?si=RFbzFSzSNWzua3‑7

Could you use a mental escape? Maybe a trip to Mars will do the trick. Above, you can find high definition footage captured by NASA’s three Mars rovers–Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity. The footage (also contributed by JPL-Caltech, MSSS, Cornell University and ASU) was stitched together by ElderFox Documentaries, creating what they call the most lifelike experience of being on Mars. Adding more context, Elder Fox notes:

The footage, captured directly by NASA’s Mars rovers — Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity, and Perseverance — unveils the red planet’s intricate details. These rovers, acting as robotic geologists, have traversed varied terrains, from ancient lake beds to towering mountains, uncovering Mars’ complex geological history.

As viewers enjoy these images, they will notice informal place names assigned by NASA’s team, providing context to the Martian features observed. Each rover’s unique journey is highlighted, showcasing their contributions to Martian exploration.

Safe travels.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

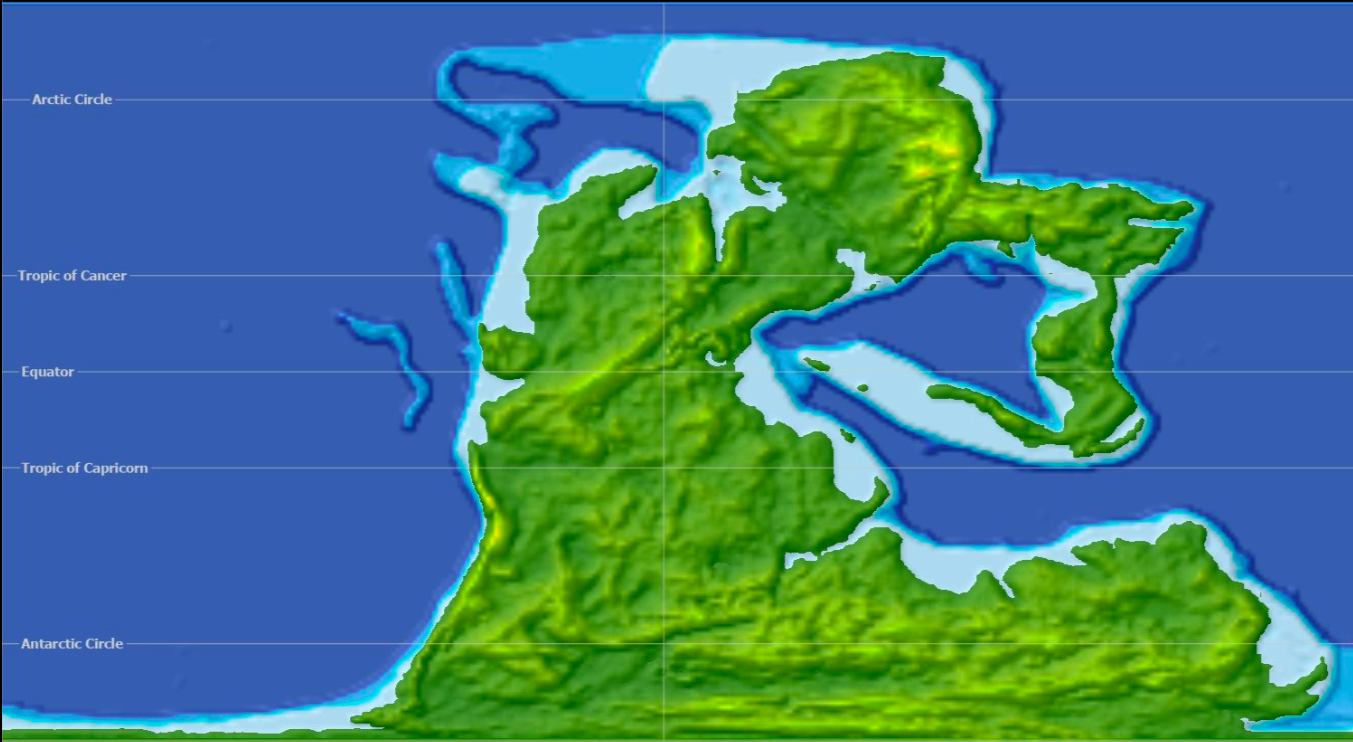

Behold Colorful Geologic Maps of Mars Released by The United States Geological Survey

Carl Sagan Presents Six Lectures on Earth, Mars & Our Solar System … For Kids (1977)

Hear the Very First Sounds Ever Recorded on Mars, Courtesy of NASA