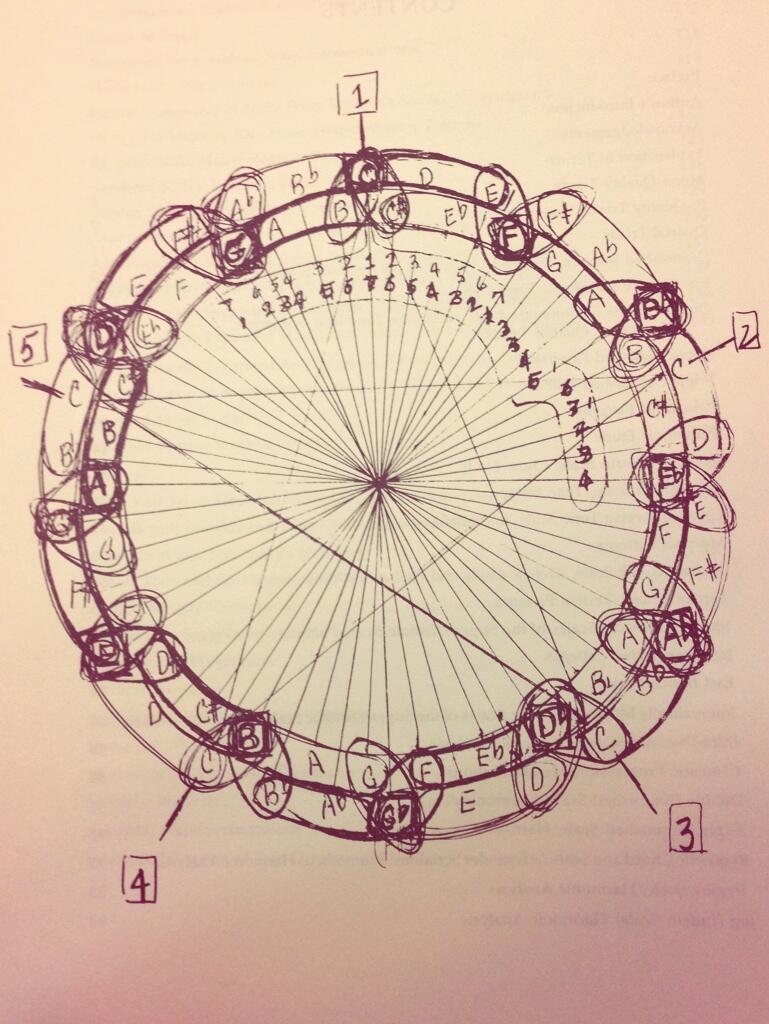

Physicist and saxophonist Stephon Alexander has argued in his many public lectures and his book The Jazz of Physics that Albert Einstein and John Coltrane had quite a lot in common. Alexander in particular draws our attention to the so-called “Coltrane circle,” which resembles what any musician will recognize as the “Circle of Fifths,” but incorporates Coltrane’s own innovations. Coltrane gave the drawing to saxophonist and professor Yusef Lateef in 1967, who included it in his seminal text, Repository of Scales and Melodic Patterns. Where Lateef, as he writes in his autobiography, sees Coltrane’s music as a “spiritual journey” that “embraced the concerns of a rich tradition of autophysiopsychic music,” Alexander sees “the same geometric principle that motivated Einstein’s” quantum theory.

Neither description seems out of place. Musician and blogger Roel Hollander notes, “Thelonious Monk once said ‘All musicans are subconsciously mathematicians.’ Musicians like John Coltrane though have been very much aware of the mathematics of music and consciously applied it to his works.”

Coltrane was also very much aware of Einstein’s work and liked to talk about it frequently. Musican David Amram remembers the Giant Steps genius telling him he “was trying to do something like that in music.”

Hollander carefully dissects Coltrane’s mathematics in two theory-heavy essays, one generally on Coltrane’s “Music & Geometry” and one specifically on his “Tone Circle.” Coltrane himself had little to say publically about the intensive theoretical work behind his most famous compositions, probably because he’d rather they speak for themselves. He preferred to express himself philosophically and mystically, drawing equally on his fascination with science and with spiritual traditions of all kinds. Coltrane’s poetic way of speaking has left his musical interpreters with a wide variety of ways to look at his Circle, as jazz musician Corey Mwamba discovered when he informally polled several other players on Facebook. Clarinetist Arun Ghosh, for example, saw in Coltrane’s “mathematical principles” a “musical system that connected with The Divine.” It’s a system, he opined, that “feels quite Islamic to me.”

Lateef agreed, and there may be few who understood Coltrane’s method better than he did. He studied closely with Coltrane for years, and has been remembered since his death in 2013 as a peer and even a mentor, especially in his ecumenical embrace of theory and music from around the world. Lateef even argued that Coltrane’s late-in-life masterpiece A Love Supreme might have been titled “Allah Supreme” were it not for fear of “political backlash.” Some may find the claim tendentious, but what we see in the wide range of responses to Coltrane’s musical theory, so well encapsulated in the drawing above, is that his recognition, as Lateef writes, of the “structures of music” was as much for him about scientific discovery as it was religious experience. Both for him were intuitive processes that “came into existence,” writes Lateef, “in the mind of the musican through abstraction from experience.”

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

John Coltrane’s Handwritten Outline for His Masterpiece A Love Supreme

John Coltrane’s ‘Giant Steps’ Animated

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Einstein’s theory of quantum gravity? I thought quantum gravity was a rebuttal against Einstein.

Einstein, did, however, like to make vague statements about God.

So can someone explain the drawing?

Its a circle consisting of 2 concentric whole tone scales. Not cycle of 5ths.

The 5ths are emphasized.

Ccb:

You’ll note that all the circle of 4ths/5ths notes have double circles around them.

This is an extrapolation of the circle.

That said, you’re not wrong.

here’s more…

https://roelhollander.eu/en/blog-saxophone/Coltrane-Tone-Circle/

NOt to take anything away from anyone…but the record should be seet straight. YUsef Lateef was NOT John Coltranes protoge. In fact they were peers who often practiced together and shared many ideas. It is common knowledge that Yusef was deep into “world music” long before coltrane and many others and that he was the one who introduced coltrane to schillingers system of composition from which giants steps was inpsired. It is not always the more famous one, of even the genius who comes up with ideas.…..this has been told to me by many who were around and on the scene at that time in detroit and nyc. Again..no disrespect here.…but it is good to know the untold story.

