We live in an era of genre. Browse through TV shows of the last decade to see what I mean: Horror, sci-fi, fantasy, superheroes, futuristic dystopias…. Take a casual glance at the burgeoning global film franchises or merchandising empires. Where in earlier decades, horror and fantasy inhabited the teenage domain of B‑movies and comic books, they’ve now become dominant forms of popular narrative for adults. Telling the story of how this came about might involve the kind of lengthy sociological analysis on which people stake academic careers. And finding a convenient beginning for that story wouldn’t be easy.

Do we start with The Castle of Otranto, the first Gothic novel, which opened the door for such books as Dracula and Frankenstein? Or do we open with Edgar Allan Poe, whose macabre short stories and poems captivated the public’s imagination and inspired a million imitators? Maybe. But if we really want to know when the most populist, mass-market horror and fantasy began—the kind that inspired television shows from the Twilight Zone to the X‑Files to Supernatural to The Walking Dead—we need to start with H.P. Lovecraft, and with the pulpy magazine that published his bizarre stories, Weird Tales.

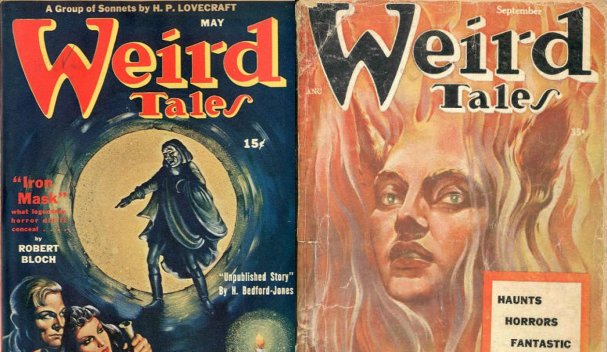

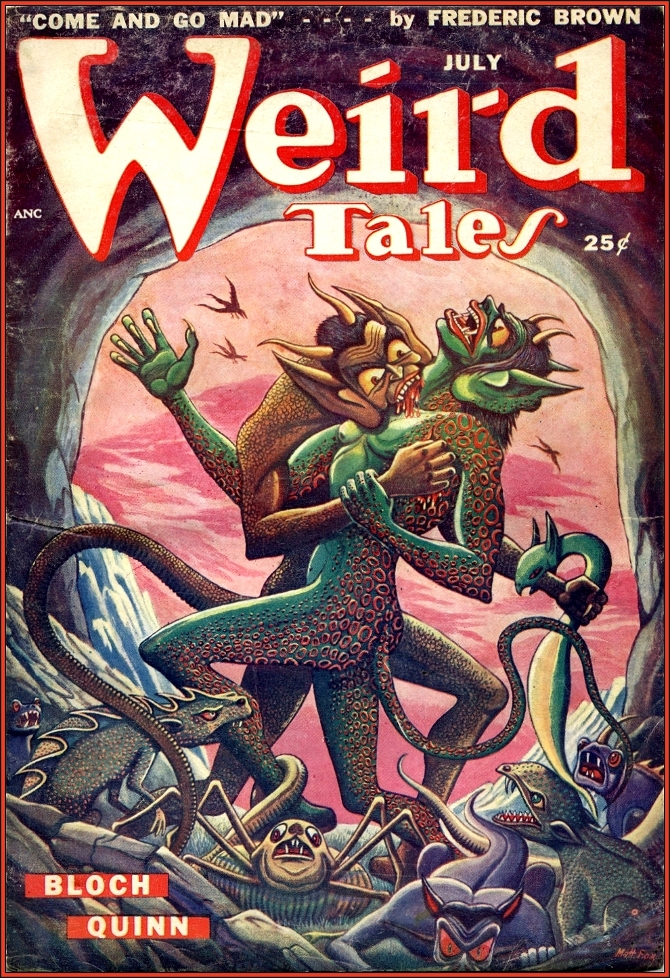

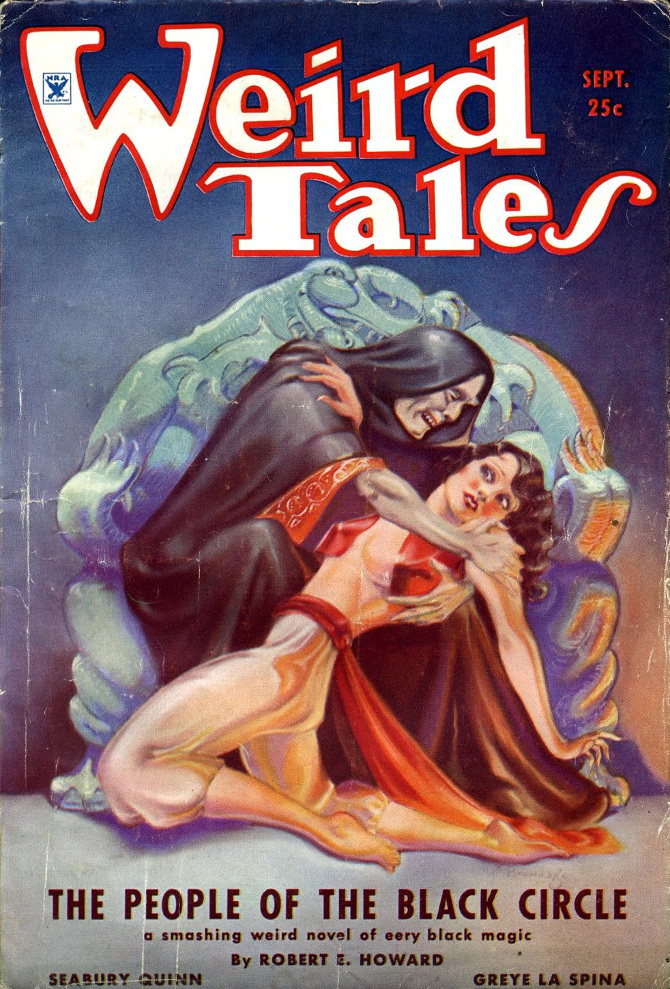

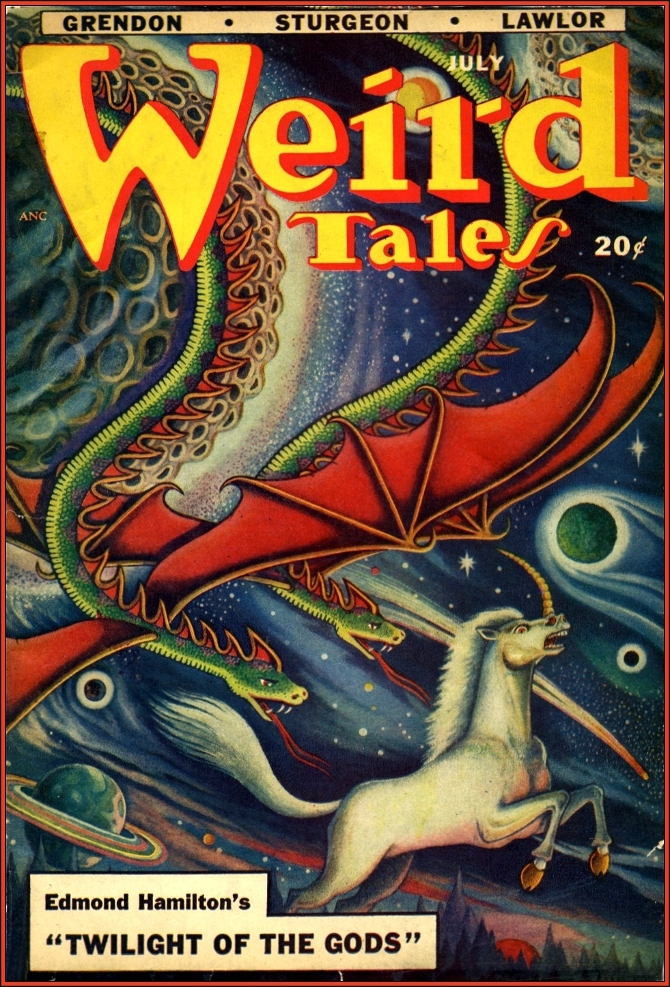

Debuting in 1923, Weird Tales, writes The Pulp Magazines Project, provided “a venue for fiction, poetry and non-fiction on topics ranging from ghost stories to alien invasions to the occult.” The magazine introduced its readers to past masters like Poe, Bram Stoker, and H.G. Wells, and to the latest weirdness from Lovecraft and contemporaries like August Derleth, Ashton Smith, Catherine L. Moore, Robert Bloch, and Robert E. Howard (creator of Conan the Barbarian).

In the magazine’s first few decades, you wouldn’t have thought it very influential. Founder Jacob Clark Hennenberger struggled to turn a profit, and the magazine “never had a large circulation.” But no magazine is perhaps better representative of the explosion of pulp genre fiction that swept through the early twentieth century and eventually gave birth to the juggernauts of Marvel and DC.

