“I’ve been a painter all my life. I’ve been a musician most of my life. If you can paint with a brush, you can paint with words.” — Joni Mitchell

There’s been a lot of love for Joni Mitchell circulating of late, the sort of heartfelt outpouring that typically accompanies news of an artist’s death.

Fortunately, the beloved singer-songwriter has shown herself to be very much alive, despite a 2015 brain aneurysm that initially left her unable to speak, walk, or play music.

As she quipped in a recent interview with Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden, “I’m hard to discourage and hard to kill.”

How wonderful, then to be so fully alive as a windfall of testimonials roll in, describing the personal significance of her work, from the famous friends feting her last month with a concert of her own compositions as she was awarded the Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song to ordinary citizens with fond memories of singing “The Circle Game” at camp.

Mitchell says that song, which you can hear her singing above, along with last month’s all-star line up, “kind of became like Old MacDonald Had a Farm” owing to its campfire popularity, though she resisted Hayden’s invitation to explain its timeless appeal:

I don’t know. Why was Old MacDonald Had a Farm so timeless?

This 79-year-old legend’s growing tendency to goof her way through interviews is endearing, but the Gershwin Prize is serious business, intended to “celebrate the work of an artist whose career reflects the influence, impact and achievement in promoting song as a vehicle of musical expression and cultural understanding.”

Performer Cyndi Lauper reflected that Mitchell’s influence is not confined to the realm of music:

When I was growing up the landscape of music was mostly men. There were a few women — far and few from me — and Joni Mitchell was the first artist who really spoke about what it was like to be a woman navigating in a male world … You taught me that I could be a multimedia artist if I wanted, because you painted and you wrote and you played and that’s what I wanted and I thought, “Well, if you could do it, maybe I can do it too.”

Mitchell trained as a commercial artist. Her paintings and self-portraits are featured on the covers of seventeen albums. When Hayden asked whether she primarily conceives of herself as a musician or artist, Mitchell went with artist, “because it’s more general.”

I think that, you know, my songs are kind of, they’re not folk music, they’re not chat. They’re kind of art songs and they embody classical things and jazzy things and folky things, you know, long line poetry. So yeah, I forged my identity very early as an artist. I’ve always thought of myself as an artist, but not specifically as a musician. You know, in some ways I’m just not a normal musician because I play in open tunings. I never learned the neck of my guitar well enough to jam with other people. I can jam if I lead, but I can’t really follow.

She believes her painting practice enriches her songwriting, much as crop rotation helps a field to remain fertile.

Not every artist switches lanes so effortlessly.

When Georgia O’Keeffe — who once told ARTnews she’d choose to be reincarnated as a “blond soprano who could sing high, clear notes without fear” — confided that she would have liked to be a musician as well as an artist, “but you can’t do both”, Mitchell claims to have responded, “Yeah, you can. You just have to give up TV.”

Songwriters George and Ira Gershwin, namesakes of the Prize for Popular Song, were closer to Mitchell in terms of creative omnivorousness. Their self-portraits hang in the National Portrait Gallery and the Library of Congress’ Gershwin room.

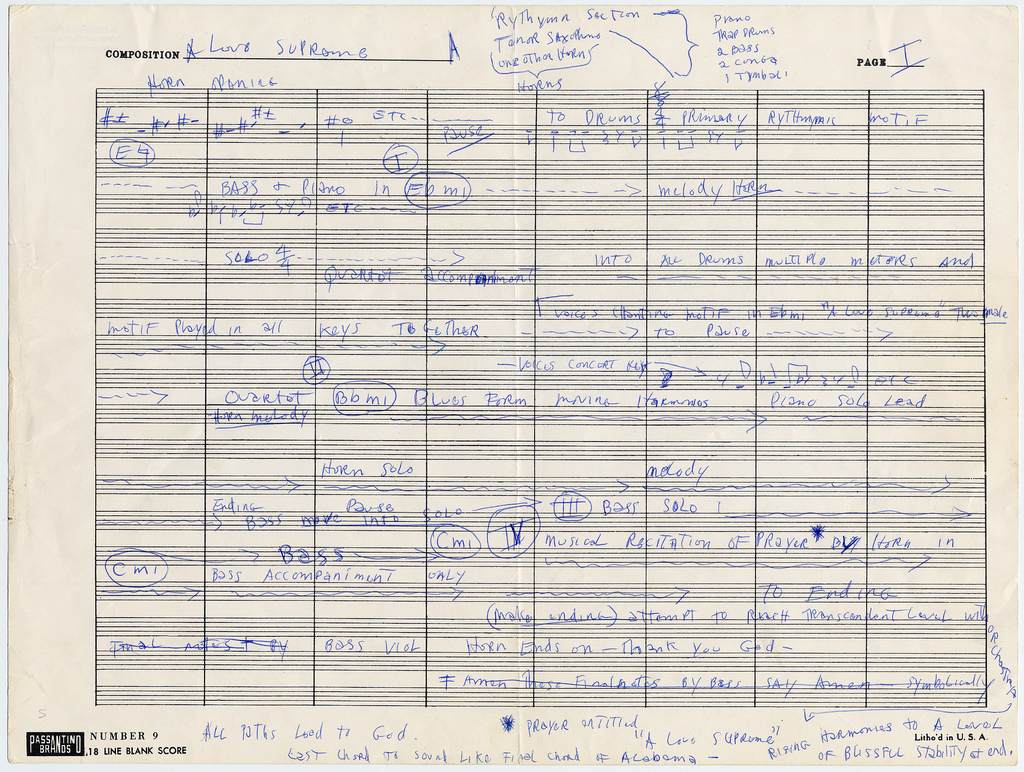

Mitchell was thrilled when Library staff presented her with a copy of the handwritten original score for her favorite George Gershwin tune, “Summertime,” which she recorded for Herbie Hancock’s 1998 album, Gershwin’s World, seven years after an Interview magazine piece in which she referred to her voice as “middle-aged now…like an old cello.”

Twenty-five years later, singing “Summertime” at the end of the concert in her honor, that cello’s tones are seasoned…and even more mellow.

I love the melody of (Summertime) and I like the simplicity of it. And I don’t know, I just I really get a kick out of singing it.

Stream Joni Mitchell: The Library of Congress Gershwin Prize, an all-star concert featuring Brandi Carlile, Annie Lennox, James Taylor, Herbie Hancock, Cyndi Lauper, and other luminaries, including the Lady of the Canyon herself, for free on PBS through April 28.

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.