Europe at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth: what a time and place to be alive. Or rather, what a time and place to be alive for people in the right countries and, more importantly, of the right classes, those who saw a new world taking shape around them and partook of it with all possible heartiness. The period between the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914, best known by its French name La Belle Époque, saw not just peace in Europe and empires at their zenith, but all manner of technological, social, and cultural innovations at home as well.

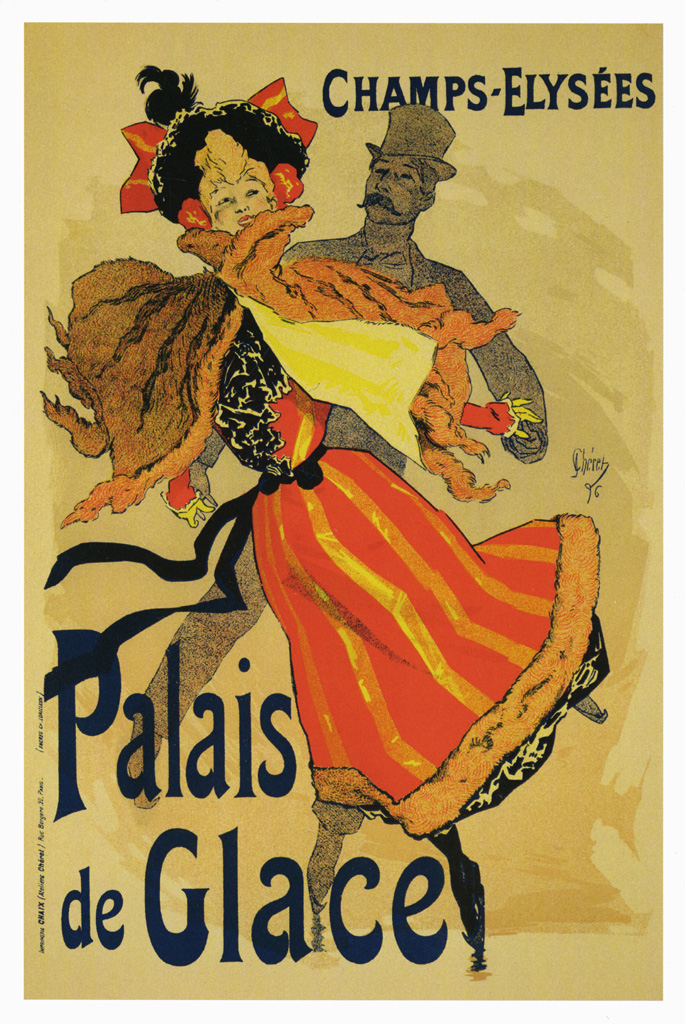

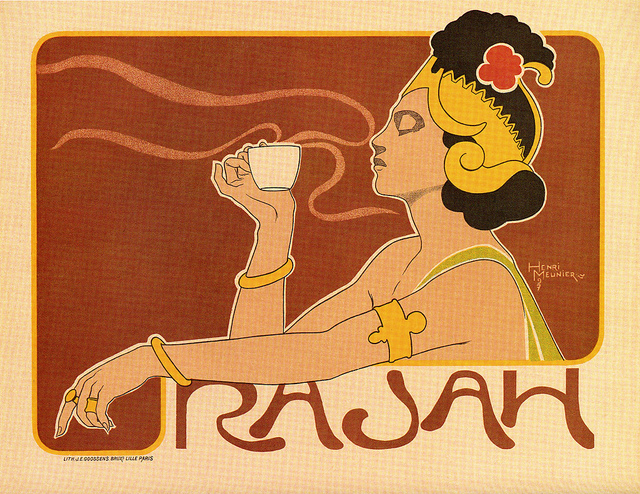

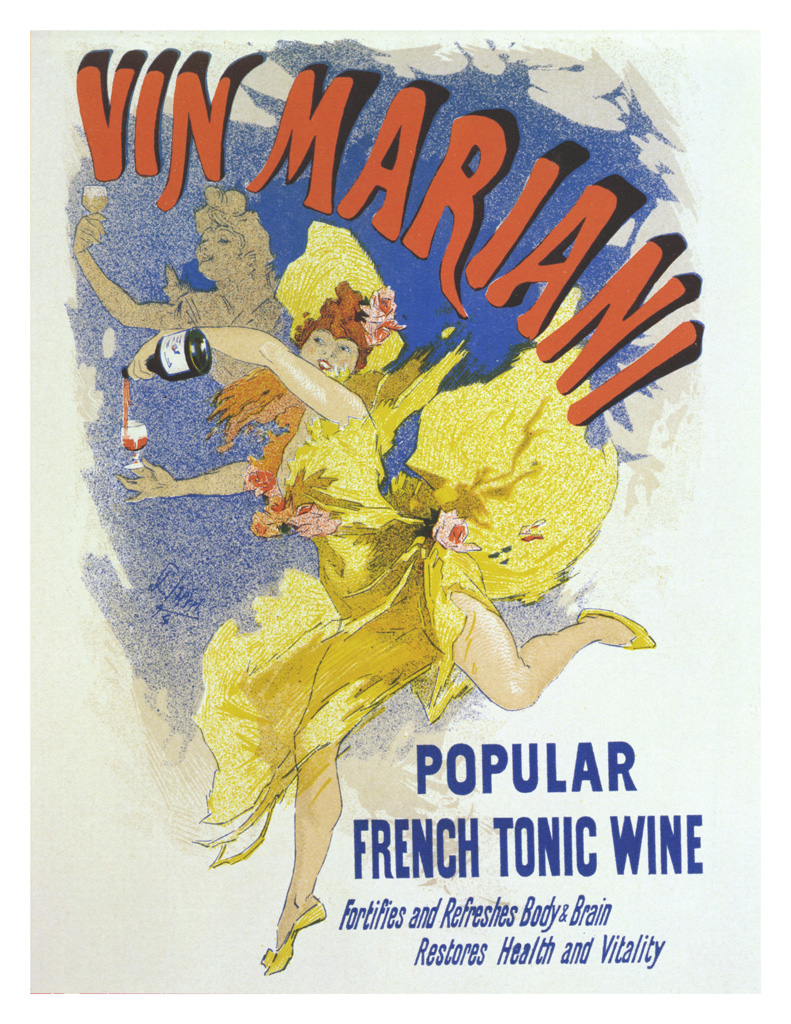

We here in the 21st century have few ways of tasting the life of that time as rich as its posters, more than 200 of which you can view in high resolution and download from the “Art of the Poster 1880–1918,” a Flickr collection assembled by the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.

“In the late nineteenth century, lithographers began to use mass-produced zinc plates rather than stones in their printing process,” says the accompanying text. “This innovation allowed them to prepare multiple plates, each with a different color ink, and to print these with close registration on the same sheet of paper. Posters in a range of colors and variety of sizes could now be produced quickly, at modest cost.”

Like other of the most fruitful technological advancements of the era, this leap forward in poster-printing drew the attention, and soon the efforts, of artists: well-regarded illustrators and graphic designers like Alphonse Mucha, Jules Chéret, Eugène Grasset, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec took to the new method, and “The ‘Golden Age of the Poster’ was the spectacular result.”

