Robert Walser’s last novel, Der Räuber or The Robber, came out in 1972. Walser himself had died fifteen years earlier, having spent nearly three solid decades in a sanatorium. He’d been a fairly successful figure in the Berlin literary scene of the early twentieth century, but during his long institutionalization in his homeland of Switzerland — from which he refused to return to normal life, despite his outward appearance of mental health — he claimed to have put letters behind him. As J. M. Coetzee writes in the New York Review of Books, “Walser’s so-called madness, his lonely death, and the posthumously discovered cache of his secret writings were the pillars on which a legend of Walser as a scandalously neglected genius was erected.”

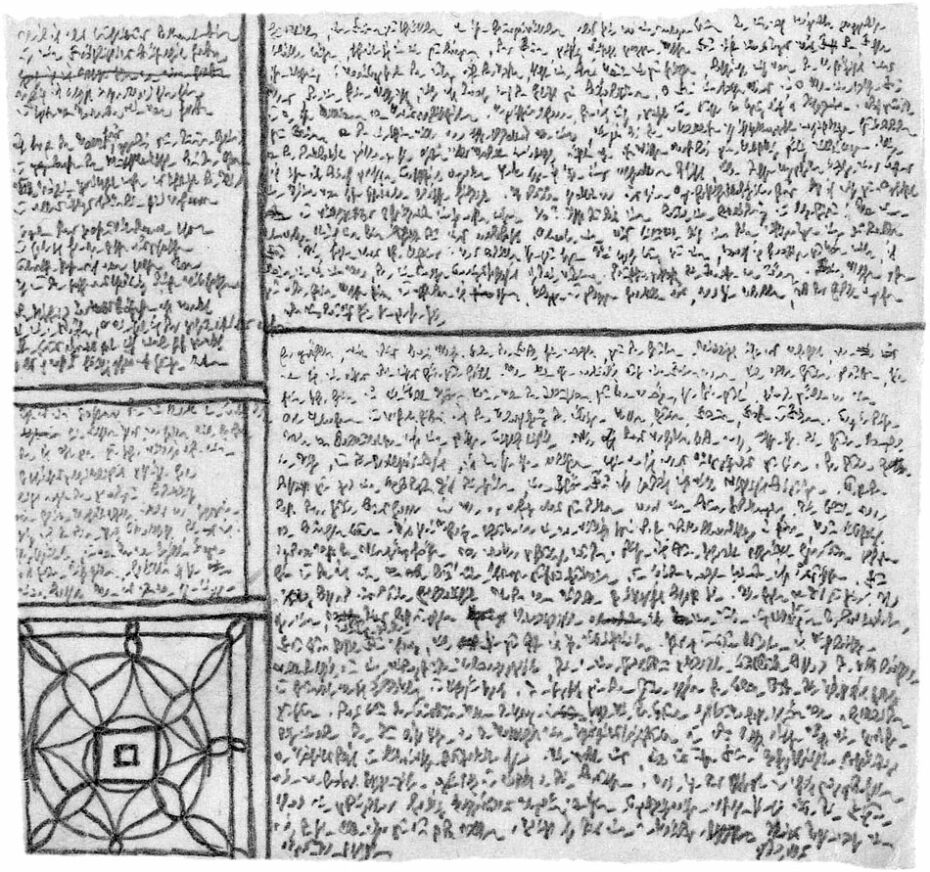

This cache consisted of “some five hundred sheets of paper covered in a microscopic pencil script so difficult to read that his executor at first took them to be a diary in secret code. In fact Walser had kept no diary. Nor is the script a code: it is simply handwriting with so many idiosyncratic abbreviations that, even for editors familiar with it, unambiguous decipherment is not always possible.”

He devised this extreme shorthand as a kind of cure for writer’s block: “In a 1927 letter to a Swiss editor, Walser claimed that his writing was overcome with ‘a swoon, a cramp, a stupor’ that was both ‘physical and mental’ and brought on by the use of a pen,” writes the New Yorker’s Deirdre Foley Mendelssohn. “Adopting his strange ‘pencil method’ enabled him to ‘play,’ to ‘scribble, fiddle about.’ ”

“Like an artist with a stick of charcoal between his fingers,” Coetzee writes, “Walser needed to get a steady, rhythmic hand movement going before he could slip into a frame of mind in which reverie, composition, and the flow of the writing tool became much the same thing.” This process facilitated the transfer of Walser’s thoughts straight to the page, with the result that his late works read — and have been belatedly recognized as reading — like no other literature produced in his time. As Brett Baker at Painter’s table sees it,” Walser’s compressed prose (rarely more than a page or two) constructs full narratives than can be consumed rapidly – nearly ‘at a glance,’ as it were. Their short length allows the reader to revisit the work in detail, focusing on sentences, phrases, or words as one might examine the painted passages or marks on a canvas.”

These ultra-compressed works from the Bleistiftgebiet, or “pencil zone,” writes Foley Mendelssohn, “establish Walser as a modernist of sorts: the recycling of materials can make the texts look like collages, modernist mashups toeing the line between mechanical and personal production.” But they also make him look like the forerunner of another, later variety of experimental literature: in a longer New Yorker piece on Walser, Benjamin Kunkel proposes 1972 as a culturally appropriate year to publish The Robber, “a fitting date for a beautiful, unsummarizable work every bit as self-reflexive as anything produced by the metafictionists of the sixties and seventies.” The publication of his “microscripts,” in German as well as in translation, has ensured him an influence on writers of the twenty-first century — and not just their choice of font size.

For anyone interested in seeing a published version of Walser’s writing, see the book Microscripts, which features full-color illustrations by artist Maira Kalman.

via Messy Nessy

Related content:

Discover Nüshu, a 19th-Century Chinese Writing System That Only Women Knew How to Write

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.