@Adam, thanks very much for your comment. I’ve edited the post to better characterize Lateef’s relationship to Coltrane.

@PaulR, whoops! Right you are. Corrected.

Here (as someone who was surprised to see themselves quoted in the article) to echo Adam Rudolph’s comments above.

lol Einstein always hate quantun mechanics!!!

D’oh

Alexander sees “the same geometric principle that motivated Einstein’s” quantum theory.

Gravity was not mentioned

Indeed, Einstein and Coltrain have something in common: they let math do all the ‘heavy-lifting’ allowing their imaginations to run free.

Melodic / harmonic analysis is moot without considering Coltrain’s keen sense of symmetric rhythmic phrasing – he always knew where he was going. Also knew the value of time-pitch ratios as being the most organic rhythmic phrases demoting the ‘bar-structure’ to being organization purpose only. My first experience with a 9 against 8 resultant (r 9 ÷ 8)was pure Coltrain(see Joseph Schillinger — Theory of Rhythm. Runs circles around any other so called rhythmic technique.).

Try this phrase (1 = 1/8 note– its 8 bars of 9/8 )

|: 8_1_7_2_6_3_5_4_4_5_3_6_2_7_1_8 :|

@Josh Jones: thanks for sharing.

@Corey Mwamba: why surprised? People who take blogging serious always make an effort to note proper credits. Your name would thus obviously appear.

At least for me your article “Way of seeing Coltrane” are of importance, without them I most likely would not have come to writing my blog articles. And perhaps Josh Jones wouldn’t have either?

It looks like to me he’s drawn the circle of 5ths opposite than most other versions- instead of going up in 5ths to the right he goes up 4ths to right and 5ths to the left- which imo, is a million times better. Also, Coltrane has spelled a couple wholetone scales, the top ring spelling out a C wholetone scale, and the inside ring is a C# or Db wholetone… Trane writes both scales four times each- indicated by the 1,2,3, 4, in boxes with a line going to the start of the aforementioned scales. I don’t want to look too much longer at Coltrane’s drawing, it’s starting to hurt my brain.. hahaha.… however, in the inner part of the circle it looks to like the small numbers and their accompanying straight lines are spelling out some chromatic scales. With all key centers flowing out from the center of the circle. Something like that.

where are you people seeing the 5ths and the 4ths in the circle? i just can see whole tone scales, chromatisms but nothing related with the traditional circle of 5ths.

And when you people, music critics and theorist are going to understand that MUSIC is not a f—ing SCIENCE, even if we use maths indirectly or some kind of rules..

The weird oval things connecting the two circles appear to be the “crossing points” between the circles to follow a major scale up to its seventh degree.

If you start at one of the double-circled fifths/fourths and proceed clockwise two steps, it describes do-re-mi, which are separated by wholetones. The mi-fa gap is a semitone, so you have to switch circles — and the mi and fa are connected in Coltrane’s diagram.

You can then continue on your new ring until you hit the 7th degree of the major scale, and you have the full scale, or you can cross at the 6th degree to land on the flat 7th (part of the dominant 7th chord).

I’m not convinced it’s hugely useful, because it doesn’t reveal more than other representations, and it obscures things like minor thirds and alternative modes of the scale, but it’s interesting to see how someone so deeply immersed in music tried to put down on paper what he had already grasped internally.

Actually, Einstein founded quantum mechanics in 1905. That’s why he had a Nobel prize in 1921. He hated how Niels Bohr solved some of the paradoxes of this quanta theory by saying reality was, at its core, not determinist. And quantum mechanics does not deal with gravity.

Jazz is a musical genre and it is difficult to define it without a broad vision that includes wide range of musical genres spanning over a period more than a hundred years. One should not disregard the role of improvisation in Jazz (Jass) music

It is all about music after all and physics, mathematics, cosmic rules of harmony should be connected to “music” and not to “jazz” only. This despises other genres of music.

There is mathematics & physics in everywhere. Not only in music but everything in the universe. When it comes to music, all genres of music contain in themselves mathematics & physics.

The two were very good friends. FACTS.

Stupid, very narrow minded. There are a infinite number of song and scales that do not conform to this map. As soon as you consider dissident scales the map goes out the window.

Total nonsense. This is just over reverence for Coltrane and nothing more. Coltrane wasn’t as profound as people pretend and that circle is nonsense. It’s heartbreaking, to me, how far off people are about harmony.

It’s a piano keyboard laid out in circular form. C1 being the bottom note on the keybord, then proceeding up by half step alternating notes to the inside and outside circles. Each “C” note is numbered as you pass it by on the keyboard until you get back around to the 6th, and start again. Any two notes with no black keys between them are circled. All the “C” notes are connected with lines. All the “5ths”, corresponding on the opposite side of the circle to their tonic notes, are connected with lines. I’m still tying to figure out what the numbers inside the circles refer to.

Hey Roel! It was shared by someone on FB, and I was reading it; it just came as a surprise!

Coltrane and Lateef studied with the mathematician, jazz theorist Roland Wiggins in Philadelphia. He introduced them to Nicholas Slominsky’s thesaurus of scales and melodic patterns which was fundamental to Coltrane’s methodology .

This looks like it is based on a 12 tone melodic pattern.

I just realized I’m actually wrong about the circled notes.

I would love to see another blog in which you completely dissect this diagram, note by note, line by line.

Yusef Lateef ( William Evans) was member of the Dizzy Gillespie Orchestra around the same time that John Coltrane shared the sax section .…. end of the forties and early forties . Jimmy Heath was also in the Dizzy’s Orchestra…

For the musicians interested, here’s an old article dated back when the picture was posted by Miles Okazaki on Twitter :

http://www.coreymwamba.co.uk/rambles/1388150764

Btw, i have the digital version of the Yusef Lateef book somewhere on my hd, and if i remember correctly there are actually 2 Coltrane drawings in there (pretty much similar but with a twist from what from what i could recall)

“good” music, is timeless in a sense that it tickles something in our brain. Almost as if we have heard it before? There is a magic and beauty in music , when it is “right” it brings pleasure and triggers emotions.

There is something magical about mathematical models and algorithms, they are beautiful, timeless … They just work…

They may describe some “thing” or property of physics, that inexplicably IS THE TRUTH, music is the same in a sense, No one can deny the POWER of sound waves , that touch the heart in a way that can’t be explained easily, but is are real and timelessly truthful as mathematics itself😊

Einstein’s physics was not quantum. Even though the term is older and due to Planck, who started it all in 1900, Einstein, seen erroneously as the last classical physicist, was not thinking in those terms yet. The assertions in the article are intriguing, though, and the book could be that, too.

