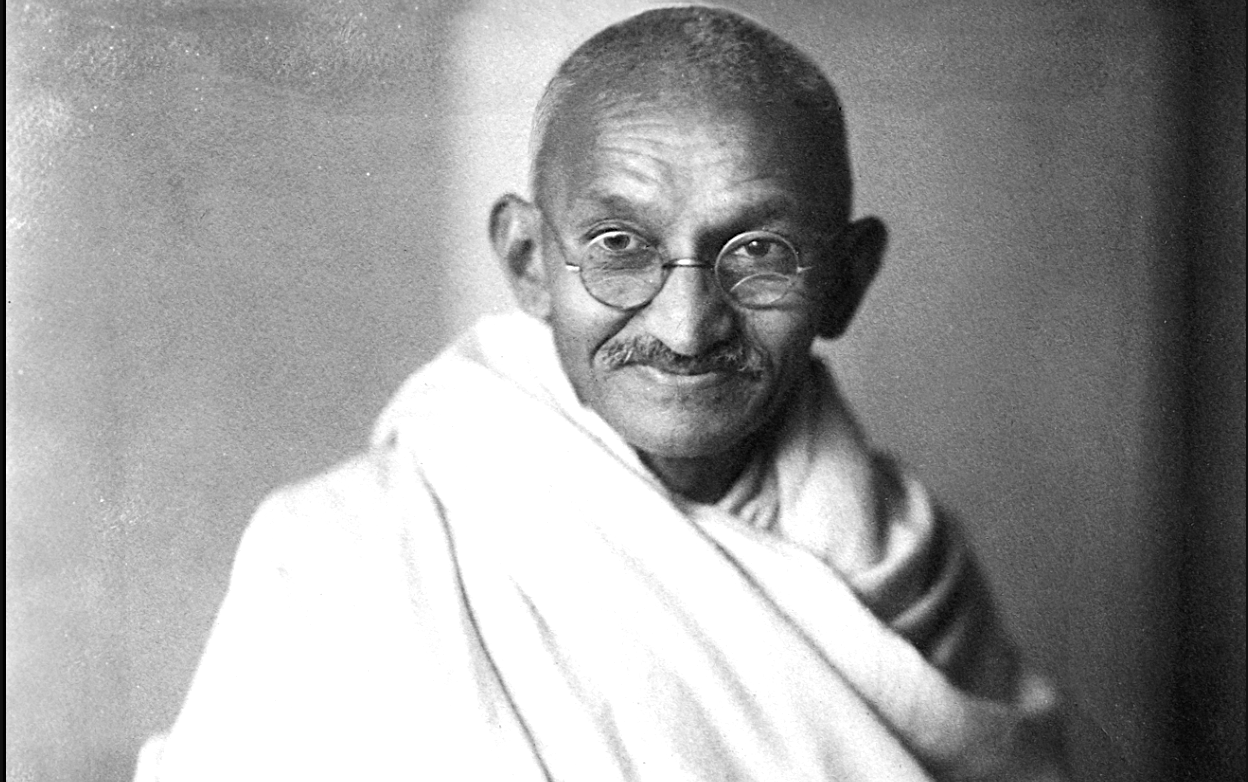

True to form, Greene makes a classical reference: Athens’ leaders went into the Peloponnesian War certain of victory, when it actually brought about the end of the Athenian golden age. “People who are certain of things are very stupid,” he says, “and when they have power, they’re very, very dangerous,” perhaps more so than those we would call evil.

This brings to mind the oft-quoted principle known as Hanlon’s Razor: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.” But even in otherwise intelligent individuals, a tendency toward premature certainty can induce that stupidity. Better, in Greene’s view, to cultivate what John Keats, inspired by Shakespeare, called “negative capability”: the power to “hold two thoughts in your head at the same time, two thoughts that apparently contradict each other.” We might consider, for instance, entertaining the ideas of our aforementioned political enemies — not fully accepting them, mind you, but also not fully accepting our own. It may, at least, prevent the onset of stupidity, a condition that’s clearly difficult to cure.

Related content:

Why Incompetent People Think They’re Competent: The Dunning-Kruger Effect, Explained

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.