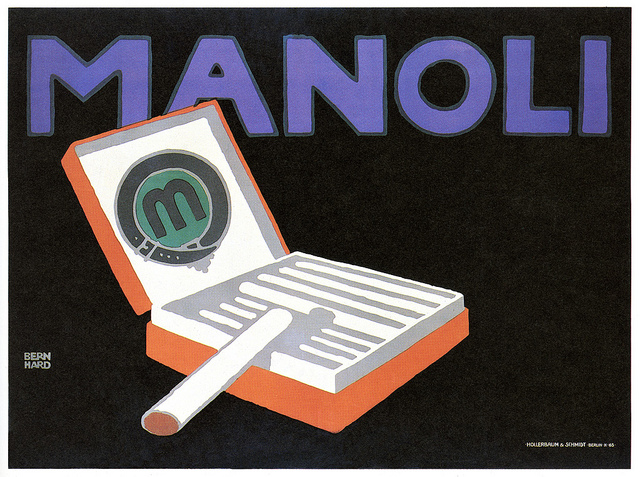

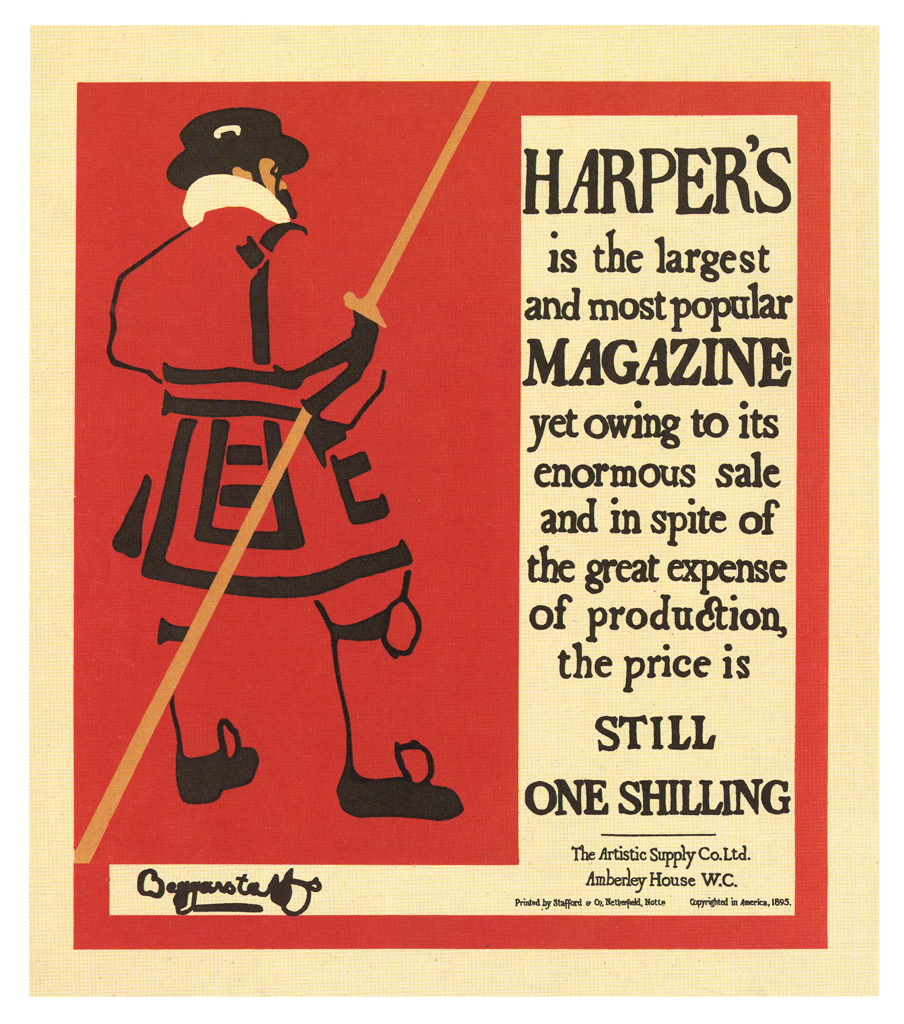

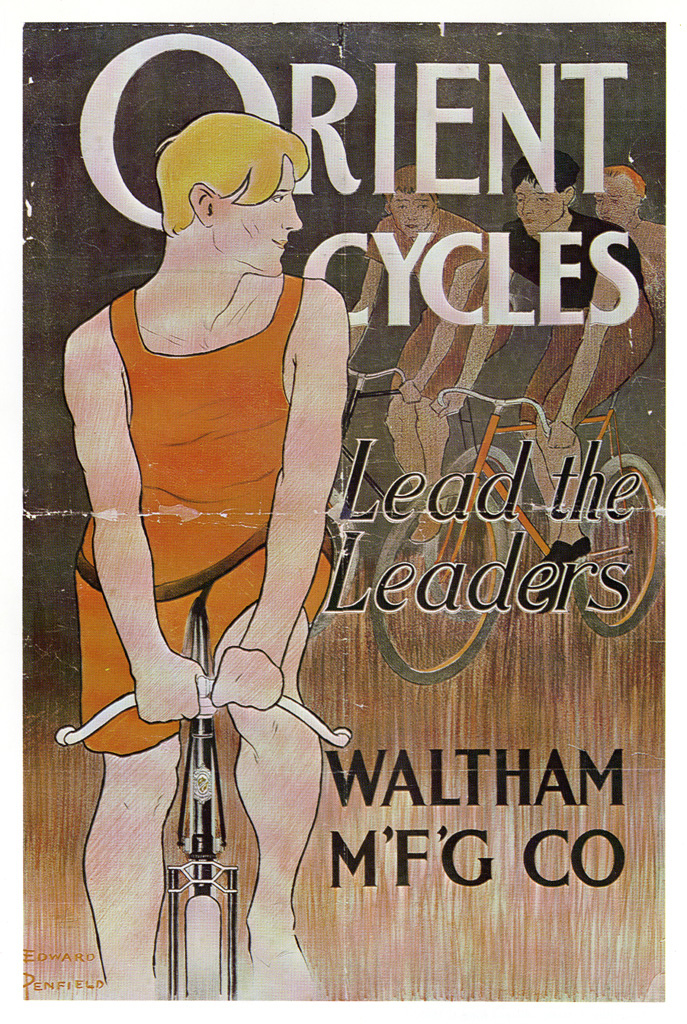

While many of the best-remembered posters of that Golden Age come from France, it touched the streets of every major city in western Europe as well as those of England and America, all places whose well-heeled populations found themselves newly and avidly interested in art, photography, motion pictures, magazines, bicycles, automobiles, absinthe, coffee, cigarettes, and world travel.

The companies behind all those exciting things had, of course, to advertise, but unlike in earlier times, they couldn’t settle for getting the word out; they had to use images, and the most vivid ones possible at that. They had to use them in such a way as to associate what they had to offer with the abundant spirit of the time, whether they called that time La Belle Époque, the Wilhelmine period, the late Victorian and Edwardian era, or the Gilded Age.

All those names, of course, were applied only in retrospect, after it became clear how bad times could get in the twentieth century. But then, none of us ever realize we’re living through a golden age before it comes to its inevitable end; until that time, best just to enjoy it. You can enter the poster archive here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017.

Related Content:

René Magritte’s Early Art Deco Advertising Posters, 1924–1927