Intellectual complexity in music is not a hard achievement. One can have a computer come up with plenty of complexity. What is hard is accessing genuine inspired creativity expressed via apparent simplicity/complexity. Todays and the past 40, 50+ years of music is exclusively for the general public and average musicians at best. No longer do we have musicians who can create real art for the best musicians in the world, just as we no longer have Shakespeares or Beethoven’s any more.

This is so visually stunning, the harmony and Sacred Geometry of music, charted as in Astrology in a combined sphere!!! Next level!!!

Does anyone else think that this looks really similar to Metatron’s Cube?

I think you mean “dissonant” scales … not “dissident.”

I see an extrapolation of the Circle of “4ths” (a square is drawn around each “4th”). Then the circle was subdivided chromatically up a 5 octave range. Then circles were drawn to highlight the half step approach note below each 4th (leading tones) and a circle was drawn to highlight the half step up above each 4th (tritone chromatic approach).

The Chromatic scale degrees have been numbered 1 2 3 4 5 6 7, 1 2 3 4 5 6 7, for organizational purposes.

This is simply a sketch of the chromatic scale, then highlighting the circle of 4ths within it and circling each ones leading tone and chromatic tritone approach note. This is pretty basic stuff.

Here’s another interesting analysis of this circle … http://www.coreymwamba.co.uk/rambles/1388150764

This essay addresses the apparent ‘mistake’ in the left side of the circle where the pattern of three chromatic tones is broken. There is a second version of the circle in the original notebook which ‘corrects’ this mistake. The groupings in the overlapping ovals are all set up so that there is a single note between each grouping in both the inner and outer circle, but one of the groupings ( G, G#, A) is off and should probably have been G#, A, Bb. There is a lot of debate about whether or not this was a mistake or intentional, but in light of the second sketch and simple logic, I think it’s essentially a minor error in the sketch which was left uncorrected in the tradition of zen art, and of course Jazz, where mistakes are also not mistakes.

Here’s another examination of this circle, including observations about the apparent mistake in the left hand side of the circle. (two part blog post)

http://www.coreymwamba.co.uk/rambles/1388150764

http://www.coreymwamba.co.uk/rambles/1388289138

The chromatic groupings, surrounded by overlapping ovals, are all positioned with one note between them in the inner and outer rings, except the grouping “G, G#, A” which is off by one place. It probably was meant to be “G#, A, Bb” which would have been consistent with the rest of the pattern. There’s a lot of debate about whether this was really an uncorrected mistake or intentional. On the side of it being a mistake, there is a second sketch in the same book showing a ‘corrected’ version.

His relation to quantum mechanics was more complicated than that:

https://theconversation.com/einstein-vs-quantum-mechanics-and-why-hed-be-a-convert-today-27641

I wonder if any of you folks remember my father, John Clough. Music theorist who theorized “flip flop circles” Brilliant man. I miss him.

John Coltrane grew up Pentecostal which means he prayed in the Spirit that is in tongues in the Holy Ghost.

He was a perfectionist.

As far as beliefs he seemed to embrace Eastern like spirituality later in life.

But then why was Coltrane found dead on a park bench in Central Park in NYC?

Talent without restraint and strength of character makes ones gift somewhat void.

You can see the theory behind Giant Steps in this circle.

Using the inner circle’s darkly circled notes A, B, Dflat, Eflat, F G

and the outer circles darkly circled notes C D E Gflat Aflat Bflat

In giant steps. All Major Chords Eflat, B, and G are in the inner circle’s darkly circled notes. All dominant seven chords are in the outer circle’s darkly circled notes. Minor chords are functioning merely as appendages of the dominant chords.

Try playing with this: The two circles allow for substituting surprising dominant seven chords to move in surprising directions:

Conventional: G D7 D

Conventional Jazzy: G D7 to Dflat

Using this circle G Bflat7 to Eflat (see first line of giant steps for this move.)

How bout this G E7 A ?

Each one of the above moves uses a major chord from the inner circle a dominant from the outer and resolves down a fifth to the inner.

The article referred to Einstein’s “quantum theory,” not theory of quantum gravity. Huge difference there. Also, although Einstein is most famous for his theory of gravity (general relativity),he is credited with being a pioneering of quantum physics. His nobel prize is for the Photoelectric effect(quantized light/counting photons).

Also, quantum mechanics/physics isnt a rebuttal against Einstein. We simply cannot describe the behavior of nature at very very small scales in a “classical” way, that is, deterministically. His gravitational theory is just fine for general purposes. In fact NASA still uses newtonian gravity/mechanics something even less accurate.

You might be thinking about the fact that Einstein did not accept the fact that the mathematics formulated to address the apparently quantum nature of matter was based on the statistical probabilities of it being in a certain place at a certain time. He believed that they simply had not yet uncovered the variables which truly and precisely determine the behavior. He was ostracized for this of course.

Quantum gravity is the attempt by many physicist, from Einstein to today to unite quantum mechanics and general relativity. So the idea that one rebutts the other is just a false misconception. The problem is that the two work extremely well in their own domain.

By the way i love jazz, coltrane, mathematics, physics, this article, and of course A Love Supreme.

It’s all the golden ratio

Call me crazy, but I think part of the diagram is wrong:

As you look to the left and the 9 o’clock position one of the “hearts” is facing the wrong direction. The bottom of the heart should be the note A which points towards the inner part of the circle.

Anyone else catch this or have further comments on it?

And not a word about his theory or technique.

Becoming a father for those who will follow the deeds; which may help in the science and in state of the art achievements must be that this person is a fine influence for those.

May they be recalled in all goodly deeds, in the good light for-ever. Salutes in peace.

While reading through the comments and replies i am mystified as to how many times those individuals who’ve commented or replied have misspelled John’s name…it’s Coltrane not Coltrain…i find it totally disrespectful to do so!!!

You can see the circle of fiths or fourth in it.

Coltrane

John Coltrane died at Huntington Hospital in Long Island of liver cancer. We can argue about the cause of his cancer and if his history of drug abuse was a contributing factor. Your description of him as dying destitute on a park bench is false.

I think “the same geometric principle that motivated Einstein’s” General Relativity” might work better. General Relativity involved a lot of Geometry.