Weird Tales is widely accepted by cultural historians as “the first pulp magazine to specialize in supernatural and occult fiction,” points out The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (though, as we noted before, an obscure German title, Der Orchideengarten, technically got there earlier). And while the magazine may not have been widely popular, as the Velvet Underground was to the rapid spread of various subgenera of rock in the seventies, so was Weird Tales to horror and fantasy fandom. Everyone who read it either started their own magazine or fanclub, or began writing their own “weird fiction”—Lovecraft’s term for the kind of supernatural horror he churned out for several decades.

Fans of Lovecraft can read and download scans of his stories and letters to the editor published in Weird Tales at the links below, brought to us by The Lovecraft eZine (via SFFaudio).

Letter to the editor of Weird Tales, September 1923 – September 1923

Letter to the editor of Weird Tales, October 1923 – October 1923

Letter to the editor of Weird Tales, January 1924 – January 1924

Letter to the editor of Weird Tales, March 1924 – March 1924

Imprisoned With The Pharaohs – May/June/July 1924

Hypnos – May/June/July 1924

The Tomb – January 1926

The Terrible Old Man – August 1926

Yule Horror – December 1926

The White Ship – March 1927

Letter to the editor of Weird Tales, February 1928 – February 1928

The Dunwich Horror – April 1929

The Tree – August 1938

Fungi From Yuggoth Part XIII: The Port – September 1946

Fungi From Yuggoth Part X: The Pigeon-Flyers – January 1947

Fungi From Yuggoth Part XXVI: The Familiars – January 1947

The City – July 1950

Hallowe’en In A Suburb – September 1952

Fans of early pulp horror and fantasy—–or grad students writing their thesis on the evolution of genre fiction—can view and download dozens of issues of Weird Tales, from the 20s to the 50s, at the links below:

The Internet Archive has digitized copies from the 1920s and 1930s.

The Pulp Magazine Project hosts HTML, FlipBook, and PDF versions of Weird Tales issues from 1936 to 1939

This site has PDF scans of individual Weird Tales stories from the 40s and 50s, including work by Lovecraft, Ray Bradbury, Dorothy Quick, Robert Bloch, and Theodor Sturgeon.

And to learn much more about the history of the magazine, you may wish to beg, borrow, or steal a copy of the pricy collection of essays, The Unique Legacy of Weird Tales: The Evolution of Modern Fantasy and Horror.

Related Content:

Download 15,000+ Free Golden Age Comics from the Digital Comic Museum

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness