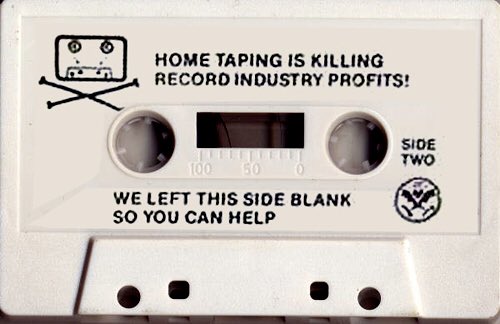

The first time I saw the infamous Skullcassette-and-Bones logo was on holiday in the UK and purchased the very un-punky Chariots of Fire soundtrack. It was on the inner sleeve. “Home Taping Is Killing Music” it proclaimed. It was? I asked myself. “And it’s illegal” a subhead added. It is? I also asked myself. (Ironically, this was a few months before I came into possession of my first combination turntable-cassette deck.)

Ten years and racks and racks of homemade cassette dubs on my shelves later, music seemed to be doing very well. (Later, by going digital, the music industry killed itself, and I had absolutely nothing to do with it.)

British record collectors will no doubt remember this campaign that started in 1981, another business-backed “moral” panic. And funnily enough it had nothing to do with dubbing vinyl.

Instead, the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) were taking aim at people who were recording songs off the radio instead of purchasing records. With the rise of the cassette tape in popularity, the BPI saw pounds and pence leaving their pockets.

Now, figuring out lost profits from home taping could be a fools’ errand, but let’s focus on the “illegal” part. Technically, this is true. Radio stations pay licensing fees to play music, so a consumer taping that song off the radio is infringing on the song’s copyright. Britain has very different “fair use” laws than America. In addition, digital radio and clearer signals have complicated matters over the years.

In practice, however, the whole thing was bunkum. Radio recordings are historic. Mixtapes are culture. I have my tapes of John Peel’s BBC shows, which I recorded for the music. Now, I listen to them for Peel’s intros and outros.

Seriously, the Napalm Death Peel Sessions *only* make sense with his commentary. Whoever taped this is an unknown legend:

The post-punk crowd knew the campaign was bunkum too. Malcolm McLaren, always the provocateur, released Bow Wow Wow’s cassette-only-single C‑30 C‑60 C‑90 Go with a blank B‑side that urged consumers to record their own music. EMI quickly dropped the band.

The Dead Kennedys also repeated the black b‑side gimmick with In God We Trust, Inc. (I would be interested in anybody who picks up a copy used of either to see what *is* on the b‑side).

And then there were the parodies. The metal group Venom used “Home Taping Is Killing Music; So Are Venom” on an album; Peter Principle offered “Home Taping Is Making Music”: Billy Bragg kept it Marxist: “Capitalism is killing music — pay no more than £4.99 for this record”. For the industry, music was the product; for the regular folks, music was communication, it was art, it was a language.

The campaign never did much damage. Attempts to levy a tax on blank cassettes didn’t get traction in the UK. And BPI’s director general John Deacon was frustrated that record companies didn’t want to splash the Jolly Roger on inner sleeves. The logo lives on, however, as part of torrent site Pirate Bay’s sails:

Just after the hysteria died down, compact discs began their rise, planting the seeds for the digital revolution, the mp3, file sharing, and now streaming.

(Wait, is it possible to record internet streams? Why, yes.)

If you have any stories about how you helped “kill music” by recording your favorite DJs, confess your crimes in the comments.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.