While Einstein argued with famous Quantum Mechanics proponents like Niels Bohr, he in fact was one of its originators whether he liked it or not. Einstein’s paper on the photoelectric effect showed that light was both a wave and a particle which is one of the bedrocks of Quantum Mechanics.

IIt seems someone is double-guessing Bach and Mozart. This was far better illustrated on a training card in the 1960s.Shifting singers formant frequencies is far more interesting.

Don’t need any kind of cheap literature to undestand what’s he doing. You see the draw and instantly knows what means and how to play it. There’s no need to stupid mistycal references, take care that people talking calls brian eno a futuristic composer…

looks more like stalin’s notes at a debussy concert

Pure nonsense. There have always been and will always be innovators. The problem is that they belong to the age they come from and not to pre-established aesthetic ideals. There are plenty of composers, writers, painters, poets, etc., who will be recognized for their tremendous innovative strides in this age, but the chances are that you’ll never learn about them — they may not even be known outside of a very small circle of people for another hundred years. Shakespeare was relatively unknown during his lifetime and then disappeared until a revival of his work much later. Bach was pretty much completely forgotten. The other thing is, if you’re looking for “real art” to sound like Beethoven or read like Shakespeare, it’ll never happen — art is evolutive — it reflects the changes that we experience on a sociocultural level, as well as fundamental shifts in awareness. Please remember that many of the artists that we’ve made into icons over the years were never popular in their own time. Popularity is never an indicator of quality or innovation.

@ Ziga, Innovation by itself is not Art. Art is a communication of a ‘higher consciousness’ via matter to give us a glimpse of that state. It is the best evidence for an ‘after life’ (whether you believe in such or not) and said higher consciousness. Innovation many times comes from talent (mental instincts) and tend to have a ‘deadness’ to it. The music of Beethoven etc. does not come alive and show its true potentials in any of todays musicians. Also classical music cannot be recorded. Non classical generas hide behind amplification for appeal. Not that i’m against pop music btw.

Many years back I got to hear a musician who could channel the super conscious (if you want evidence-not proof for the super conscious:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pzd7ReqiQnE) mind via the instrument (with a real vibrato). He got this gift after an auto accident. Only then did we hear what beethoven’s music was supposed to sound like. The entire audience was professional strings players from around the world (unlike the general public who jump at anything). None had heard anything like it before or since.

One cannot appreciate the depth of the music of Bach, Beethoven and Mozart until one has heard a real musician in live performance. An extremely rare event. They no longer seem to be born, or the gifts or not available as they once were.

Even the Jazz greats are supposed to be all dead according to some jazz musician who lamented on the Charlie Rose show. We’ve always known that in the classical world. So you cant judge classical until you’ve really heard it.

Back in the late 90s I came across this drawing in Lateef’s book and studied it closely. I found that it actually describes not a circle but a torus (aka donut) with a string winding around it. There are versions of the torus for all the symetrical intervals (semitone, whole tone, minor third, major third).

I diagrammed each of these, and shared my work with Lateef. We had a warm conversation.

He mentioned to me that “Coltrane was always drawing things like this.” This particular drawing was something Coltrane did between set breaks at a gig they did together. He gave it to Lateef at that gig.

Mr. Callaway, where do you get your information? Clearly not from any factual source. “A park bench”? “Strength of character”? It’s like The World According to Sean Spicer.

Coltrane is the correct spelling.

Above all else, etc! Coltrane’s lyrics, A Love Supreme and ”

Astral Travel ” and Einstein, ” You can’t Solve A Problem, Frim the Same Consciousness That Created It, You Learn To See The World Anew.” Nuff said by two of the most culturally competent spiritual genius giants who stepped on this planet ions ago, yesterday, today, and tomorrows will be relativity in cosmically sweet eternally.

He got close, considering he used a 2D scheme. The solution to his mathematic breakthrough I believe correspond to the more accomplished “torsion field”; which, resembles the energy expansion and compression toward an infinite external rout and a single internal one.

Einstein received his Nobel Prize for discovery of the photoelectric effect law

Brilliant,well spoken @ZIGA

Yes! I agree. ‘any musician will recognize as the “Circle of Fifths’ really isn’t helpful. This isn’t what any musician would recognise as the circle of fifths. I suppose you could say the 5ths are circled, but actually every single note is circled at some point in the drawing! Sure, you can pick out the 5ths if you know what they are, but I don’t think that’s what the image leads you to do that. If anything he’s highlighted C five times with numbers…which is…helpful? I pretty, and I imagine drawing it while you thinking about music is probably fun, but not especially useful!

Also there is a cycle of fifhts,watch carefully and you will recognise Ccb

Chinese American Dr Chou is the first (woman? person?) to hold two chairs in seperate departments: Music and Math at Harvard. Her sister was the secretary of Education in China, her mother wrote the first Wok cookbook and her father was the only person to speak all of the Chinese dialects (200?) . Watched him correct a word on the wallpaper at a Chinese restaurant in Berkely.

Jean you are the only person who got those points correct. It was the discovery of the photovoltaic principle being quantized that won the Nobel. And quantum gravity was never considered in Einstein’s time, and only considered as part of the attempt to reconcile relativity with quantum mechanics.

This is all nonsense. Coltrane was a brilliant musician, but it can be understood and appreciated (and played) without reference to Einstein and math. Just because someone says that musicians are subconsciously mathematicians doesn’t make it true.

The article is just a collection of unsupported statements and more or less irrelevant quotes. And if it “feels Islamic” to one clarinetist doesn’t make it Islamic. Coltrane was influenced by music from Africa and India, to be sure. This appears to be written by someone with little grasp of harmony, and a desire to be seen as deep. To a musician who’s worked on Coltrane’s music it’s somewhat embarrassing to read.

Your comments are elitist and narrow.

When the arts transform you know you have arrived in a world you are heading for.

Interesting comments on what the Coltrane diagram might represent. But HOW do you suppose Coltrane used it? Listening closely to his music might give insight to his use of this diagram to illustrate an intellectual grasp of his intuitive musical underpinnings. To focus on the rings is to miss a more subtle point and drown the conversation in intellectual sparring. The key is not found in the ring(s) themselves so much as it is found in the place where all the lines converge in the center. To Trane, I believe, the outer rings = human intellect (excellent for its intended purpose, but limited. The point where all lines converge = intuition (or perhaps for him, Spirit/Oneness). Coltrane, particularly in his more ‘spiritual’ work, did his sincerest best, as most musicians do, to replace ‘thinking’ with ‘feeling’ and thus, become more musically (personally?) transcendent.

It’s funny we make all this analysis about music assuming there are only 12 notes. There are infinite notes, just as there are infinite colors. The 12 tone system is convenient, but merely 12 points in the realm of infinite possibility. If we want to find real parallels between music and other realms of science/experience, we must look at the other aspects of sound/music. Exploration of the overtone series is a good place to start! Why not tune our musical scales to points on the overtone series? Much more harmonious and beautiful!

I HAVE BEEN WORKING ON SIREALISM FOR ALMOST 17 YEARS AND I FIND MEANING ON THIS GEOMETRY OF JOHN COLTRANE IT HAS THE MUSICAL MATHEMATICAL INDEPENDENCE OF THE UNITY 1, WHICH HE ALLOWS THE 4TH DEGREES TO BE THE EQUILIBRIUM CONSTANT WHICH DYNAMICS THE VALUE OF OTHER SCALE DEGREE SYSTEM IN DIFFERENT EQUALITY AND HARMONIC EQUIVALENCES.

These concepts are all in the Schillinger System of Musical Composition.

It actually doesn’t say anything about ‘quantum gravity’ (which applies more broad quantum theory to the relatively narrow field of gravity). It’s actually quite interesting to think of Coltrane’s musical theory as being related to ‘quantum theory’, as western music and instruments arguably under-quantify tonality.

In 1968 I was listening to a Coltrane album. I cannot say that I know what a “trance” is, but that’s the word I’ll use. I went into a trance. It was not something I was trying to do.

During the trance, Coltrane’s music translated, in my mind, to words, sentences, paragraphs of the English language. They had very specific meanings. When one side of the album ended I would eventually wake up out of the trance. I could not remember the English translation that I had heard while under the trance.

I’d flip to the other side and play that side. I’d go into the trance again, and the same thing would happen. And NO, I wasn’t high. Yeah, it was the ’60s, but I never got involved in the drug crap.

Of course, I have long wished to know what had happened back then. Did Coltrane DESIGN his music in that manner? By the way, I had not known a single thing, back then, about Coltrane’s spirituality. To me, it was just “good jazz.”

Anyway, this article blows me away, because, in a way, it somewhat “confirms” for me that Coltrane was some kind of esoteric scientist or something. And I wonder if some scientists and/or mathematician could study Coltrane’s music and possibly derive, scientifically, some kind of relationship between the mathematics/physics of Coltrane’s music and the English language–or perhaps ANY language.

When one thinks of the idea of morphogenic fields, collective consciousness (or the collective subconscious), then perhaps it can be imagined that the experience that I had in ’68 could have been duplicated by anyone, of any culture, who would have heard the translation of Coltrane’s music in their own language.

It’s a nice drawing, for sure. But I’m afraid it’s just a matter of over-hyping Coltrane. People like to talk about Coltrane or Miles Davis like they were super humans, and people feel it’s really trendy to hype them.

But actually, as great as they were, there are thousands of other jazz greats who are just as genius, if not more, but receive little or no attention at all. I guess it’s not fashionable to praise Count Basie or Dizzy Gillespie.

It’s a matter of hype, fashion, and ego. To talk about Coltrane makes you look so profound and knowledgeable… it’s just an act.

Not a single person has mentioned Dennis Sandole, Coltrane’s teacher, and the person who showed Coltrane how to split the octave into three equal divisions. For a more interesting “Sacred Circle”, check out Pat Martino, who arranges the chromatic scale in a circle (similar to a clock face). Martino lays either a triangle or a square over the circle, which gives either an augmented chord or a diminished chord. Martino then generates every type of chord by raising (or lowering) successive notes in the augmented or diminished chords by a half-step. This is a completely different approach than generating the chords out of the major scale. Note that Martino was also a student of Dennis Sandole, and note that again we are talking about someone who is splitting the octave into even divisions of either three or four.

Are you sure about the schillinger system thing? With reference to Giant Steps though and apart from “Have You Met Miss Jones” bridge I always thought it was the Slonimsky Melodic Patterns

You’re right about Yusef Lateef though because Trane was interested in Indian Ragas which Layeef showed him.

I have never read any influence regarding Schillinger though please clarify

Very true. Making assumptions about music based on Western modalities is ethnocentric. An example of an alternative is the Persian Dastgah system.

Good you mentioned Dennis. Thank you.

An exceptional and pioneering artist. The mentioning as well as the speculation of the influence(s) that supernatural myths had on John Coltrane add to our understandings. Thank you for sharing about these numerous insightful glimpses into John Coltrane’s life.

It’s the cycle of 4ths, not fifths. He clearly has 4ths cycle circled the darkest. 4ths are V7 to I and knowing the cycle helps tremendously. It is also the order of flats for key signatures. Coltranes abilty to play modal is written all over this sketch.

This drawing is based on equal temperament, which is a false construct altogether. Hard to apply pure math and look for meaning in something people made up. Equal temperament is a mildly adulteration of a truly remarkable set of numbers and ratios. Even the notion that an octave contains only 12 notes is instead wrong except for in western tonal music. When Bach and others tweaked nature in order to construct instruments that could play in several keys, they left the natural math behind altogether. So this is a drawing of 12 equally spaced ‘things’ in a circle and various geometry connecting the dots. ( geometry is enticing because it implies order within chaos- but it usually has to ignore a lot of the chaos to do so. ( constellations much?).

NOW, if someone wants to re-draw this over a Just intonation / harmonic series with perhaps a 56- note karmic Indian ‘scale’ ( aka round number selection of harmonics- halved until they all live within an octave, THAT would probably blow some minds, too. I think it would look like a spiral galaxy in 3 dimensions. Perhaps a computer modeler would help. It probably already being done in the context of weather modeling programs.

Anyway, I think Coltrane’s point is: it’s all miraculous and bigger than us from a higher power and that will always hold true.

With regards to Schillinger’s influence pure fact. Yusef Lateef studied the Schillinger System in Detriot and his influence along with many musicians of the day, Juan Amalbert, Muhal Richard Abrams, Jymie Merrit, Jimmy Heath …

I’ve always thought that music is mathematics. Just look at notation, pitch is vertical, rhythm is horizontal- a simple graph. Granted, I’m speaking of western music. but has no one noticed that connecting all the C’s on the chart produces a beautiful five point star? That’s the connection between music and math!

Read the article again. It credits rightly so as you note that Yuseef was “peer even as mentor” to Trane.

Min

Einstein made one early contribution to quantum theory in 1905,before his famous papers on relativity. Other people elaborated the theory. The biggest problem in theoretical Physics is that quantum mechanics doesn’t fit smoothly with general relativity, even though each theory works really well in its own domain. Einstein himself worked on the Unified Field problem without making much progress.

The article doesn’t say quantum gravity. It is possible that the author misspoke, knowing more music than physics.

How in any way is this 8 bars of 9/8? You don’t teach music, that much is clear.

It may be a real possibility that Coltrane had Synesthesia. Many brilliant people do. It has the brain thinking in colors, or numbers, or drawings to sound, taste etc. It’s like having hyper sensitivity in brain portals. It would explain all of it, and is not something most people understood, or understand today.

The pentagram in John Coltrane’s drawing may well be the circle of fifths etc BUT it may also be the orbit of Venus, the Goddess star.Why?John Coltrane was, I believe, [and one of the great “Goddesses”/psychic priestesses has confirmed} the reincarnation of Elijah,Christ and the Prophet Muhammad {pbuh} and that’s what he discovered in 1955, but never said. The true Christ “Anointed one/God’s messenger“ never claims anything for himself — he leads by example.

I believe John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” was his New Testament/Qur’an, released in the universe language of music, and that his agonised late playing expresses his great sadness that his beautiful Buddhist message over many incarnations had been totally misunderstood and led to so much hatred — he was crying out for our help, for our understanding.

It may even be that only the great psychic priestess Alice Coltrane knew who John really was, that only she truly understood?

Think if we don’t listen and stop fighting over religious differences, like Prospero in Shakespeare’s metaphysical masterpiece The Tempest, we will condemn him forever to his island of sadness.

If you lazy iconophiles could bother yourselves to learn even the most basic music theory — European, Indian, Arabic, it doesn’t matter which — none of this poppycock would be impressive at all.

Charles, I believe you are spot on. I would add my belief that his influences extended beyond Africa and India music. ( I am sure you know that :<)

Not meant to be critical at all.

Symmetry is the order of our universe. In the Genesis, the world was formed, Not a fairy tale but true. The Bible is nothing but science. We don’t want to acknowledge this truth, but everything compliments one another. Thank you for sharing.

You obviously dont understand the dynamics of dissonant jazz, which was very highly practiced and played by Coltrane. This chart is not about harmony, at all. It is about format and function by which he strategized his compositions.

Daniel — I studied sporadically with Wiggins at UVA in the early 90’s. I’m wondering if your comment here signals that you did, too.

No one chooses the time and/or place of death.

These harmonic geometries dissolve when one removes temperament from the equation and use naturally occurring intervals. Coltrane/Slonimsky geometries only function in the 12-tone equal tempered system, that is, they exist within a cultural bubble. They are more of a linguistic grammar than a natural physic.

Is American indigenous singing and drumming “music”. Has it or can it be analyzed as “music”?

It’s just two rings depicting the two whole-tone scales. It’s no surprise that a six-note whole tone scale will repeat five times around a circle of 30 notes, leading to a pentangle diagram. Claiming that a diagram like this has a connection to Einstein’s theories is like claiming that a tic-tac-toe diagram shares a deep connection with quarks.

Yeah– I was hoping for the same thing. I’m neither a musician nor a mathematician, so I had hoped someone would break down this drawing and explain what it’s supposed to be showing. It’s a great drawing (I’m a visual artist) so it looks fantastic to me, but I have no idea what any of this means or how it relates to anything.

Love respect Namaste

Watch this. I always felt this captures the description of Coltrane’s creation best.

https://youtu.be/62tIvfP9A2w

It’s always amusing to read commentaries purporting to find Islamic inspirations or analogues in Western music. In Islam, listening to idle singing or the playing of musical instruments for mere pleasure is “haram,” forbidden; Allah will pour molten lead in the ears of such persons on the day of judgment. Here is a reference, from the Permanent Committee of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; others can be found.

http://www.alifta.net/Fatawa/FatawaChapters.aspx?languagename=en&View=Page&PageID=10282&PageNo=1&BookID=7

I see a spiral, not a circle.

Fascinating–how the worlds of the Arts, Physics, Quantum Mechanics, and Spirituality can intersect.

I also perceive in “the Coltrane circle” what Spanish and international artist Pilar Viviente renders her own way in her colorful series of “Rodetes.”

“Only connect,” the great English writer, E. M. Forster advised at the conclusion of his masterpiece novel.

We are already connected. We are already connected. The best artists and scientist and spiritualists endeavor to better understand, refine and illuminate those connections–in their own way.

he did not found quantum mechanics — in fact he railed against it for most of his career. He did establish the special case of relativity and general relativity. Neils Bohr, Max Plank and manny others establish quantum mechanics

It all depends on the music, that was created, as we know the sound creates vibration and the vibration can create shape. The Pentagram shape shows what type of music the musician who drew this, is creating. As being myself someone who creates music, and created various types, styles and genressince 2009, which you can listen on Spotify for example, I understood the light side and the dark side of the music.

Yes, it connects to some sort of spirituality and the divines, but as Alex Jones recently stated well, on Joe Rogan podcast, the good angels-spirits won’t intervene in your free will, but the bad ones will. So, making music is like channeling, where most of the musicians probably don’t know who or what they are connecting to.

No need to base it towards Einstein or quantum whatever theories. The stuff is there, it’s happening, and those who are woke enough, and make things like music and arts, can feel it and know it exists.

Regards,

That is just cow poop. Look harder. Widen your field of inquiry. That’s as stupid and elitist as saying, “Painting is dead.”

From what I see there are 5 numbers on the outside of the circle all pointing to C. These five points are joined by a 5 pointed star. The research says that the note C vibrates to the root chakra and corresponds to the vibration that the earth vibrates to. As one may go up the chakras, the notes corresponding to each chakra follow the C Ionian scale ending with the 7th chakra located on the top of the head. Each one of the darkened circles outline the circle of fifths which are surrounded by the upper and lower neighbors of the darkened notes. The outer circle of the circle outlines the whole tone scale with the starting note as C. The inner circle outlines the whole tone scale starting on A or any one of the notes of that whole tone scale. The lines in the middle of the drawing connect to the tritones for example the C connects to F#, A to Eb etc. These dominant chords are interchangeable as the thirds and sevenths are just reversed in position. The numbers in the middle of the drawing on the lines are numbered from 1–7 starting on for example C and ending on the tritone F# moving chromatically. Then there are numbers under those which move backwards from C to F#- the tritone . There are other numbers drawn on the lines which don’t seem to be completed and also seem to be crossed out. So all this being said, my take is that this is a drawing of relationships and connections. I’m still not sure how this is used when playing but that being said, I do think of the upper and lower neighbors when I am playing a scale or chords to give my solo contrast and musical tension. By the way, thank you so much for this post! I’ve been wanting to really study this for a while now and this gave me the opportunity to do so!

I see there’s no mention of George Russell’s Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organisation? Probably good to acknowledge the importance of this text in relation to Coltrane’s developments with harmonic movement.

That is the first time I’ve learned as much from the comments as from the article. Congratulations you all.

I just wish I had a deep and thorough understanding of math and physics. I only have the questions.

Thrice you mispelt Coltrane’s name in your text. Is this deliberate or are you talking about someone else ?

This is perfect.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=62tIvfP9A2w

love the music man

Yusef was in the group AFTER trade. he was recommended by and replaced James moody who had a hit record out and so left dizzy.

Just to add to this conversation and to address those of you who wish this circle to be “everything” . Coltrane, Yusef Lateef and Eric Dolphy spend alot of time researching and practicing together. they made many diagrams similar to this one. No one circle or diagram was ever meant to “show it all” I have copies of several others of these. This one has become more know because Yusef included it in his important book “Repository of Musical Scales and Patterns” and Stephon used it — with permission in his book. It shows only SOME aspects of the intervallic research these 3 were doing and the kind of work Yusef did up into his 90s. Nothing is craved in stone. The idea was and is to find YOUR OWN way.

Brandon…there are many to acknowledge…no one worked in a vacuum. Coltrane developed his own ideas in his research …his peers„„Dolphy, Ornette, Lateef…were all looking into how to organize and move through intervallic material.…As Yusef told me…“when you get rid of one thing, you have to replace it with something else: they had moved beyond working with “chord changes” thus the interest in intervals. George Russell was very important to everyone and we have to also mention Dizzy, Barry Harris, Monk.….I call them the R & D musicians. they showed us all the PROCESS. (it is not about style)

What if, space is curved, and, if we don’t get lost, we won’t find ourselves, dancing!

@andrew hill You’re absolutely wrong. Einstein’s theories of relativity were classical. but those are not Einstein’s only contributions to physics. Einstein essentially developed the first way to evidence that light is a particle through the photoelectric effect, which is what he won the Nobel prize for. Einstein developed our most accurate classical theory of physic with respect to some topics, but also was very present in the early development of quantum mechanics. He certainly had issues on a philosophical level concerning the probabilistic nature of the theory, but he did not have a problem with its correctness of it for the evidence that was available. He just believed that there was some mechanism behind the scenes that drove it, and so that is what lead him to work with some colleagues to come up with the EPR paradox, but that paradox turned out to be the nature of reality (essentially they came up with the concept of entanglement).

That said, equating Einstein to Coltrane is a reaching analogy. Music, and particularly what we see here in this picture, is certainly mathematics, but it is an entirely different type and application compared to physics, as well as orders of magnitude difference in complexity. That’s not to diminish the impactful nature of music, as the transcendental effect of music on a person was well appreciated by Einstein, but being able to describe galaxies is something else to that.

Thats probability. The fact that there is no such thing as gravity. Only a theory. Theory is not fact . Coltrane liked his flats . His density kept him in check . Jazzzzzzzzzzz

That music has a huge mathematical content is well-known to musicologists. That physics (including theories of relativity) has a huge mathematical content is also well-known. But to bring up Einstein in this discussion about Coltrane’s articulation of the circle of music is, IMO, silly.

1967: Death. Coltrane died of liver cancer at the age of 40 on July 17, 1967 at Huntington Hospital in Long Island. His funeral was held four days later at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in New York City.

Music and math have always been related, there is no doubt of that. I’m not saying that quadratic equations will make you a better player, but they both have patterns that relate to each other. However, I will take this a step further. Musicians and data processing geeks have much in common. I am both. I’m not talking about using windows, but actually writing hard core code. Music and data processing are linked together. What is music but two basic elements .….. pitch (high or low) and duration (how long the pitch is held). Data processing in it’s most elemental form is an electronic switch that is either turned on or off, 1 or 0. The combinations of either is virtually endless. Any player that can improvise in a given form, whether baroque, classical, romantic, or jazz should be able to write the wildest code imaginable, and vice versa, because they all operate on the same principles. When I went to school for music, an astonishing amount of graduates wound up writing code.

@Dean,thank you for your observation. I was ready to look up, Quantum Theory, Gravity, and Mechanics, to see if I missed something! Lol! I also didn’t see gravity mentioned. Just Theory..I am no physicist or scientist, I thought they were are different actions. Well perhaps I will share my efforts with this thread. Have a Quantum day!😝😜😊

that which is greater than thou… are you kidding … god is vague by concept…

Thank you!I much appreciate. And I totally agree with you.😘 🌹

Synesthesia,indeed. I know a bit about this. 😘

Coltrane

Genius who could open his heart and pour out truths that could connect with us

Completely

Was a genius

I love listening to him while I paint

this is simply the circle of 5ths

every guitar player should know this

1) John Coltrane, (not Coltrain).

2) Physics is crucial and wonderful, and I have taken to using my Ewart Sonic Spinning Tops to acquaint and illustrate certain aspects of physics and math to students, teachers, others and me, as I endeavor to get more people, especially the young people interested in all the sciences. and particularly physics, botany, and biology.

That being said, it is important to study all of these aspects and systems of information. However, music is bigger than and more complex than physics and math. Physics and math are elements of music. Music is far more complex than physics and math as we are yet to figure it out, and I am not just talking theory or science as we know it/them. Music is spiritual, emotional, art, science, craft, feeling, hearing, tasting, intuition, intellect, structure and more. We are yet to figure out all the music’s applications and so on. Knowing musical theory is important to those that are inquisitive and are interested in the logic, science, and developing a musical reservoir of resources, and obtaining a handle on the multitudinous nature of music. However, knowing all the theory in the world…math and physics won’t necessarily make you a good or even interesting music maker that is how complex and yet simple music is!

Our music has been World Music for a long time, especially when one considers the interaction that took place in the Carribean and Latin America (the Americas) with the indigenous peoples, Africans, indentured servants from India, China, the Middle East, and European peoples and cultures in the Western Hemisphere.

Baba Scott Joplin, Baba Jelly Roll Morton, Baba Yusef Lateef, and others before and after them placed a new spotlight and magnification lens on the notion and concept of World Music.

Thanks to all the writers, bloggers and those involved in this vital discourse.

Peace and Respect!

Douglas

All paths.. it’s spiritual not “religious”… It’s gratitude to the love supreme. The liner notes by train in the open sleeve are about love and a supreme that transcends any religious classification. It’s short sighted to see it must be classified to one particular faith. Quite frankly it’s childish. It’s far deeper as I believe Trane would agree.

The Nobel Prize in Physics 1921 was awarded to Albert Einstein “for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.” I don’t think this has anything to do with Quantum Theory. As far as I remember, this was a biggy later in the invention of TV?

FANTASTIC, but does it make your rear end move? I remember some wise words: “A well-shaken butt is worth more than all the genius in the cosmos.”

That was the first thing I noticed. Calling it “Einstein’s quantum theory” is an immediate red flag. It is common to throw around certain names (Einstein, Hawking, Galileo, etc) to support ideas that sound “revolutionary” but have little or nothing to do with (even an understanding of) these people’s work. Study the thinkers, don’t hijack them.

To Brad Lee:

Please don’t confuse (scientific) Theory with the conventional use of the word. That is playing word games as a shortcut to making a legitimate point and only serves to perpetuate ignorance and misunderstanding. The equivalent term for what you are stating is “hypothesis”, and we do NOT refer to a “hypothesis of gravity”. Theory, when referring to something like “Theory of Gravity” does essentially mean “established fact”. It’s the working explanation, like the instructions for operating your phone could be called “the Theory of (specific model) Phone Operation”.

it is incredible how many ignorants are commenting here just trying to look smart.

Raul, that comment is in itself a ‘know-it-all’ statement and with nothing behind it it also crosses ignorance. The statement, not you.

‘worth more’ is the key term there…

to Guiseppe.

Frankie DiDonato says:

June 26, 2019 at 10:13 am

All paths.. it’s spiritual not “religious”… It’s gratitude to the love supreme. The liner notes by train in the open sleeve are about love and a supreme that transcends any religious classification. It’s short sighted to see it must be classified to one particular faith. Quite frankly it’s childish. It’s far deeper as I believe Trane would agree.

I’m not Trane but I agree!!!

The Coltrane Circle diagram has an error, if consistency was intended. On the left-hand side the A in the inner circle should be linked with the B flat in the outer circle, and the G in the inner circle should not be linked with the G sharp in the outer circle.

Assuming this correction has been made, the outer circle depicts 5 sequences of notes with equal intervals of a tone, each starting on C, ascending clockwise and descending anti-clockwise. The inner circle also depicts 5 similar sequences but made up of the alternate notes. These sequences of notes, played on an instrument or sung, starting on any note, are known as “Auxiliary Augmented” or “Whole Tone” scales.

The inner and outer circles are linked with what I shall refer to as a “bridge”, moving both clockwise and anti-clockwise, at every second note of the above described “whole tone” sequences.

If a musician begins playing a sequence of notes, for example, at the No.1 C note and plays a clockwise sequence of notes crossing from outer to inner circle and back from inner to outer circle at each bridge, (a regular sequence of repeating patterns of intervals of semi-tone, tone, tone, semi-tone, tone, tone, etc.) i.e. a sequence of 36 notes consisting of C, C sharp, E flat, F, F sharp, A flat, B flat, B, C sharp, E flat, E, F sharp, A flat, A, B, D flat, D, E, G flat, G, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, G sharp, B flat, C, D, E flat, F, G, A flat, B flat, C, the sequence (or extended scale) includes every note of the chromatic scale, each played three times, takes six octaves to resolve before the pattern repeats, and, due to the arrangement of semi-tones and tones, sounds somewhat melodic rather than chromatic.

The outcome is the same no matter which note is used as a starting point, whether ascending or descending, and there is always choice whether or not to begin a sequence with a tone or a semi-tone, provided the pattern is maintained.

Fully chromatic music is to all intents and purposes “key-less”, i.e. “free”.

Musical keys are defined by dominant seventh chords. (Each key has only one dominant seventh chord.) If a sequence of chords (as in jazz blues) are all dominant seventh or altered dominant seventh chords, the chordal foundation of the music is in as many keys as there are chords, in other words it approaches being key-less the more different chords there are and it becomes key-less when all twelve dominant seventh based chords are employed.

The note sequences depicted in the corrected Coltrane Circle represent, in a sense, total freedom in music without losing melodic quality.

Genius!

Nice observations.

Please see my observations (July 5th 2019).

Kind regards,

I love Trane’s music but hate math.

Is it possible he was expressing a musical representation of a star? I haven’t heard anybody talk about the star. Love this thread!

It’s a pentagram. Which is the heart of magic. When you get bored of playing music you start to use your learning-capabilities to study other subjects. I heard that Charlie Parker was also very intellectual and read tons of books.

This diagram reminds me of Vortex math, and Nicola Tesla’s “Map to multiplication.”

https://sacredwai.com/about-us/vortex-math/

https://www.c‑ville.com/hitting-the-right-note-jazz-legend-roland-wiggins-reflects-on-a-lifetime-of-musical-expression/?fbclid=IwAR3C2ENVtXzpxOHtbez-dsCe68Uw_lb0zPTjyoq943piy_uKLvy_3eO-kG4

I noticed the whole tone sequence being suspended by the half tones (Half Steps.), much like what fourths regularly do!

Quantum Theory does not, as yet, handshake with Theory of Relativity! See author Mark Seifer, a theoretical physicist.

I believe there is no room for hatred in a world of truth. There is no life without death, so to speak!

Perhaps I could say: You may be opening the door for hatred to enter the world of actual proof. I don’ believe

Coltrane/Einstein harbered any hatred in their basic mindset.

At the end Einstein’s EGO waste soooo much time for unnecessary things! Instead working together with Bohr.…

INNER VIBES :: I’ve been studying this wheel, this circle for maybe 50 years now… I get the concept but playing the concept is another world… deep bow to John Coltrane! …and now, about that double diminished scale…

I like your style.

Thank you for your information and for NOT being one of those know-it-all people. It’s beautiful work.

This is the symbol for the observed rhythm of Venus from earth. Every eight years venus retrogrades in one of five constellations, creating the shape of a pentagram in the heavens. In ancient and modern astrology Venus is associated with music. Vettius Valens writes of Venus, “She makes…refined arts, pleasant sounds, music making, sweet singing…both inventors and also masters of these (professions).”

You mean circle yes?